This post is long overdue, but there has been no helping the time lapse between my first Great Plains chase of the year on April 13-14 and tonight, when I’m finally setting the highlights of those days briefly in print. The reason is that, upon my return home, I immediately succumbed to the worst case of acute bronchitis I’ve ever experienced. It was characterized by constant, deep, wrenching, non-productive coughing; a chronic sore throat; a fever that topped 102 degrees; an ear infection; laryngitis; plugged-up sinuses; and if I’ve missed anything else, let me just sum it all up by saying that I was in neither the condition nor the mood to do any film editing or writing, or much of anything except to attach my face to a vaporizer and to suck down Jell-O, chicken soup, sports drinks, ginger tea, and enough fluids overall to qualify me as a human aquarium.

Today, though, I am definitely on the mend, and it’s high time I got this report written. Tomorrow looks to be another big day in eastern Kansas, so I need to write before anything I have to say about an event from two weeks ago gets swallowed up in the latest round of wedges.

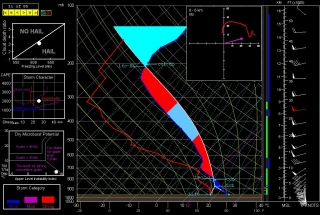

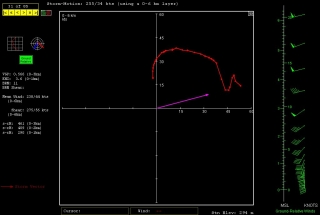

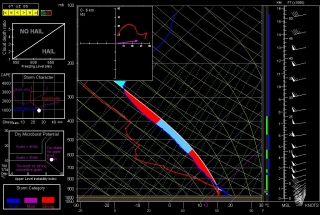

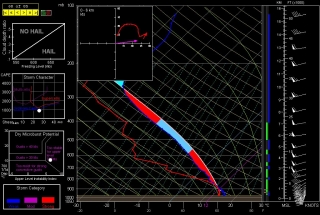

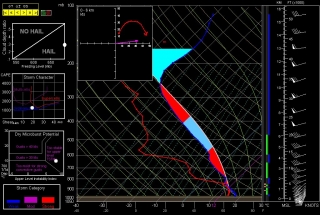

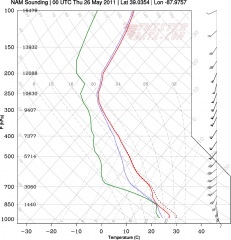

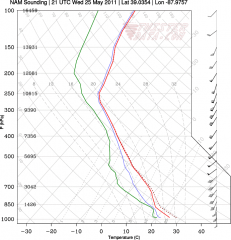

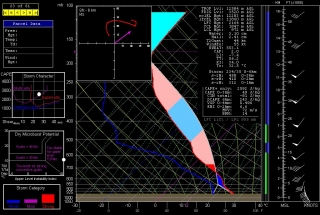

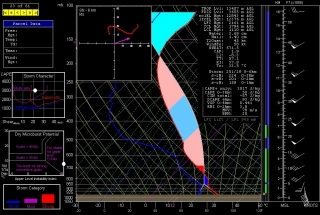

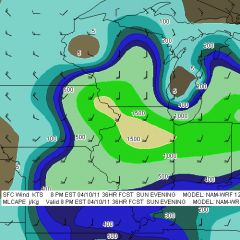

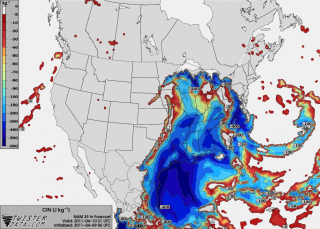

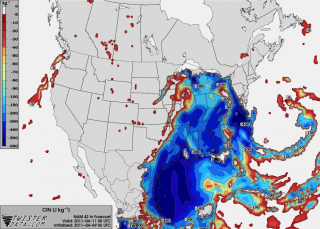

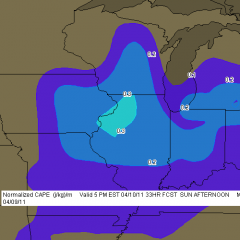

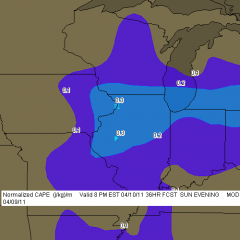

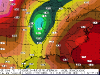

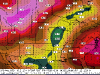

And it does look there could be some wedges. Look at this NAM skew-T and hodograph for Chanute, Kansas, at 00Z. (Thanks, Ben Holcomb, for tipping me off to Chanute!) With 1km and 3km SRH at 290 and 461 m2/s2 respectively and a nice, fat low-level CAPE, that’s the broth for some violent

