There’s nothing fancy about these pics. They are what they are. But after a tremendously frustrating May–a rant I won’t even bother to get into right now–it is nice to have at least something to show.

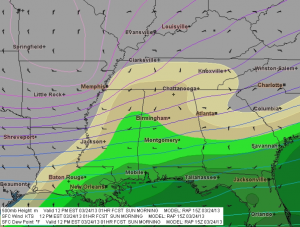

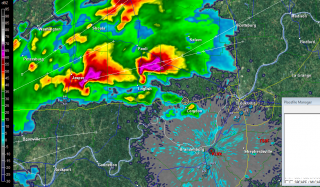

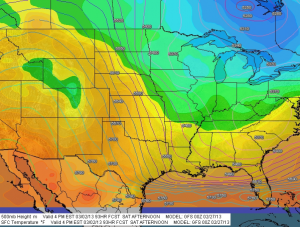

The setup was a warm front strung from Iowa eastward across northern Indiana, typical of the south-central Great Lakes region. While the NWS was talking of a derecho, forecast soundings a couple days in advance seemed to point to tornadic potential. And indeed, on the day-of, the SPC issued a high risk across the area, with a 10 percent hatched tornado risk in the area where Kurt Hulst and I chased and a 15 percent hatch farther to the west.

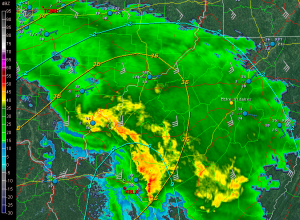

The photos show what we came up with in northwest Indiana south of Koontz Lake. The first blurry shot is of a small mesocyclone on a storm which, on the radar, gave only small hints that it could harbor one. Sometimes, given the right environment, what base reflectivity renders as amorphous blobs can provide surprises where you find a little sorta-kinda-almost hooky-looking little notch, and that was the case here.

The photos show what we came up with in northwest Indiana south of Koontz Lake. The first blurry shot is of a small mesocyclone on a storm which, on the radar, gave only small hints that it could harbor one. Sometimes, given the right environment, what base reflectivity renders as amorphous blobs can provide surprises where you find a little sorta-kinda-almost hooky-looking little notch, and that was the case here.

For a minute, it actually looked like it might give us a tornado, but the lack of surface winds was a good clue that wasn’t gonna happen. Structurally, though, this little storm offered an interesting opportunity to try and read clues in the clouds as to what it was doing or planned to do. I’m not sure I ever did figure that out, but it was fun to watch.

After watching it for several minutes, we dropped it to intercept the larger, more robust cell advancing behind it. This storm had displayed prolonged rotation on radar, and as we repositioned near a broad stretch of field that gave us a good view, we could see a stubby tail cloud feeding into a large, flange-shaped meso. The storm was clearly HP, with a linear look to it that suggests a shelf cloud, but there was no mistaking the broad rotary motion, and you can make out some inflow bands in the picture. At one point, a well-defined funnel formed just north of the juncture with the tail cloud (or whatever you want to call it) and the rain core, drifting behind the core and into obscurity.

After watching it for several minutes, we dropped it to intercept the larger, more robust cell advancing behind it. This storm had displayed prolonged rotation on radar, and as we repositioned near a broad stretch of field that gave us a good view, we could see a stubby tail cloud feeding into a large, flange-shaped meso. The storm was clearly HP, with a linear look to it that suggests a shelf cloud, but there was no mistaking the broad rotary motion, and you can make out some inflow bands in the picture. At one point, a well-defined funnel formed just north of the juncture with the tail cloud (or whatever you want to call it) and the rain core, drifting behind the core and into obscurity.

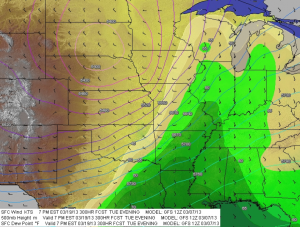

We played tag with this storm for a while, but it was toward sunset and getting darker and darker, and eventually we decided to call it quits and head back. The storms where we were just lacked the low-level helicity to go tornadic. There was ample surface-based CAPE–somewhere in the order of 3,000 J/kg, methinks– but whatever inflow was feeding them appeared to be streaming in above ground level.

So we headed back into Michigan, and as we drove north on US-31 near Saint Joseph, things got interesting fast. Green and orange power flashes suggested that a high wind was moving through nearby. A glance at the radar and, sure enough, there it was: a bow echo. It didn’t look terribly dramatic on radar, but looks can be deceiving.

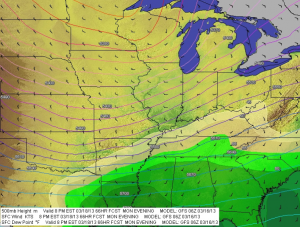

Heading east on I-94, we attempted to catch up with the belly of the bow as it rocketed toward Paw Paw and Kalamazoo. The next fifty or sixty miles was a millrace of frequently shifting high winds and torrential rain punctuated by power flashes. At one point, we narrowly missed running into a highway sign that blew across the road in front of us. At another, we passed an inferno where a falling tree had evidently gotten entangled in a power line.

North of us on the radar, we could see a supercell moving over the town of Wayland. But it was a little ways beyond reach, particularly given the kind of backwoods territory that lay to its east.

The high winds and driving rain ended, ironically, as we entered Kent County. My little hometown of Caledonia got just a relative dusting of rain and maybe a zephyr of outflow. It was hard to believe how much drama was playing out just a few miles to the south.

Big thanks to Kurt for taking me out with him when I didn’t have the gas or the money to chase on my own. I needed to get out and chase, and the sneering irony of having a robust setup dropped in my backyard and not being able to do anything about it was really eating me yesterday. I got to go out after all, and it felt wonderful.