The SPC has placed Michigan and the Great Lakes in a slight risk area for tomorrow. But tornadoes aren’t in the picture. The summer pattern appears to be setting in, with the jet stream moving its headquarters to the US/Canadian border. As far as Michigan is concerned, that’s close enough that we can still expect some decent kinematics here and there. But what we get tends to result in linear MCSs more than supercells and the like.

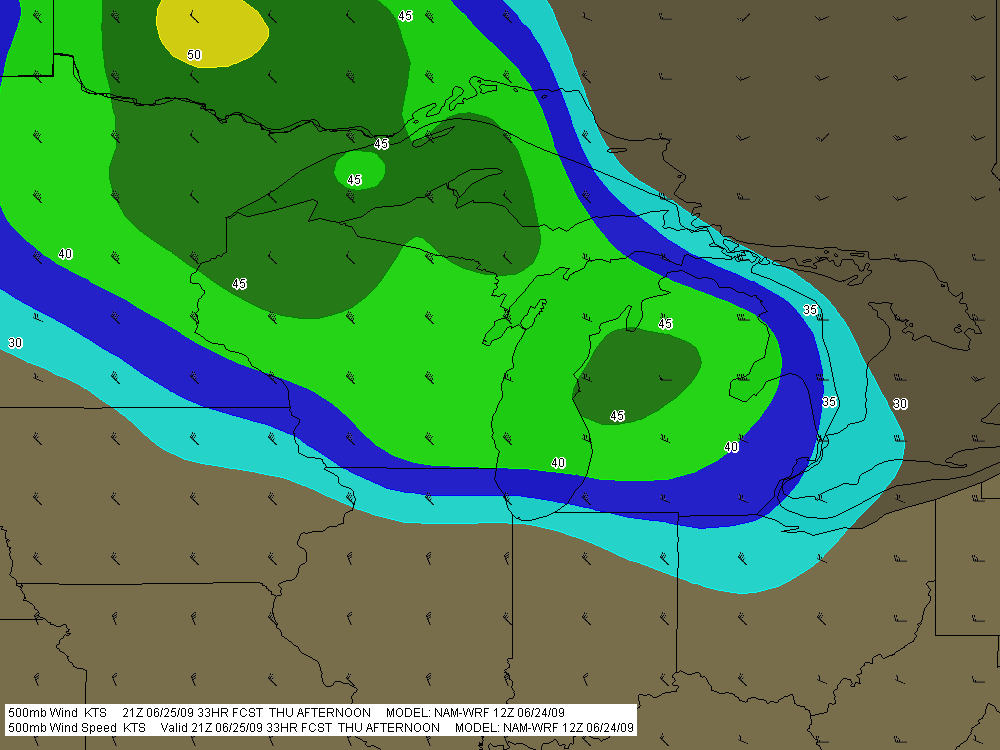

Tomorrow’s SBCAPE should settle in between 2,500 and 3,000 j/kg, with dewpoints in the 70s. That’s certainly an ample supply of convective fuel. And F5 Data shows this for H5 wind speeds at 21Z:

If you can live with northwest flow, that’s not bad. But of course, the underlying winds are all westerly. Once again, Michigan’s energy will get sabotaged by unidirectional winds. How pathetically par for the course! Maybe we’ll get some supercells, but we’re unlikely to see the low-level helicity needed to make them tornado producers. Probably better knock on wood when I say that, because the lake breeze zone can do some funny things with locally backed winds. Overall, though, I think the order of the day will be some nice, burly, ouflowish thunderstorms.

What do I know, though? I’m still pretty green as a forecaster, and I recall a couple years ago when the models showed a unidirectional setup with nothing in the way of helicities, and an F3 tornado ripped through Potterville.

One of the nice things about living in Michigan this time of year–among the many wonderful advantages of this beautiful state–is that we’re prone to get a couple supercellular events when the traditional Tornado Alley of the Great Plains simmers under a titanium cap. Those occasions aren’t anything you can count on, but it’s nice when they happen–for me and my fellow storm chasers, anyway. I suppose other folks here might see things a bit differently.