tornadoes. I expect that part of the area that the SPC has categorized as a light risk for tomorrow will be upgraded.But I’m chasing rabbits. Getting back to the topic of this post: With conditions coming together for two or three days of severe weather in tornado alley from April 13-15, Bill Oosterbaan and I headed for Oklahoma in company with two new chaser friends. Rob Forry is a fellow chaser from the other side of Michigan who had yet to experience a Great Plains chase; and Steve Barclift is an editor friend of mine who, I discovered, shares my keen interest in severe weather and had been wanting to get a feel for storm chasing.

We arrived in Norman, Oklahoma, late in the morning on Friday the 13th. Dropping off our travel bags at the apartment of Ben Holcomb, who was graciously putting us up for the night later on, we promptly headed out for the chase.

We encountered our first storm of the day not far from Chickasha. Not being the superstitious type, I have no qualms about chasing storms on Friday the 13th; still, this storm gave us a shake when it led us back to Norman and spun a tornado within a mile of Ben’s apartment. We pulled out of chase mode long enough to make sure that Ben’s place was okay. Then we headed southwest a second time, this time plunging beyond Chickasha toward Boone and Meers, and thence into the heart of the Wichita Mountains. There, we positioned ourselves on the southeast flank of a tornadic supercell as it advanced slowly over the ragged landscape.

We may have witnessed a tornado at this point, but my video provides no conclusive evidence, just strong suggestions. Tornado or not, though, to stand in the inflow of that massive, beautifully crafted supercell and watch it spew lightning from its charcoal interior as it dragged across those prehistoric peaks was reward enough. No more need be said, nor shall be, since Friday was simply a scenic prelude to the action up in Kansas the following day.

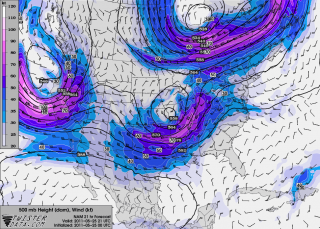

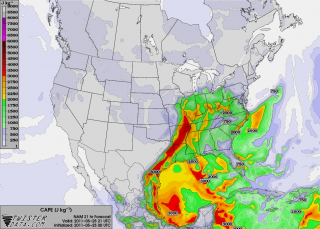

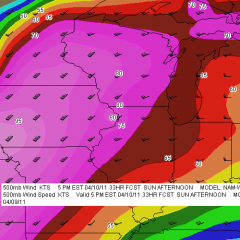

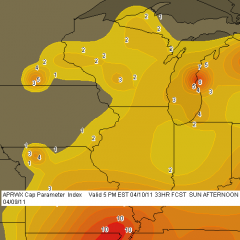

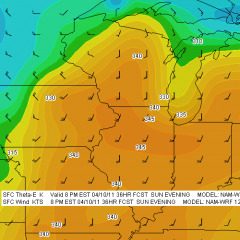

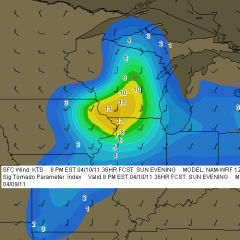

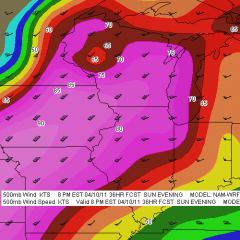

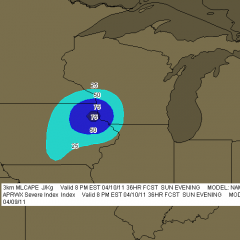

Saturday, April 14, dawned on a large high-risk region that ranged from most of central and eastern Nebraska south through central Kansas and down into much of central Oklahoma. With impressive upper- and mid-level jets overlaying the region, bulk shear was beyond adequate, as was instability. The ingredients were all there. Today, it seemed, would be one of those days when anyone who chased–and there were lots of chasers prowling the prairies on this day–would see a tornado.

In practice, though, it wasn’t quite that easy. Our plan was to drift up I-35 and then head west toward a likely looking storm. Not a very sophisticated approach, but it seemed likely to work, and in fact it did. We weren’t far across the Kansas border when we decided to turn west, and in a while we encountered our first supercell of the day, and with it, our first tornado. The cone spun at a good distance, probably five miles or more away. Looking at my video clip, I’m satisfied that it was indeed a tornado–even at that distance, the outline is distinct and separate from the storm’s rain shaft.

