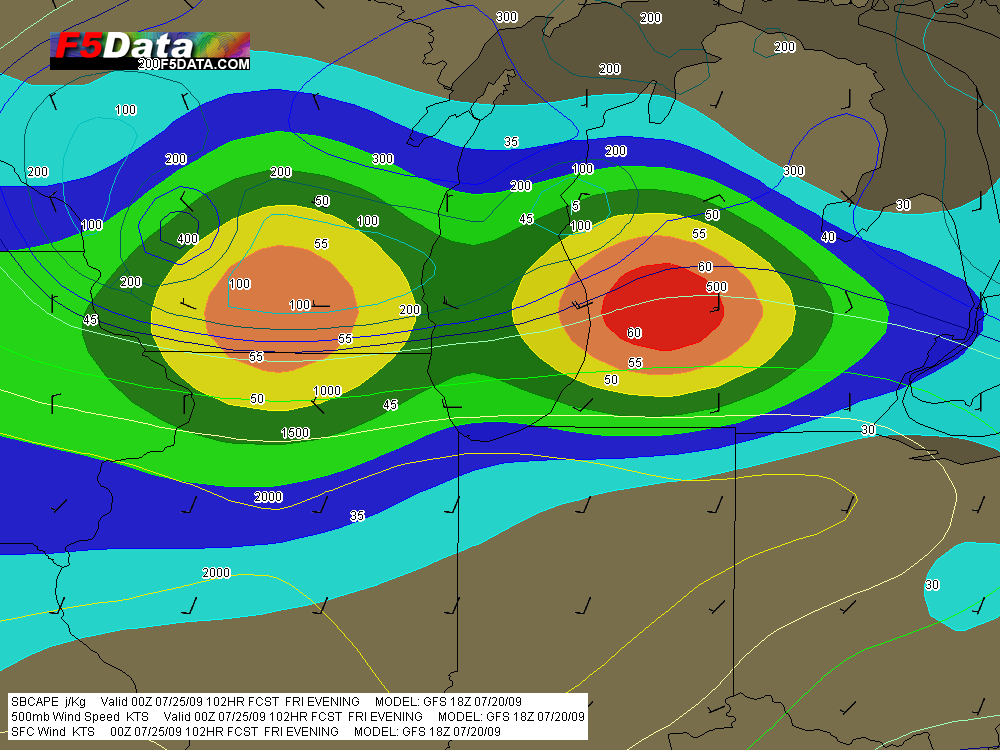

Out of idle curiosity, I ran the latest GFS and came up with the image below. The colored shading is 500 mb winds, and the contours are CAPE. Not shown: H7 temps of 4 C throughout Michigan, 50-60 kt bulk shear, and dewpoints in the mid-60s.

GFS for 00Z Friday evening, July 24.

CAPE stinks, but I’ve got to love that jet streak parked right over Grand Rapids. Without decent convective energy, this setup is hard to get too hopped up about, but it’s certainly worth keeping an eye on. Probably a pipe dream in July, but in this part of the country you just never know.