Every year, the same question inevitably comes up: What is the upcoming tornado season going to be like?

The only truly definitive answer is no definitive answer. No one knows for sure till spring arrives, and the best any of us can go by are guesses, some better informed than others. I’m prepared to offer a few thoughts on the matter, but that’s all they are: thoughts, sheer speculation, items for consideration, not convictions or predictions; and they are those of a layman, not a professional meteorologist or a climatology expert.

With that caveat clearly stated, I have some hopes that this year will offer a few more “big” chase opportunities than 2012. True, the horrible drought that put the kibosh on setups last year after April 14 hasn’t gone away, nor does it show any sign of letup. And without any evaporative boost from moist earth or vegetation, dewpoints are apt to mix out in the Great Plains. That’s no news to anyone.

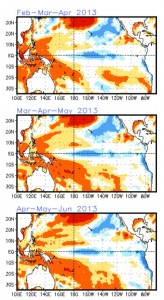

However, I have noticed that sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are above normal, and the CPC’s (Climate Prediction Center) ENSO maps forecast them to remain so. Below are the most recent maps, current as of January 28, covering the period from February through June, 2013. Click on the image to enlarge it. At the top right, you’ll see the Gulf of Mexico shaded in orange, indicating an average temperature deviation of 0.5 to 1.0 degree Celsius above normal closer to shore, and normal farther out.

However, I have noticed that sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are above normal, and the CPC’s (Climate Prediction Center) ENSO maps forecast them to remain so. Below are the most recent maps, current as of January 28, covering the period from February through June, 2013. Click on the image to enlarge it. At the top right, you’ll see the Gulf of Mexico shaded in orange, indicating an average temperature deviation of 0.5 to 1.0 degree Celsius above normal closer to shore, and normal farther out.

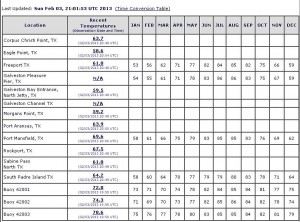

These are coarse approximations, of course. But you can drill down a little further by checking out current buoy observations against average station temperatures, courtesy of the NODC (National Oceanographic Data Center). Below is their table showing current station obs for February 3 to the far left; and, extending to the right of the obs from some of the stations, average normal monthly temperatures.* A quick glance will tell you that SSTs were well above average for this date, and in light of the ENSO maps, it seems reasonable to think that they will remain so. In fact, today’s and yesterday’s readings seem to be about a month ahead of the game, though granted, those are just two days, and there are bound to be plenty of fluctuations through the rest of the month.

What I feel safe in saying is that the overall higher SSTs in the Gulf of Mexico suggest a better moisture fetch than last year’s generally anemic return flow. Maybe the Midwest will benefit most from it, and I for one won’t weep if there are some decent setups closer to home. I can’t think of a better place to chase storms than the flatlands of Illinois.

However, it seems to me that Tornado Alley also stands a better chance of action as well, provided the polar jet cooperates this year by showing up farther south, where richer incursions of moisture can get at the energy. Neutral conditions that favor neither El Nino nor La Nina this spring strike me as more promising than last year’s La Nina.

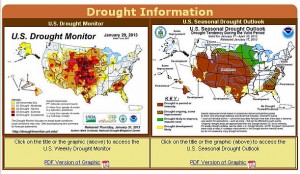

I weigh the above information against recent (i.e. January 29) CPC drought maps, which don’t paint the rosiest of pictures for most of the Great Plains but look good farther east and in the northern plains. Below is the most current drought monitor maps, released January 29; and the drought outlook, valid from January 17 through April 30.

Again, I’m neither a climatologist nor a meteorologist, just someone who likes to piece information together and see whether it bears out. Maybe it won’t. My original hunch was that, because of the drought, our storm season would be a repeat of last year’s, starting early and dying young. And maybe that’s the way it will be. But if I correctly understand the implications of warmer-than-normal GOM temperatures, it seems to me that this year could be at least modestly more active than last year’s abysmal storm season and might even hold a few surprises. It certainly can’t get any worse.

_______________

* Station observations shown are for the western Gulf. Obs for the eastern Gulf are also available at the NODC site.