We stuck with our storm as it sailed north-northeastward, but it seemed to be having a hard time establishing itself beyond its first tornadic salvo. Still we stayed with it, hoping it would organize into a rumbling monster. But it continued to attenuate into a skinny, sorry-looking mongrel, so we finally dropped it for a more promising-looking storm to its south.

I remember saying at the time, “Dropping this storm [which I was in favor of doing] could be a really good decision. Then again, the storm could reorganize in half an hour and start putting down hoses.” Of course, the latter is what happened. Half an hour or forty-five minutes later, the storm we had put behind us had morphed into a supercell that, from the looks of it on radar, clearly wasn’t fooling around, and it went on to produce a string of tornadoes.

But by then we were committed to the storm to its south, a deceptively imposing-looking beast that washed out on us as we tangled with it and ultimately disappeared completely from the radar screen. Long before that happened, we wisely abandoned it for the next storm down the line, and as the saying goes, the third time was a charm. Just drawing closer to the storm environment, we could tell that this storm was of a different caliber. There was more lightning. The inflow was strong. The thing just felt tornadic. And it was.

From here on, I’ll let my video clip tell the story. It chronicles our chase from near Pretty Prairie, where we encountered our first tornado with this storm at close range with rain bands wrapping toward us, on north-northeastward toward Lost Springs and Delavan. The latter, night-time portion of the video is best viewed in dim light.

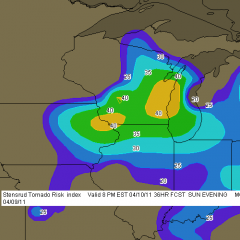

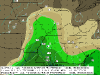

On a side note, the SPC did a great job of forecasting this widespread outbreak, as you can see from this verification of the outlooked areas with confirmed tornadoes. One thing that puzzles me is why they showed a 45 percent hatched area for Nebraska, when from what I recall, the NAM and RUC didn’t appear at all bullish for a northern play. At the time, I figured that those SPC guys must have known something that the models weren’t revealing, but in fact the majority of tornadoes occurred southward in Kansas. If anyone from the SPC happens to read this, I’d welcome your comments on the thinking behind the enhanced focus on Nebraska over regions southward.

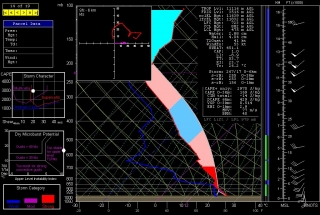

We overnighted east of Kansas City, and the following day found us chasing a warm-front scenario in south central Minnesota. The setup this day was utterly unlike the previous day. In fact, with the surface low nearly collocated with a closed 500 mb low to our west, we were dealing with what seemed like a quasi-cold-core setup. The storms, low-topped supercells, formed in convective “streets” that moved nearly straight northward, each street progressively kicking off new convection to its east where outflow presumably converged with strong southeasterly surface winds. Tornado reports occurred to the north, along or just past the warm front, where winds backed strongly.

The setup was an interesting one particularly in that tornadoes were reported on the cold side of the front, which cooled markedly within a matter of a few miles. This seemed counterintuitive: what kind of surface instability was available in such an environment? I recalled my chase with Kurt Hulst and Dave Diehl back in February, 2006, when we watched a storm on the far eastern side of a cold core drop a tornado several miles to our south. Where we stood, the air was so cold that I could see my breath; yet across the distant treeline, an unmistakable tornado was spinning and doing damage in a small town east of Kansas City.

As for this present date, while the four of us didn’t see a tornado on April 15, we did see the most wildly circulating wall cloud I’ve ever laid eyes on. The motion in the thing was unreal, something I attribute to the storm’s crossing the warm front and encountering a radical backing of winds.

Inevitably, we found ourselves in Minneapolis, at which point we left chase mode and headed for home. The first few coughs that would rapidly blossom into the debilitating bronchitis I mentioned at the start of this post were just getting hold of me. The following day would mark the beginning of a miserable two weeks. I’m just glad the virus held off till I got home.

Now I’m almost recovered–not in enough time for what looks to be a lively day in Kansas tomorrow, but certainly for the next round after.

For another perspective and some absolutely stunning videos of the Kansas outbreak of April 14, visit my friend Kurt Hulst’s blogsite, Midwest Chasers.