It’s July 4, Independence Day. Happy Birthday, America! For all the problems that face you, you’re still the best in so many, many ways. One of those ways, which may seem trite to anyone but a storm chaser, is your spring weather, which draws chasers like a powerful lodestone not only from the all over the country, but also from the four corners of the world.

no images were found

This has been an incredible spring stormwise, but its zenith appears to have finally passed for everywhere but the northern plains. And right now, even those don’t look particularly promising. That’s okay. I think that even the most hardcore chasers have gotten their fill this year and are pleased to set aside their laptops and break out their barbecue grills.Now is the time for Great Lakes chasers to set their sights on the kind of weather our region specializes in, which is to say, pop-up thunderstorms and

no images were found

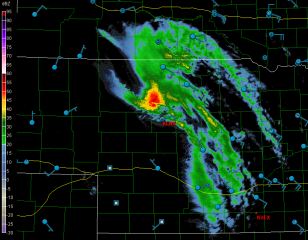

squall lines. The former are pretty and entertaining. The latter can be particularly dramatic when viewed from the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, sweeping in across the water like immense, dark frowns on the edge of a cold front. If you enjoy lightning photography, the lakeshore is a splendid place to get dramatic and unobstructed shots. Not that I can speak with great authority, since so far my own lightning pictures haven’t been all that spectacular. But that’s the fault of the photographer, not the storms.The images on this page are from previous years. So far this year I’ve been occupied mainly with supercells and tornadoes, but I’m ready to make the shift to more garden variety storms, which may not pack the same adrenaline punch but lack for nothing in beauty and drama.

July 4th is a date that cold fronts seem to write into their planners. I’ve seen a good number of fireworks displays in West Michigan get trounced by a glowering arcus cloud moving in over the festivities. But tonight looks promising for Independence Day events. Storms are on the way, but they should hold off till well after the party’s over. That means we’ll get two shows–the traditional pyrotechnics with all the boom, pop, and glittering, multicolored flowers filling the sky; and later, an electrical extravaganza, courtesy of a weak cold front. A Fourth of July double-header: what could be finer than that?