Saint Louis, Missouri, has been hit a number of times by tornadoes over the years, most notably on May 27, 1896, when a violent tornado claimed 255 lives. Last Friday my friends Bill Oosterbaan, Kurt Hulst, Mike Kovalchik, and I witnessed the first EF4 tornado to strike the metro area in 44 years.

I use the word “witnessed” loosely as we really didn’t see much of anything. Bill observed wrapping rain curtains just to our west, Kurt and Mike saw a couple power flashes, and I captured a feature on video that may have been the funnel cloud, but mostly what we saw was a whole lot of blowing rain and brilliant, nonstop lightning. Judging from the lack of any other videos that show a clearly defined tornado, our experience was typical. If anyone was in a good position to see the condensation funnel, it was us, and perhaps we would have seen it had the storm struck an hour earlier. But I suspect the thing was too rain-wrapped for good viewing even in broad daylight.

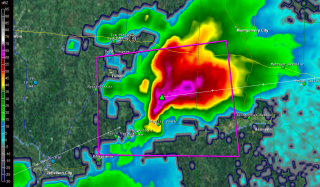

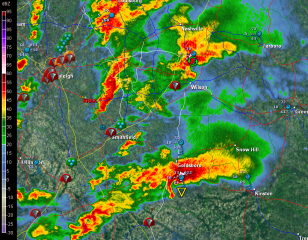

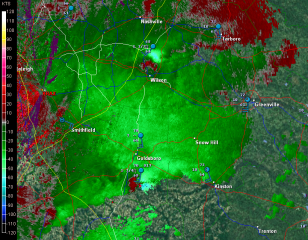

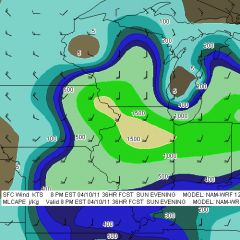

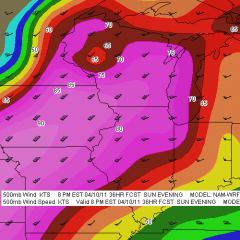

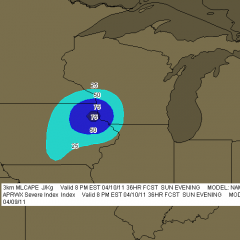

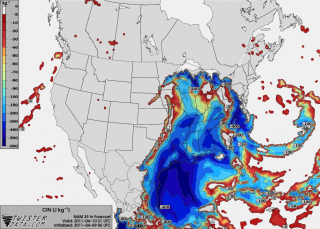

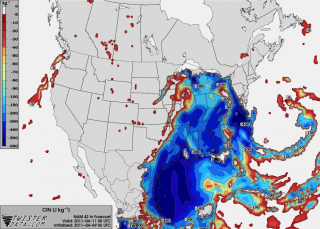

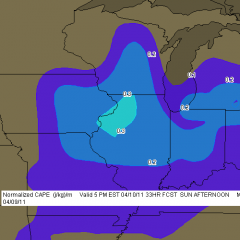

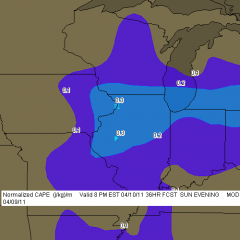

The storm initiated southeast of Kansas City near the triple point of an advancing low. Poised at the northernmost end a broken line that backbuilt southwest into Oklahoma, the incipient cell split and the right split grazed eastward along a warm front draped over the I-70 corridor.

We first intercepted the storm south of Columbia outside the town of Ashland. At that point it was getting its act together and was already tornado warned. The sirens sounded right next to us as we stood and filmed, but the storm had a ways to go before it finally went tornadic. Where we stood southeast of the updraft base, the air was dead calm–not even a breath of inflow, nothing but the year’s first mosquitoes to remind us that spring was well underway south of our home state of Michigan.

Keeping up with this storm would likely have been much easier had we not chosen to head back to I-70, where eastbound slowdowns hung us up and golfball hail on the north end of the supercell clobbered us. The storm organized beautifully for a while on the radar, but there wasn’t a thing we could do about it with traffic crawling along. Thanks to Bill’s great driving, we eventually did get clear, but by then the storm appeared to have turned to junk.

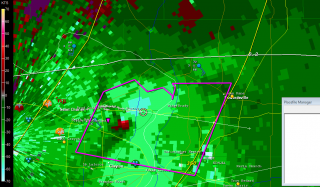

Just goes to show how deceptive appearances can be. Shortly after we had written the storm off, the radio announced the first reports of tornado damage in New Melle, and from then on, the reports continued. As fellow Michigan-based storm chaser L. B. LaForce put it, “I got a good look at the base just south of Innsbrook and it looked like crap. It tightened up shortly thereafter.”

