Wow! More than a year has passed since I’ve posted in this blog. So much has happened, some of which amounts to a veritable sea change in my life. But I’m not going to get into that here. Relevant for Stormhorn.com is this: the site’s URLs, which acquired an unwarranted and unwanted prefix when I was forced to switch from my superb but now defunct former webhost to Bluehost, are now fixed, and this blog is properly searchable and functional again.* Already, in just a couple days, I’ve seen three sales of my book The Giant Steps Scratchpad, and hopefully this site can once again gain some traction as both a jazz saxophone resource and a chronicle of my obsession with storm chasing.

As the dust began to settle from a painful but beneficial transition, I found myself with the wherewithal to finally chase a bit more productively and independently than I have in a long time. It felt wonderful—wonderful!—to hit the Great Plains again in a vehicle that is trustworthy, economical, and comfortable for driving long distances. Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota—hello, old friends. It was so good to see you again at last, such a gift to drive your highways and take in your far-reaching landscapes . . . and yes, to exult in your storms, your wild convection that transforms your skies into battlegrounds of formidable beauty.

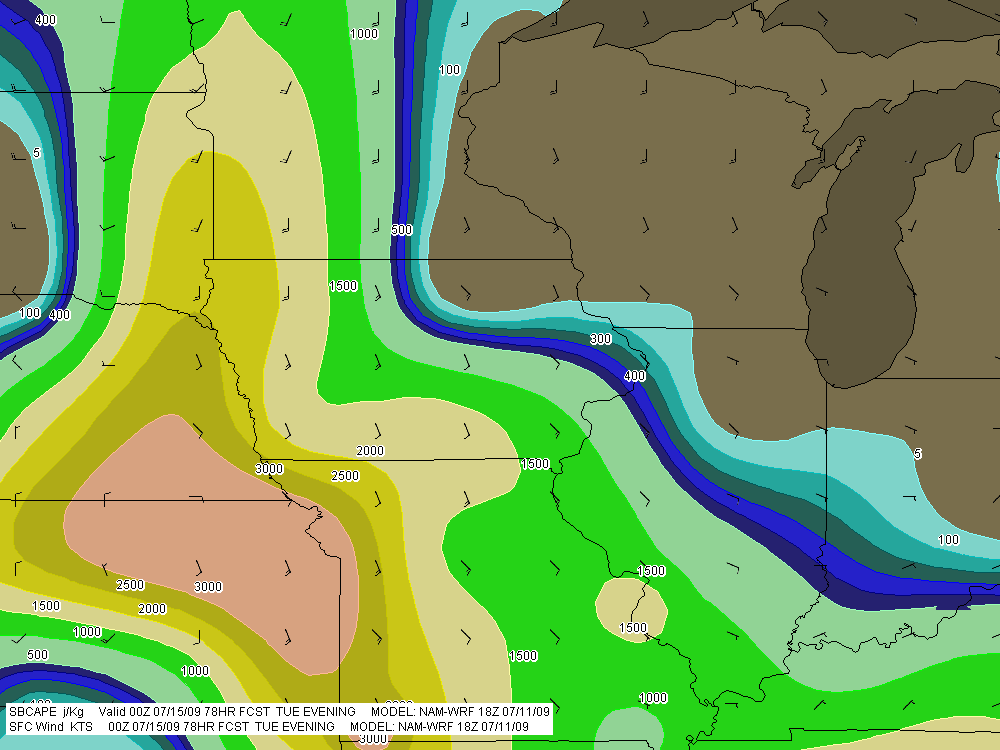

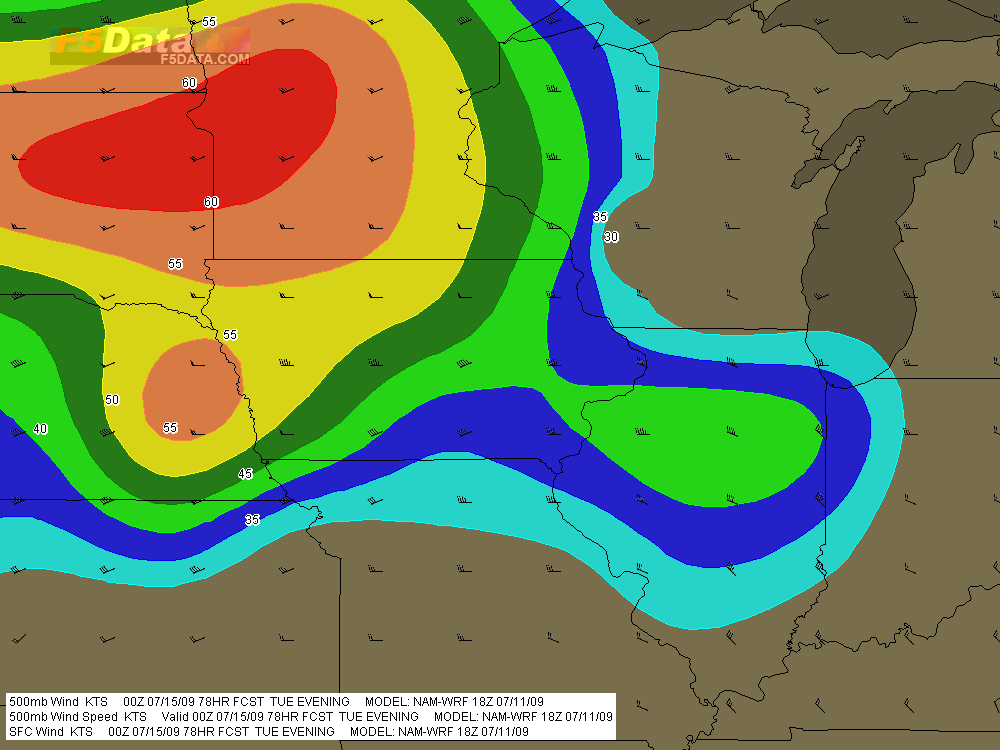

It is a long drive from Michigan to tornado alley, eight hundred miles or more just to get to the front door. Ironically, I could have spared myself most of my first trip. It landed me in Wichita overnight, then on to chase the next day in southwest Kansas and northeastward almost to Salina. No tornadoes, though. They were there, all right, but I was out of position and uninclined to punch through a bunch of high-precip, megahail crud along the warm front in order to intercept potent-looking (on the radar) but low-visibility mesocyclones. Two days later, though, on May 20 in northwest Indiana on my way back home, the warm front was exactly the place to be, and I filmed a small but beautiful tornado south of Wolcott. It was my one confirmed tornado of the year.

A few weeks later I hit the northern plains with my friend Jim Daniels, a retired meteorologist from Grand Junction, Colorado. It was his first chase, and for me, one of the blessings, besides the good fellowship and opportunity to build our new friendship, was introducing someone to chasing who already had his conceptual toolkit assembled. No need to explain how a thunderstorm works or how to interpret radar—Jim’s a pro; I just handed him my laptop, let him explore the tools, and we were ready to rumble.

