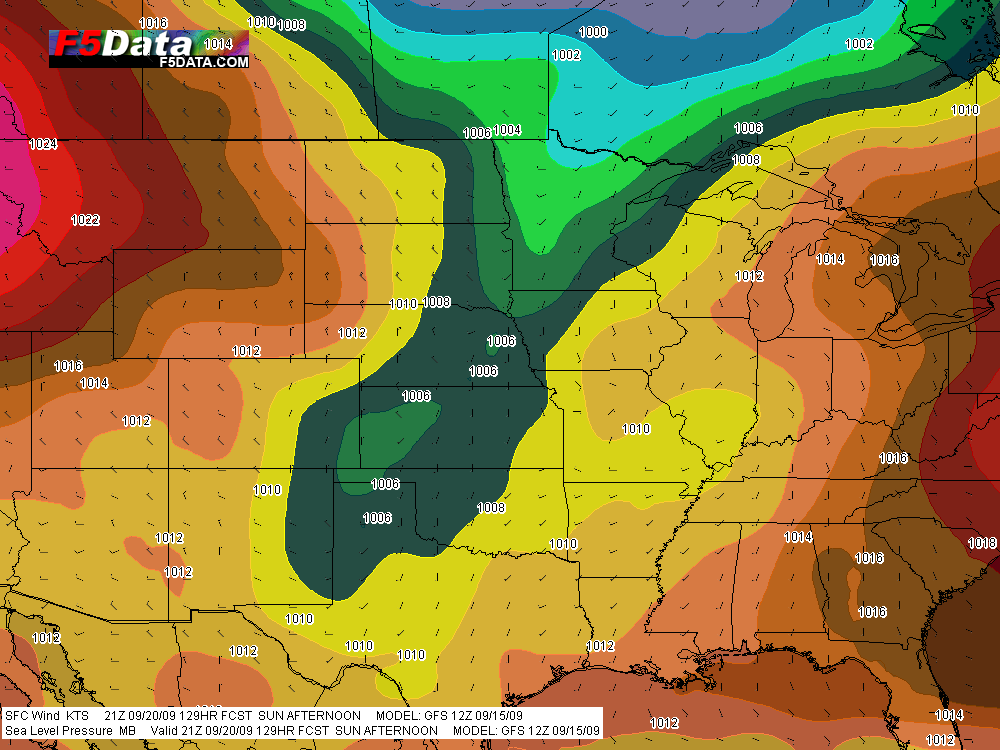

Storm chasers, check out the new RUC maps on my Storm Chasing page. They’re still under development, and they’re not comprehensive, but they do offer you something different. I haven’t seen F5 Data weather maps on other sites. If you’re a fan of tornado indices such as the EHI and STP, you’ll like the proprietary APRWX Tornado Index, which includes Great Lakes waterspouts.

For some strange reason, the surface dewpoint map keeps displaying surface temperatures instead. Not sure why, but obiously it needs fixin’. Everything else works as it should. I’ll welcome your comments/suggestions.