Right now my buddies are out west chasing this latest storm system. I’m not with them because I can’t afford it. Money has been extremely tight and what I take in has got to go toward paying the bills and putting food on the table for Lisa and me. That’s the reality of life. I’ve been on a couple of unproductive chases so far this year, and now that a decent system is finally in play out west, I’ve got to pass it up. I can’t even chase what promises to be a fabulous day today in Illinois. Once again I’ll be picking over the scraps later on here in Michigan. It’ll be nice to get some lightning, but it just isn’t the same.

Armchair chasers are typically regarded as off on the sidelines of storm chasing. But there’s a difference when you’ve been in the game and find yourself benched. You know what you’re missing. You’ve been looking forward to it all year with intense eagerness, like a kid looks forward to Christmas. So when you can’t do a thing about it unless it lands right in your lap–which in Michigan, land of cold fronts and veered surface winds, doesn’t happen often–it is extremely frustrating. SDS is one thing, but this is something else.

Armchair chasing? Nuts. I get to where I don’t even want to go near a radar. But I do anyway. I can’t seem to help myself. I want to see what’s happening with my friends, what storms they’re on. I look at the forecast models, too, hoping against hope that they’ll stop sticking their stupid tongues out at me and smile at me for once.

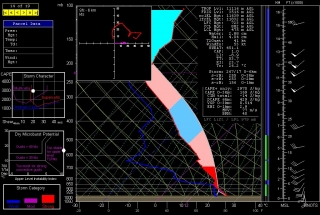

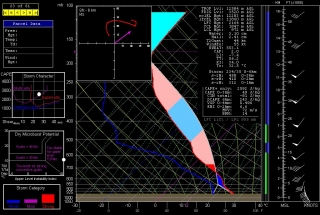

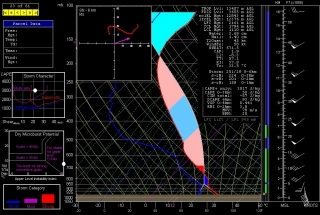

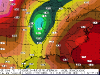

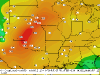

Today the RUC actually seems to do so. Here’s the 10Z KGRR sounding for 23Z this evening. Not bad. I just wish I believed that those surface winds and helicities were accurate, but I don’t, not with other models (NAM, GFS, and SREF) shouting them down. Besides, the HRRR composite reflectivity hates me. I can’t stand looking at it. Again, though, as with the radar, I do anyway. Storms progged to fire in northern Illinois and even south along the Michigan border…all I’d have to do is hop in my car, head west along I-80 and maybe down toward Peoria, or even just 80 miles south down US 131 toward the state line as a compensation prize, and I’d be in the sweet zone. But it ain’t gonna happen.

Rant, rant, rant. On this date last year I was on the most unforgettable chase of my life in northern South Dakota. Today, I wish this present system would just get on with it and get it over with so I can forget about weather, forget about the fact that I call myself a storm chaser when I’m not chasing storms. What a laugh. True, I’ll be chasing this evening locally for the first time for WOOD TV8. That I can at least afford, and it’s a nice way to work with the storms that we do get and possibly provide a bit of public service. But I don’t have high expectations. That’s a good thing here in populous West Michigan, but it doesn’t satisfy a convective jones. I just hope this season doesn’t drift into the summer pattern before I can get out and see at least one good tornadic supercell.

Okay, enough of this self-indulgent, babyish whining. I just had to get it out of my system, because in all seriousness, missing out on the action bothers me a lot, an awful lot, more than I can describe. It’s an absolutely miserable feeling. But it’s how things are, and life goes on.

Good luck out there in the Plains, Bill, Tom, and Mike–and Ben and Nick, though I know you guys are chasing separately. I hope you bag some great tornadoes today and over the next few days. As for me, it’s time to shower up, head to church, and remind myself that there’s more to life than this.