When I started the Stormhorn blog two years ago, I envisioned two distinct readerships: storm chasers and musicians. Knowing nothing about blogging, I naively figured I could reach both audiences. I mean, what the heck, why not?

Amazingly, it seems to be working. The whole world may not be flocking to Stormhorn.com, but enough of you are finding your way here, and I’m encouraged to see the numbers steadily growing. Maybe that’s because musicians and storm chasers possess some important traits in common: a penchant for the unusual; a passion to excel; a thirst for personal involvement with something that is intense and deep; a fascination with how and why things work; a high degree of commitment and self-motivation; and a love of beauty.

For some of you, the focus is music. For others, it’s storm chasing. But both pursuits are fascinating and rewarding, and I’ve felt from the start that there’s a connection between them, and plenty of crossover appeal.

In fact, a good number of you bridge both worlds. In a recent thread in Stormtrack’s Bar & Grill (sorry, no link to the thread–B&G is a “members only” section), fellow chaser Wes Carter posed the question, “Who plays musical instruments?”

A fair number of you do, it turns out, including at least one who earns his living at music. That would be Huntsville, Alabama, blues man Dave Gallaher. Both as a solo act and with his trio, “Microwave Dave and the Nukes,” and also as a disk jockey for his twice-a-week radio broadcast, “Talkin’ the Blues,” Dave has made an impressive mark regionally, nationally, and internationally. A musician doesn’t accomplish something like that without paying some serious dues; it takes not only world-class skill, but also great crowd appeal and tremendous perseverance. You really want to check out Dave’s website.

Then there’s Brandon Goforth. While these days I’ve been hesitant to post YouTube links due to their unpredictable shelf life, I’d be remiss not to steer you toward this link featuring Brandon’s rock guitar artistry.The guy can play.

Dave and Brandon are just two stellar examples of people who are both musicians and storm chasers. There are plenty more. Maybe you’re one of them. Do you consider yourself primarily a musician who chases storms, or would you call yourself a storm chaser who plays music? Or are you, like me, so passionate about both pursuits that the question is irrelevant? Regardless, there’s an interplay between the two disciplines which suggests active minds with large appetites for life and learning.

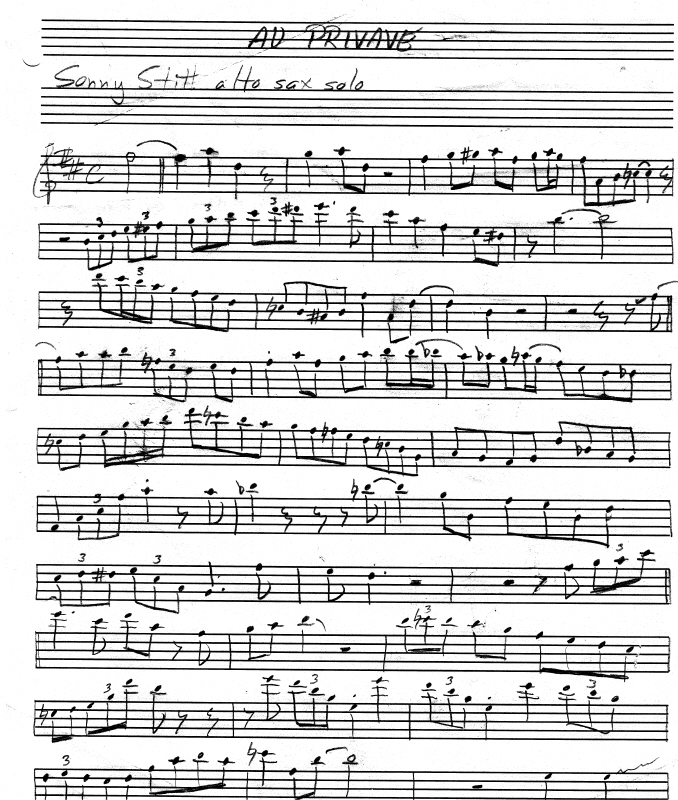

By the way, I’m never without my saxophone. I take it with me wherever I go, and that includes out to the plains when I’m chasing storms. Some chasers toss a football while waiting for initiation; I practice my sax. So to my fellow chasers who play an instrument (most likely guitar): if we cross paths and you’ve got your axe with you, we just may have the makings of an impromptu Great Plains jam session.

Keep your eyes open for me this coming spring. And if any of you happen to know of a good jazz venue in Tornado Alley, please let me know. Such places are hard to come by out west.