We were close to the tornado, roughly a quarter mile south of it, paralleling it as it tore an eastward course through the Illinois fields. Dirt and shredded corn swirled around its base like an aura. As Kurt Hulst and I pulled aside and stepped out of the car to take pictures, we could hear the roar. It wasn’t loud, just audible and big, very big, an intensely focused sound like an immense blowtorch or a rocket engine. Yet, close as Kurt and I were to the tornado, we were out of its path and beyond the range of any apparent debris, and I sensed no particular danger.

A brief staccato of blue flashes suddenly lit up the base of the funnel, accompanied by a loud bang, and chunks of debris flew skyward and centrifuged out. The tornado had hit a structure out in the field, most likely an outbuilding of some kind.

Fortunately, there was little real harm the twister could do out there in the broad Illinois prairie. Not yet, anyway. But a little way to the east lay Yates City, and two-and-a-half miles farther, the community of Elmwood…

The day had started off rather inauspiciously, with the previous evening’s aggressive SPC outlook degrading into a forecast for straight-line winds. The 12Z NAM, too, looked unpromising, and the RUC corroborated it, with mostly southwesterly surface winds veering with height to a unidirectional, westerly mid- and upper-level flow. A persistent batch of cloud cover from a mesoscale convective system threatened to minimize daytime heating and instability. In a word, the setup wasn’t one that suggested tornadoes.

But with a trough digging in from the west, rich moisture, great shear, and at least a semblance of clearing moving in from the southwest, Kurt and I decided to chance it anyway. Our friend and fellow Michigan chaser Ben Holcomb had alerted us the previous evening to the evolving weather situation, and after reading Friday night’s Day 2 Convective Outlook and scanning the NAM, which showed an impressive juxtaposition of the right ingredients, including high helicities stretching along I-80 from Iowa into Indiana, we knew that we had to go.

So off we headed for Illinois late Saturday morning. As Kurt pointed out, the forecast models don’t always have a good grasp on things. One thing we could tell from both the NAM and RUC, though, was that the best parameters now lay well south of I-80. Accordingly, we set our sights on Galesburg, and once there, we continued on, crossing the river at Burlington and heading west into Iowa.

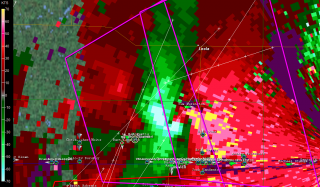

I took a dewpoint reading of over 72 degrees on my Kestrel at New London. The air was juicy. But the clearing we had driven through in western Illinois was giving way to a an extensive mid-level cloud deck. Rather than continuing to forge farther west toward the cold front, we decided to backpedal eastward in the hope that convection would fire near the edge of the cloud shield. This idea became a moot point as the cloud cover rapidly expanded across the river into Illinois. But better parameters still lay in our area. We were presently in an area of maximum sigtors and optimal 1 km helicity, and on the radar, a scattering of blue popcorn echoes suggested that localized convection was trying to get started. Anticipating that these features would all translate to the east, we drifted back in that direction.

We soon noticed a cloud base with a tower reaching up toward the higher cloud deck. It showed on the radar, as did another stronger one directly down the road from us. As we headed toward it, the second echo progressed from yellow to red. Not far to our northeast, we could see a rain curtain. Skirting it, we moved east of the developing storm cell, parked, and got our first good look at it.

The cell was organizing nicely and was already showing supercellular characteristics–nice separation of the saucer-like updraft base from the precipitation core; a strong, crisp, tilted updraft tower; the first signs of banding, and a hint of an inflow stinger. Positioned on the southeast edge of the convective cluster in southeast Iowa, it was in a favorable position to

ingest moist inflow unimpeded by other storms as it drifted at 30 knots toward Illinois.This was our storm. We tracked with it back across the river, watching it develop, watching the base lower and the first hint of a wall cloud blossom and put on muscle, watching it tighten as the RFD notch wrapped around it.

Just southeast of Maquon, Illinois, we saw it: a cloud of dust billowing up from the ground with brief, streaming tendrils of condensation forming and dissipating above it. Tornado! It was a brief appearance of maybe a minute’s duration, but the storm was just getting started, mustering energy for the next round.

