Thursday’s tornadic supercells in eastern Michigan took a lot of people by surprise–NWS and media meteorologists, the SPC, storm chasers, and certainly me. Nothing about those anemic mid- and upper-level winds suggested the potential for even weak tornadoes, let alone significant ones. But there’s no arguing with Nick Nolte’s fabulous footage of the Dexter tornado, and certainly not with the damage that storm did as it swept through the town. It has been rated an EF-3, the most damaging of the three tornadoes reported on March 15, 2012. Second in impact was a tornado that struck farther north in Lapeer, causing EF-2 damage; and finally, an EF-1 tornado in Ida.

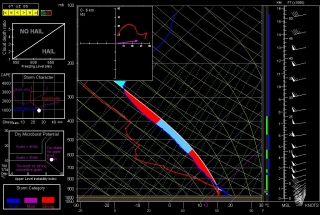

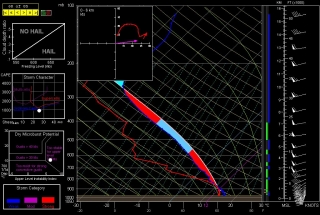

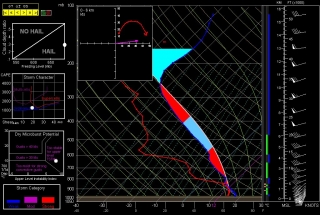

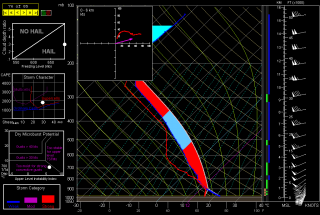

Like every other chaser in Michigan whom I know, I had no plans for chasing storms Thursday. True, temps were in the 70s and dewpoints in the 60s; MLCAPE was in the order of 3,000–3,500 J/kg; and the hodograph looked curvy.

But curvy alone isn’t supposed to cut it, not when the dynamics are as puny as they were: winds around 20 kts at 850 mbs; 20–25 kts at 700 mbs; and 25–30 kts from 500 mbs on up to around 26,000 feet, where they finally began to make incremental but hardly impressive gains. The storms that formed should have been popcorn cells that quickly choked on their own precipitation. But they didn’t. At least some of them became classic supercells that lumbered across eastern Michigan at around 15 miles an hour, spinning up strong tornadoes.

I was sitting in my living room editing a book manuscript shortly after 5:00 when I happened to glance out the window and saw some impressive, well-formed towers to my southeast. “Dang!” I thought. “Those look nice!” My second thought was to grab my camera and snap a few photos. After all, thunderstorms just aren’t something you normally see on March 15 in Michigan, let alone such muscular-looking ones. You can view one of the three shots I took–the last one, time-stamped 5:22 p.m.–at the top of the page. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

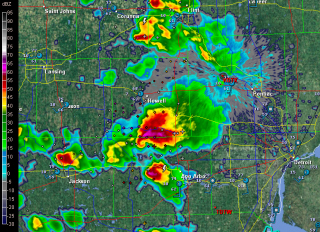

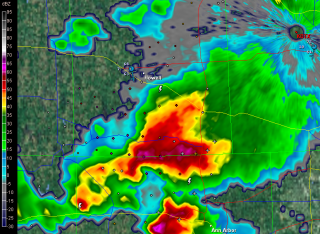

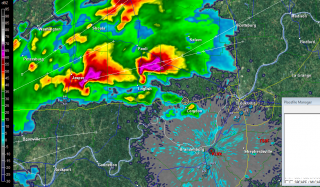

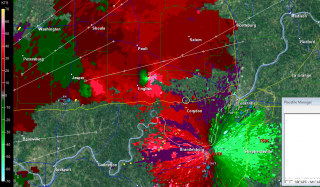

Curious, I took a look at GR3. I’d been glancing at it off and on as the afternoon progressed, watching a small squadron of cells pop up across southern and eastern Michigan. They resembled something I might normally see in July or August. But now, one of them looked different–so unexpectedly different that I had a hard time believing what I was seeing. South of Howell and northwest of Ann Arbor, the most vigorous-looking storm of the bunch had transformed into an unmistakable supercell–a regular flying eagle with a little pinhole BWER in the hook.

