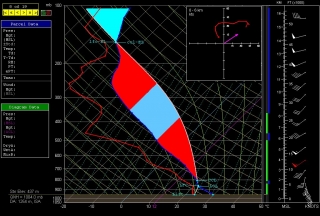

These next few days look interesting severe-weatherwise from the northern Plains into the Great Lakes. Today holds the potential for a significant blow near the Missouri River in South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa. Here is a RAP forecast sounding for Sioux Falls, SD, for 00z tonight.

I’ve been eyeballing that area via the NAM for a number of runs. Capping has been an issue for a while now, but NAM has consistently wanted to break the cap in the area I’ve mentioned. If I could have found a partner to split costs, I’d have left last night, but the thought of going it alone and blowing a wad of cash on a cap bust–a distinct possibility, with 700 mb temps hovering AOA 12 degrees C–spooked me.

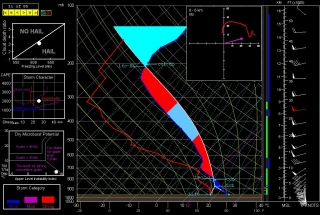

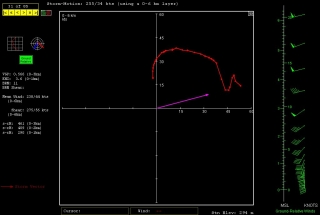

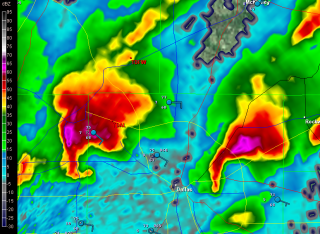

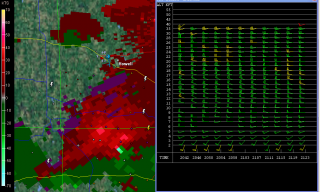

Now I think I should have taken the risk. Today could be another Bowdle day, and I wish I was in Sioux Falls right now. Some of the indices there for this afternoon look pretty compelling, at least if the RAP is on the money. The cap could break between 22-23z, and if that happens, then walloping instability (mean-layer nearly 3,900 J/kg CAPE and -10 LI) and mid-70-degree F surface dewpoints will surge upward into explosive development, and ample helicity will do the rest.

However, the SPC is not nearly so bullish as the above sounding, citing the complexity of the forecast due to capping and the lack of dynamic forcing. That’s been a repeated theme. Today looks like one of those all-or-nothing scenarios where chasers will either broil in a wet sauna under merciless blue skies or have one heck of an evening.

Boom or bust for those who are out there. As for me, this evening I will either be watching the radar and beating my head against the wall or else congratulating myself on my good fortune for not going.

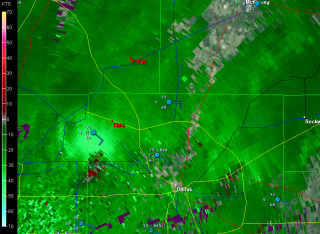

But I’ll also be packing my gear in preparation for tomorrow, and later tonight I’ll be hitting the road with Bill and Tom. I’m uncertain what Sunday holds, but last I looked, the dryline by the Kansas-Nebraska border looked like a possibility on both the NAM and GFS. The weak link seems to be the dewpoint depression; it’s wider than one could hope for, suggesting, as the SPC mentions in its Day 2 Outlook, higher LCLs. I haven’t gone more in depth. We’ll look at the model runs again tonight and pick a preliminary target for tomorrow.