Indeed it did, as strong and continuing radar couplets bore out. Dropping south on US 40 to get a better view of the storm, we parked by a cemetery and finally got a good look at the action area to our southwest. Against the dirty orange backlight of the fading sunset, a conveyor of low clouds flowed from the north into an area of murky blackness bristling with lightning. Unquestionably this beast meant business and intended to transact it along the worst possible path: right through the heart of northern Saint Louis.

Along its 22-mile path, the tornado inflicted its most widely reported damage at the Lambert–Saint Louis International Airport. It’s a miracle that no one was killed or seriously injured at this location. That may very well include us. We had exited I-70 in order to get a look at the storm, or at least try to, and by the time we were back on the highway the radar showed that we had compromised our safety and needed to git, fast. It was at this point that Bill thought he saw the rain curtains swirling, and Kurt and Mike observed what looked like power flashes. Hard to say, given the intensity of the lightning. What’s certain is that we missed the tornado by the skin of our teeth, because the radio announced only minutes later that Lambert Field had been hit. The bear had been breathing down our necks. Funny thing is, I’ve driven through much worse conditions at night. But conditions can change in a heartbeat, and in this case they wouldn’t have changed for the better.

The seriousness of the damage inflicted by this tornado didn’t sink in until a while later when reports, photos, and YouTube videos began to filter in. EF4 damage occurred about a mile-and-a-half west of the airport. At Lambert, the damage was rated EF2 and resulted in closure of the airport. A photo of a passenger bus hoisted up onto the roof of an airport building demonstrated the power of the winds.

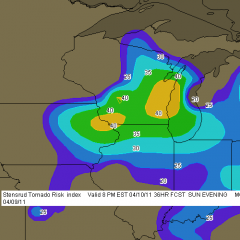

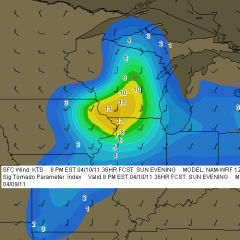

The Saint Louis NWS report on this event lists two tornadoes, the first a brief EF1 that did damage in New Melle, followed by the long-track, EF4 monster that chewed through Saint Louis proper, beginning along Creve Coeur Mill Road near Griers Lane and dissipating across the Mississippi River south of I-270 and west of Pontoon Beach, Illinois.

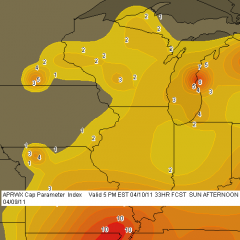

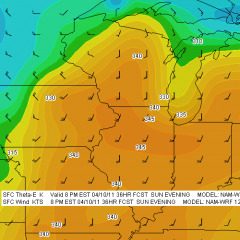

Why did the storm wait until it was just west of Saint Louis to begin spinning up tornadoes? The best explanation I’ve heard is one that was offered on Stormtrack. Evidently the warm front had moved north of I-70 on its western side, where the low initially lifted through Kansas City. But farther east, the front sagged southward through Saint Louis, backing the surface winds. The storm, moving eastward through the warm sector just south of the warm front toward an inevitable intersection, finally interacted with the front itself and began to ingest the enhanced helicities. Suddenly, boom! Tornadoes.

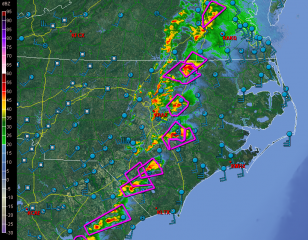

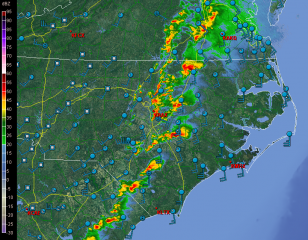

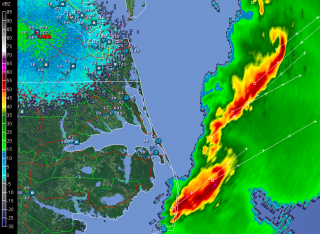

Farther east into Illinois, although it continued to be tornado warned, the storm gradually weakened and lined out, leaving Bill, Kurt, Mike, and me to enjoy a spectacular light show for much of the ride home. I finally clambered into bed around 5:00 a.m.

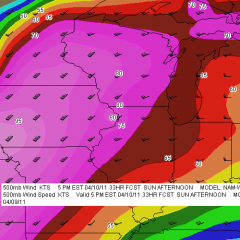

The stormy weather continues unabated down south. As I write, Bill is chasing down in Arkansas north of Little Rock. Judging by his position on Spotter Network, it looks like he may have bagged a tornado. Guess I’ll find out in a while. I wish I was there too, but this week is spoken for. I have a gig tomorrow afternoon, and then Mom goes in for knee surgery on Wednesday. So I won’t be chasing through the weekend. After that, we’ll see what the weather holds. This has become an active April, and now we’re coming up on May. I can’t wait to hit the road again!