Except—no tornadoes.

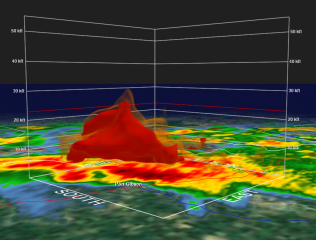

Then came August and a shot at severe weather right here in Michigan. I tagged along with a slow-moving, cyclic, lowtop supercell with classic features through the western thumb area of the state. It was nicely positioned as tail-end Charlie, sucking in the good energy unimpeded. A little more instability and it could have been a bruiser. As it was, it cycled down to the point where I thought it was toast, just a green blob on GR3, at which point, faced with a long drive home, I gave up the chase. Naturally the green blob powered back up and then spun up a weak twister ten or fifteen minutes later.

I didn’t mind missing the tornado. Well, not much. I had chased about fifty miles from Chesaning to south of Mayville, about two and a quarter hours, and gotten plenty of show for my money—rapidly rotating wall clouds, a funnel or two, and some really sweet structure of the kind you rarely see in Michigan. Then on the way back, as a cold front swept in, the sunset sky was spectacular.

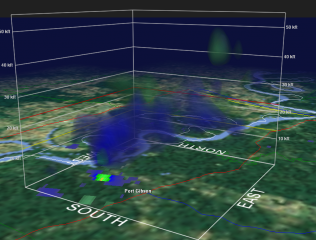

Waterspout season has also come and gone, and I hit the lakeshore a number of times. One of those times was fruitful, and I captured some images of a couple picturesque waterspouts out at Holland Beach. They were all the more interesting because they occurred southwest of a clearly defined mesocyclone. But I’ll save that and a pic or two for a different post. It deserves a more detailed account, don’t you agree?

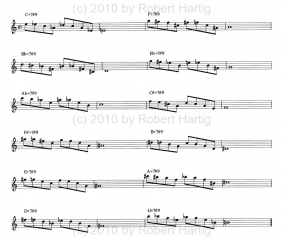

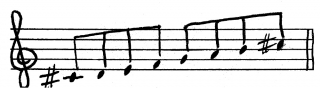

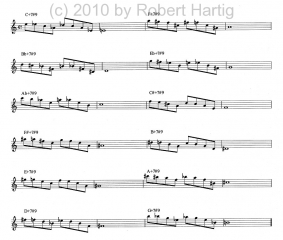

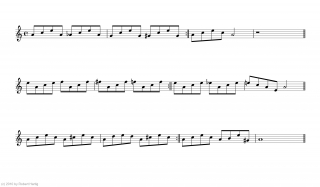

Stormhorn.com is about jazz saxophone and improvisation as well as storm chasing. So if jazz is your preferred topic, stay tuned. It’ll be comin’ at ya. Got a few patterns and licks to throw at you that I think you’ll enjoy.

That’s all for now. Stormhorn.com is back in the race.

____________________

* The one exception is the photo gallery. Photos in individual posts work fine, but the links on the photos page don’t work.

Also, formatting is messed up in the text of a lot of older posts. So I still have some issues to work through with BlueHost. I’ll probably have to pay to get the image gallery working right again; hopefully not so with the formatting stuff.