I hadn’t planned to post today, but with the severe weather that the NWS has been forecasting for several days now already underway in east Texas and conditions ripening across southern Dixie Alley from lower Louisiana into Alabama, I thought I’d pin a few of today’s 12Z NAM forecast soundings to the wall to let you see what the squawk is about. I’m focusing on Louisiana because it seems to me that, from a storm chasing perspective, that’s where the best chances are for daylight viewing–not that I think there will be a whole lot of people chasing down in the woods and swamps on Christmas, but I need some kind of focus for this large and rapidly evolving event. Remember, the sun sets early this time of year.

To summarize the situation, a vigorous trough is digging through the South, overlaying the moist sector ahead of an advancing cold front with diffluence across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Shear and helicity are more than adequate for supercells and strong tornadoes, with forecast winds in excess of 100 knots at 300 millibars, 80 at 500, and 45-50 at 850, ramping up to 60 at night per the Baton Rouge NAM.

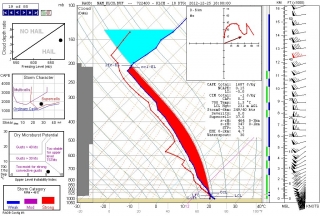

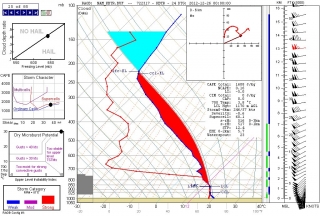

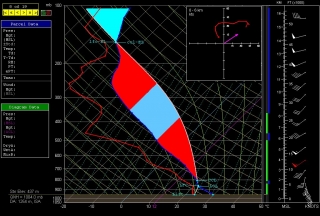

I’ll start with three soundings in southwest Louisiana at Lake Charles. It’s obviously a potent-looking skew-T and hodograph, with over 1,600 J/kg SBCAPE and more-than-ample helicity. No need for me to go into detail as I’ve displayed parameters that should be self-explanatory; just click on the image and look at the table beneath the hodograph.

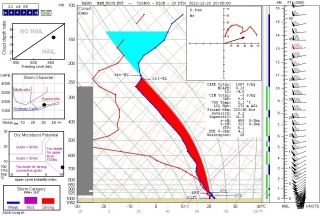

What I do find noteworthy is the very moist nature of this sounding, suggestive of overall cloudy conditions and HP storms. This changes quickly around 20Z (second image), with much drier air intruding into the mid-levels.

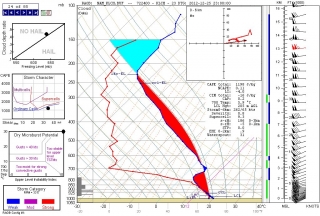

From there on, temperatures at around 700 mbs begin to warm up until by 23Z (third image) they’ve risen from 1.5 degrees C (18Z) to 5.9–a gain of nearly 4.5 degrees–and a slight cap has formed and becomes strong by the 00Z sounding (not shown). Note how the surface winds have veered, killing helicity as the cold front moves in. End of show for Lake Charles.

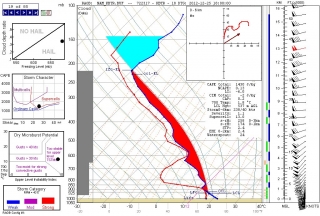

Farther east in the Louisiana panhandle, you get much the same story at Baton Rouge, except the more potent dynamics appear later and more dramatically, with 1 km helicity getting downright crazy. I’ve shown two soundings here. The first, at 18Z, has a dry bulge at the mid-levels but moistens above 650 mbs, and by 20Z (not shown) it has become even moister than its Lake Charles counterpart, to the point of 100 percent saturation between 600 and 800 mbs. Helicities are serviceable but less impressive than to the west.

There’s a big change in the second sounding, this one for 00Z. The dewpoint line sweeps way out, and look at that wind profile! With a 60 kt low-level jet, helicities are no longer also-rans to the Lake Charles sounding; at over 500 m2/s2, they’re hulkingly tornadic, and the sigtor is approaching 13.

Mississippi is obviously also under fire, and I hope the folks in Alabama have taken the 2011 season to heart and purchased weather radios that can sound the alert at night.

To those of you who chase today’s setup–and I know there are a few of you who are down there–I wish you safe chasing. But my greater concern is for

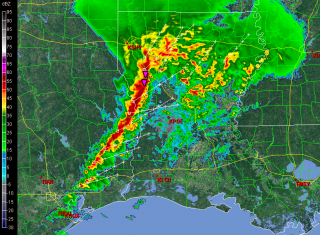

the residents of Dixie Alley who live in harm’s way and aren’t as weather-savvy, and some of who–despite the NWS’s best efforts–may not be aware of what is heading their way this Christmas Day.Having just glanced at the radar, I see that the squall line is now fully in play. I’ll leave you with a screen grab of the reflectivity taken at 1725Z.

Have a blessed and safe Christmas.

ADDENDUM: In watching the radar, it’s obvious that the 12Z NAM was slow by an hour or so. Can’t have perfection, I guess.