A few months have elapsed since my last post, which covered the Great Galesburg Earthquake.* I’ve been quite busy with book editing and copywriting and with a move in June from Caledonia to Hastings. So storm chasing this year has once again been mostly theoretical. If there’s anything good about that, it’s that missing out on yet another chase season hasn’t bothered me as much this year as it has in the past. There’s a lot to be said for loving what one does but not being owned by it. That’s not to say, though, that there weren’t times this spring when memories of past chases washed over me, and thoughts of towers punching up into the troposphere, of gorgeous storm structure, and of the smell and feel of Gulf-moistened inflow whisking across the prairie grasses toward an updraft base, made me wish like anything that I was out on the Plains once again.

Well, one takes life as it comes, and part of its lesson is to look for and appreciate the good one has rather than bemoan the good one is missing. Lack of chasing has been compensated, at least somewhat, by an increase in musical opportunities. And at this time in my life, I think it is important that I take those opportunities, which are rewarding aesthetically and which augment my finances and pave the way to more gigs, more musical involvements, and a broader future doing the other thing besides storm chasing that I love.

Don’t misconstrue this to mean that I’ve died to chasing. That’s not likely to happen; once chasing is in your blood, it becomes a part of you, and it has been in my blood for many years. No, it’s simply to recognize times and seasons, and to refuse to be shaped by the obsessiveness that is a very real aspect of storm chasing culture. I’m too old not to know better by now, and I’d be a fool not to live by the wisdom I’ve gained. One of what Paul the apostle called the “fruits of the Spirit” is self-control. Restraint. The ability to judiciously govern one’s impulses—not squelching them, but rather, choosing not to let them run roughshod over other very important things in life.

With that little preamble . . . severe storms are in the forecast for later today, and playing my saxophone has been very much in the foreground of my life lately, and this post will cover a little bit about both storms and jazz.

Weatherly Speaking

Yesterday evening I gave a presentation on storm chasing at the William P. Faust Public Library in Westland, Michigan. It was a great time with a small but engaged audience of roughly twenty people. My presentation runs around an hour-and-a-half, including time for questions at the end. However, I encourage my listeners to ask questions during the presentation as well, as I think an interactive format makes things more interesting and develops a connection with my audience.

This presentation was my second at this library and my fourth in all, and in my opinion, it was my best. With each one, I feel more familiar with my material and more at ease and spontaneous as a public speaker. Once I share the ten-minute clip of my March 2, 2012, chase of the Henryville, Indiana, tornado, I’ve got a captive crowd, and I can then move on to basic storm forecasting, supercell structure, and tornado safety, with a strong emphasis on safety. In the process, I make a point of advocating for NWS forecasters, explaining why weather professionals in Michigan have a particularly tough job protecting the public; and of debunking the largely mythical mantra of “We had no warning,” strongly insisting that the responsibility for safety rests in people’s own hands.

My sister, Diane, came with me and in fact did the driving, and it was a blessing to spend time with her. She’s a busy gal these days, and I’m a busy guy, and we just don’t get to spend much quality time together. So the chance to get away with her for an afternoon and evening was a gift. Plus, now she knows what my presentation is like, and how it can be adapted if the school where she teaches, Forest Hills Northern, wants to bring me in sometime.

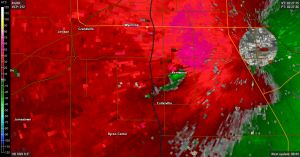

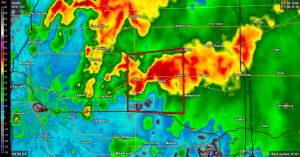

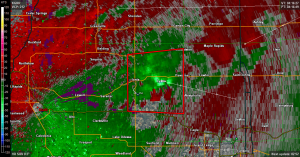

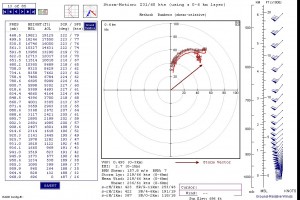

All in all, yesterday went beautifully. And now today the potential exists for severe storms this afternoon and evening, contingent upon sufficient CAPE and adequate shear. The SPC even indicates a 2 percent tornado risk, but that’s Michigan for you—just enough to tease, and maybe there’ll be a spinup or two on the east side of the state.

As I write, noon is at hand, a brisk southerly surface wind is playing through the tree branches in the backyard, and breaks in the clouds and a dry slot moving in from the west suggest a buildup in instability. Time will tell, but I anticipate some kind of local chase and am ready to roll.

Music

These past few weeks have been filled with more music than I’ve seen in I don’t know when. I played my first gig as a strolling saxophonist for the VIP pre-grand opening of Tanger Outlets here in Grand Rapids. That was fun, and a nice piece of change, and it was all the more enjoyable thanks to a chance to sit in with Mark Kahny and Bobby Thompson, who were performing onstage at a different location in the outdoor mall.

Then two days later came the first of two Saturday evening gigs with My Thin Place, a collective led by bassist Dave DeVos and featuring Mike Dodge on guitar, Dave Martin on vibraphone, and Ric Troll and Fritz von Valtier alternating in the drum chair. The venue for both dates was the outdoor patio at Sandy Point Beach House, a restaurant right by the lakeshore between Grand Haven and Holland. It’s as idyllic a setting as you can imagine for a jazz gig, and the music this combo performs—a mix of ECM-style tunes, original compositions, and American songbook charts—was the perfect complement to outdoor dining.

After the gig at Tanger Outlets, Mark Kahny contacted me about joining him and Bobby for a gig at the What Not Inn in Fennville. I was delighted! These guys are superb, not only musically but also as entertainers who know how to engage their audience, and we gelled beautifully in that small but popular setting. The result was musical magic. Guys, if you read this, please bring me aboard again real soon. I love making music with you!

Now let’s talk about Big Band Nouveau. Whew! Three major gigs in a week in Grand Rapids, starting with the West Michigan Jazz Society’s Monday evening Jazz in the Park concert at Ah-Nab-a-Wen Park on the riverside; then Thursday night at Bobarino’s at The B.O.B., with a wonderfully supportive audience; and concluding with a Sunday afternoon encore performance at the GRand Jazz Fest on the Rosa Parks Circle stage. What can I say about this band? The charts are contemporary, challenging, and tasty, giving soloists plenty of room to stretch; and the musicians are outstanding—a bevy of strong soloists with individual voices. No wonder this band gets standing ovations! Its star is rapidly—and deservedly—rising, and I am privileged to be a part of it.

To top it all off, later Sunday afternoon I attended Mark Kahny’s annual music bash at his house in northeast Grand Rapids. This was my first time there, and I had an absolute blast. Mark clearly designed his outdoor deck with the idea that it would serve as a stage for performances, and I joined him and Bobby to provide music for a legion of Mark’s fans. He’s been doing music for a long time, and people love him because he loves them. The party is for them, and they come, and it’s a beautiful thing. My old friend Freddy DeGennaro was also there with his guitar, as were several vocalists, and the music just flowed. I left Sunday evening feeling both tired and elated, appropriately depleted yet also energized. It was a great time, and an inspiring ending to a hot, humid, sweaty, and totally fantastic August day.

Speaking of which, another such high-humidity August afternoon is unfolding, and it’s time for me to unfold with it. Dewpoints are ranging from 68 to 72 degrees and the first line of storms has organized east of I-69/US 27. I bid you sayonara, dear reader. I’ve got a shower to take, a book to edit, and, in a few hours, storms to enjoy.

________

* Update: reports of prehistoric reptiles released from magma-spewing fissures remain unverified and should be viewed as suspect.