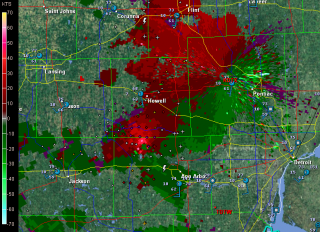

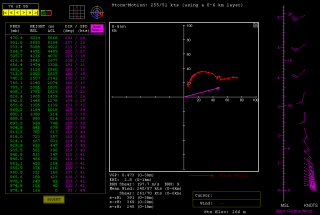

Where the heck did that come from, and why on earth was it there? Pinch me, I must be dreaming. I switched to SRV, and sure enough, there was a couplet, and not just a weak one, either. A pronounced couplet.

A scan or two later, the storm was continuing to develop. The pinhole had disappeared, and the supercell now had a classic hook. On radar, it looked as nice as anything you could hope to see out West in May–only this was Michigan in mid-March.

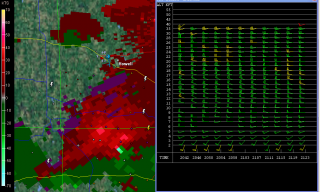

Surely the winds had to be better than I had been led to believe. One way to find out. I pulled up the VAD wind profiler at DTX. Ummm … well, okay. Nothing at all remarkable there. Maybe, given the curviness, enough bulk shear to organize the storm. Obviously that had to be the case; the evidence was staring me in the face, along with a couplet which hinted at the tornadic action that was presently occurring. The last screen capture, just below and to your right, shows both the couplet and the VAD. Enlarge the image, zoom in on it, and you can see for yourself just how meager the winds were and why one would expect storms forming in that environment to drown themselves in their own tears.

While I was glued to my radar in Caledonia, across the state storm chaser Nick Nolte was hot on the storm and videotaping the tornado that eventually hit Dexter. After getting out of work for the day, Nick had noticed the storm popping near where he lives. Grabbing his gear, he took off on what turned out to be one of the most serendipitous chases any chaser could hope for.

Nick got some fantastic footage of the Dexter tornado. Congrats, Nick–you really nailed it! Rather than steal Nick’s thunder by embedding his YouTube video here, I’m going to simply redirect you to his site and let you hunt it up there.

I’ve viewed some other footage beside Nick’s that demonstrates a particularly noteworthy aspect of the Dexter tornado, and that is its breakdown into helical vortices. I’ve seen only one other video that demonstrates this helical structure so clearly, and that is the famous KARE TV helicopter video of the July 18, 1986, Minneapolis tornado. The Dexter footage isn’t as dramatic, but it nevertheless depicts the helical effect with stunning and captivating clarity. Nick’s video captures it as well toward the end of his clip. It’s really amazing to see.

Unfortunately, the Dexter and Lapeer storms did considerable damage. If there’s a bright side to their human impact, it’s that no one was killed or seriously injured.

What turned yesterday’s anemic setup into a significant tornado-breeder? A weak upper-level impulse provided the needed lift to spark the storms, but it doesn’t explain why some of them developed into tornadic supercells, given the lackluster mid- and upper-level winds. I’m no expert, but I’m guessing that the unseasonably high CAPE is what did the trick. I suspect it took what was present in terms of shear and helicity and amplified it, in effect creating the Dexter, Lapeer, and Ida storms’ own mesoscale environments–ones conducive to tornadoes.

Of course, similar scenarios typically provide no more than single-cell and multicell severe storms. But then, yesterday was an anomaly in some significant ways. After all, this is Michigan, and it’s only mid-March. When CAPE of that magnitude shows up in the midst of unseasonably high dewpoints, it appears that all bets are off.

ADDENDUM: Lest you should miss reading the comments, check out this satellite loop from Thursday. You can see the storms exploding along an outflow boundary pushing west-northwest from Ohio, and other storms firing along a cold front dropping southeast. Two boundaries, and they actually appear to collide around Saginaw. The OFB accounts nicely for convergence and low-level helicity. Thanks to Rob Dewey for sending me the link.