We didn’t have long to wait. A minute or two later, as we proceeded down CR 8, a slender elephant’s trunk of a funnel probed its way earthward, intensified, and began gobbling its way through the corn, closing in to within a quarter-mile of us before turning straight east.

This turned out to be a beautiful, highly photogenic tornado, all the moreso for the amazing display of lightning that accompanied it. Kurt took some great video of it which will give you a much better appreciation for how

electrified the tornadic environment was. At one point, at the 8:50 mark, you can see a bolt shoot directly from the funnel to the ground. I didn’t have the good fortune to witness the famed Mulvane, Kansas, tornado, but I’ve got to believe that this storm was similar in terms of its incessant lightning.The funnel morphed through a variety of elegant formations, and the overall storm structure was beautiful. It was a stunning and mesmerizing sight, but with growing concern, Kurt and I realized that it was making its way toward Yates City and didn’t show any sign of weakening.

Fortunately, the funnel veered slightly to the northeast, passing just to the north of the town. At that point, it was an intense drillpress spinning furiously a mile distant. We closed the gap and tracked with it as it headed toward the larger town of Elmwood, just a couple miles down the road.

What was the funnel doing? It appeared to be shifting to the right. Oh my gosh! Elmwood was going to get hit! The tornado was beginning to rope out,

but not in enough time to spare the town. Taking a hard right, it plowed through the town center. Three-quarters of a mile ahead of us, power lines arced and transformers exploded, debris blasted into the air, and a large dust cloud billowed skyward.It is a weird and awful feeling to witness a community get hit by a tornado. I’ve seen it happen twice before in Springfield, Illinois, and in Iowa City, but those were night time events. It’s different in broad daylight, when you can see what’s happening. The rather blurry photo shown here was taken just before the tornado crossed Main Street in downtown Elmwood. It’s not a very dramatic shot. You can see a few pieces of debris floating in the air and no more than a cloud tag to mark the presence of the tornado. But a second or two after the photo was taken, things got very nasty in that town. If there’s anything at all good to be said about what happened there, it’s that no one got killed or, as far as I’m aware, even injured.

A couple hundred yards south of Elmwood, the tornado dissipated. Gone, poof, vanished just like that. There’s a certain ugly irony about a force of nature that can wreak havoc in a community and then vanish a few seconds later without a trace. If the tornado had dissipated just thirty seconds sooner, a lot of people might have experienced just a good scare rather than a local disaster.

Kurt and I continued tracking with the storm as it made its way toward Peoria. The next tornado soon formed–a larger, bowl-shaped cloud with multiple vortices. This broadened out into a large tornado cyclone with multiple areas of rotation that produced, among other things, a brief but spectacular horizontal vortex. Sorry, I have no photos to show of it. It had gotten too dark, we were moving, and any picture I took at that point would have been blurred beyond recognition.

In Peoria, we got a bit snagged by roads and traffic, but thanks to Kurt’s great driving, we soon found ourselves heading east on I-74. As we crossed the Illinois River, I could see what appeared to be a large cone funnel to our north making its way across what was probably Upper Peoria Lake, silhouetted by frequent strobes of lightning.

Catching CR 115 at Goodfield, we headed north to Eureka, then continued east along US 24. We were still tracking with the storm, which was slowly weakening as the next tornadic supercell to its north began to dominate. It was still no pansy-weight, though, and at Chatsworth, in a final show of strength, it spun down a brief but well-defined rope tornado.

As our storm merged with the northern storm around Kankakee, Kurt and I caught I-57 and headed home. After May 22 in South Dakota, I really didn’t expect that I’d get another decent storm chase in. But this El Nino year, which got off to such a rotten start for storm chasers, now is paying dividends with some highly photogenic tornadoes.

And the season isn’t over yet. There’s no telling what the rest of June may hold. I doubt I’ll be making any more forays this year into the Plains, but if the Great Lakes region continue to light up, I’ve got my camera and laptop ready.

To see more photos from this chase, click here. And while you’re at it, check out the rest of my images of storms, tornadoes, wildflowers, people, and whatnot in my photos section.