Today marked the turning point of sunset time.

Yesterday was the year’s earliest sunset; here in Hastings, Michigan, it occurred at thirty-eight seconds past 5:07. Henceforth, beginning this evening, sunset will occur later and later every day.

The change is incremental at first. Today the Sun set only a hair’s breadth later than yesterday. My sunrise/sunset chart still shows the same time, 5:07:38, but twilight lingered two seconds longer–hardly a noteworthy difference except that it’s the beginning of seasonal change. Meteorological winter is already underway; it began on December 1. Now we’re moving toward astronomical winter, and the changing of the guard has begun.

Winter solstice is still thirteen days away. On that date, December 21, the span between sunrise and sunset will be at its narrowest and daylight time at its shortest. But already the Sun will be setting later and later. On the 21st it will set at 5:11 in my town. However, until then it will also continue to rise later and in slightly broader increments, so that the gap between sunrise and sunset will keep narrowing from now till the 21st. After that, although the Sun will still rise earlier and earlier through January 2, it will do so by comparatively smaller increments, and the accelerating lateness of sunset time will begin to outstrip the braking lateness of the sunrise.

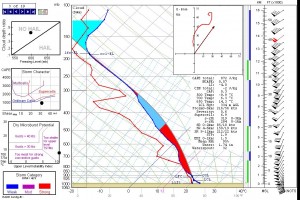

Sounds complicated, but it’s a simple concept, and if you saw it on a graph, you’d get it right away. In a nutshell, the days of the latest sunrise (January 2) and the earliest sunset (yesterday evening) are out of sync. December 21, winter solstice, is when those two times are closest; hence, it’s the “shortest day” of the year.