The Storm Prediction Center’s Day Three Convective Outlook has stamped lower Michigan with a “See Text” attended by the following discussion:

A POCKET OF COLD

TEMPERATURES AT MID LEVELS…MINUS 18-20C AT 500 MB…WILL SPREAD

ACROSS LOWER MI JUST NORTH OF A FOCUSED SPEED MAX. THIS FEATURE

WILL LIKELY INDUCE DIURNALLY ENHANCED CONVECTION AS 50F+ SFC DEW

POINTS SURGE NWD WITHIN THE WARM CONVEYOR. LATEST FORECAST

SOUNDINGS SUGGEST SFC-BASED CONVECTION IS POSSIBLE WITHIN A STRONGLY

SHEARED ENVIRONMENT THAT WOULD OTHERWISE FAVOR SUPERCELL

DEVELOPMENT. GIVEN THE SOMEWHAT LIMITED BOUNDARY LAYER MOISTURE

ACROSS THIS REGION WILL NOT INTRODUCE HIGHER SEVERE PROBS ATTM.

HOWEVER ANY UNDERESTIMATION IN LOW LEVEL MOISTURE WILL LEAD TO A

MORE UNSTABLE AIR MASS THAT WOULD SUGGEST AN INCREASED RISK OF

SEVERE FROM EXTREME NRN IND/NWRN OH INTO LOWER MI.

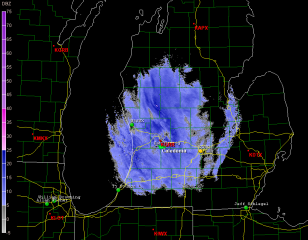

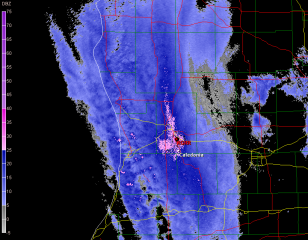

Hmmm…okay, that’s worth looking into, and I have done so. The NAM surface map is more optimistic about moisture than the GFS and SREF, wanting to bring in mid-to-upper-50s surface dewpoints, and therein lies the possibility for severe, from what I can see.

Today’s 12z 250 mb 4km NAM also shows a 70 knot jet streak moving into the area on top of 35-40 knot 850 mb winds, and GFS is in better agreement with the shear than it is the moisture.

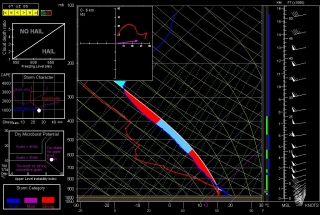

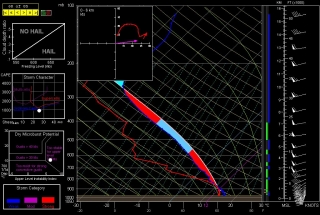

Earlier on, I also sampled a few 6z Bufkit NAM soundings using RAOB, and these show impressively curved hodographs–a different story from TwisterData’s point-and-click hodos–as well as dewpoints tapping on 60 degrees. That seems pretty exuberant, particularly in the light of other forecast models, but it does give me at least this take-away wisdom: Monday bears keeping an eye on. If, as the SPC states, decent moisture manages to infiltrate lower Michigan, then we could be in for some severe storms.

Just for kicks, below are the aforementioned RAOB forecast soundings for Monday evening taken from this morning’s 6z NAM run, along with the 4km NAM 250 mb map. The soundings are for Kalamazoo, Jackson, and Fort Wayne. Take them with a grain of salt, but let’s see how things shape up (or not) between now and then.

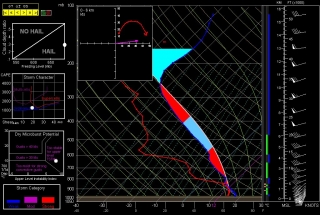

KALAMAZOO, MI

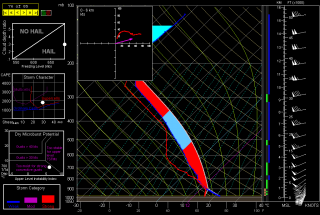

JACKSON, MI

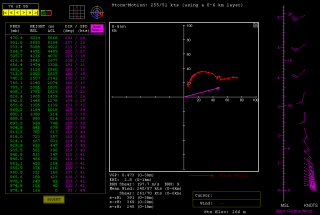

FORT WAYNE, IN

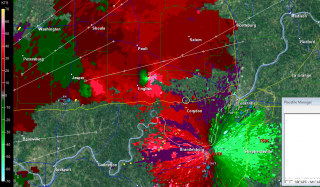

250 MB WINDS (FCST 21Z)

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel.

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel. color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.

color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.