I initially became acquainted with Tim Vasquez’s books a good ten or so years ago at my very first severe weather conference at the College of DuPage. Tim was sitting at a table selling, among other things, his Weather Forecasting Handbook. I bought a copy and began chewing on it, and I have continued to do so ever since over the years. There’s a lot of essential information packed into the 204 pages of the old “Purple Book.” (Tim’s books are known colloquially by the color of their covers.)

That book took me deeper into a world of meteorological concepts that I was only beginning to become aware of, ones that storm chasers need to know. My brain not being the kind that readily absorbs such stuff by reading alone, it took me a long time and many read-throughs to grasp some of the arcane principles, language, and tools that are integral to making one’s own forecasts and selecting target areas. I still have a few things to learn–okay, plenty of things–but much of the material Tim covered is now familiar to me, and I apply it regularly.

Ragged and torn from long use, my old copy of Tim’s book sits beside me now as I write. Next to it is a brand-new copy of its heir-apparent, the Weather Analysis and Forecasting Handbook.

While anyone familiar with the old book will recognize much of the material, the new Purple Book is far more than just a makeover. At 260 pages, it provides considerably more information, all of it reflecting current research and technology. This is weather forecasting as it is today, not as it was a decade ago. Indeed, so much new material has been introduced; so much of the pre-existing text has been revised and expanded; the illustrations have been updated and extended to such a degree; and the content has been so thoroughly reorganized overall, with an eye on taking the reader beyond concepts to analysis and forecasting, that the Weather Analysis and Forecasting Handbook is for all intents and purposes a new book, not just an updated edition. And, I might add–and I say this rather grudgingly, having cut my teeth on the old handbook–this new volume is a more comprehensive and helpful resource than its venerable predecessor. There is just a lot more to this book, and it’s all presented in a well-thought-out fashion.

Main Content

One significant change in the Weather Analysis and Forecasting Handbook is the organization of its content. As does the previous book, this one begins by introducing foundational physical concepts such as mass, force, pressure, temperature, the Coriolis force, geostrophic wind, vorticity, and so forth.

The second chapter on observation also appears largely familiar, though it keeps abreast of current practices. However, the previous treatment of clouds is only lightly addressed because the subject is given an entire section of its own in the book’s appendices.

Beginning with chapter three, the changes become pronounced. Here is a very abbreviated overview of the book’s structure from this point:

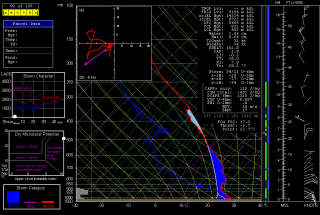

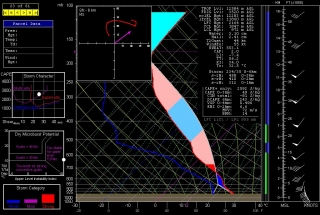

Chapter three: Thermodynamics–Deals with instability and familiarizes the reader with atmospheric soundings. Here is where you’ll learn how to read and interpret that essential forecasting tool, the skew-T/log-P diagram.

Chapter four: Upper Air Analysis–Taking a top-down approach to forecasting, this chapter introduces constant pressure charts, long waves and short waves, divergence and convergence, jets and jet streaks, and other atmospheric processes and influences from 100 mb down to 925 mb.

Notably missing is a structured introduction to charts for specific pressure levels, such as the 500 mb height map. That discussion has been shifted to the appendices. Instead, chapter three focuses on the various factors that the maps depict, and the book makes such liberal use of the different maps by way of illustration that the reader gains familiarity with them through osmosis. My guess is, Tim believes that by helping readers understand upper-air dynamics and processes, the significance and use of the various maps will become apparent through real-world examples.

Chapter five: Surface Analysis–Learn how to read a surface chart, get a basic grasp of air masses, and discover the importance of various boundaries, from cold and warm fronts to drylines and outflow boundaries.

Chapter six: Weather Systems–This chapter groups together concepts from several chapters in the old forecasting handbook. The presentation is logical and fresh. Subjects covered include all-important baroclinic lows and highs, barotropic systems, arctic air outbreaks, and winter weather systems.

Chapters seven and eight deal, respectively, with satellite and radar. Suffice it to say that they are required reading. Since both remote-sensing tools are visual in nature, plenty of pictures are provided to illustrate patterns, systems, outflow boundaries, velocity aliasing, severe weather signatures, and so on.

I’m a bit surprised to see not a single screen grab of a velocity couplet, either in the radar chapter or in the ensuing chapter nine on convective weather. However, velocity products rely highly on a full-color format and don’t lend themselves easily to this book’s black-and-white images. Tim points this out later in figure 9-6, where he writes, “Typical NEXRAD color schemes do not reproduce well in monochrome books.”

Importantly, the chapter on radar discusses the new dual-polarization technology that is being implemented nationwide at the time of this review. Dual-pole is a huge development in the NEXRAD system, probably the biggest stride forward since the deployment of NEXRAD itself.

Chapter nine: Convective Weather–For aspiring storm chasers, this chapter will likely be the Holy Grail of the book. Besides dealing with the ins and outs of thunderstorms, from single-cells to supercells to mesoscale convective systems, this chapter discusses storm-relative winds and introduces another indispensable forecasting tool, the hodograph. Chapter nine moves on to talk about tropical systems including hurricanes.

Chapter ten: Prognosis–This last chapter in the main body of the book deals with the actual process of forecasting. Readers will at this point have recognized that Tim is a strong advocate for understanding not merely how the atmosphere is likely to behave, and where, and when, but also why. Here he discusses the four-part forecasting process. He emphasizes the importance of a hands-on approach to analysis while at the same time recognizing the key role of numerical models, the application, strengths, and weaknesses of which he discusses at length. The chapter concludes with a brief overview of ENSO and teleconnection patterns.

The entire book is amply illustrated. Barely a page exists that doesn’t include some kind of black-and-white chart, map, or photograph. These visual supplements are clear and immensely helpful, to the extent of being integral to understanding much of the written content.

To round things out, the book is peppered with sidebar commentary ranging from the informative, to the philosophical, to the historical, to the humorous. For instance, on page 31 I find a table of NATO color codes; page 57 furnishes a thumbnail discussion of long waves; a lengthy entry on page 120 describes five different empirical forecast techniques; and on page 166, there’s a wry commentary on how to tell whether a tornado is forming using the “thumb tab” approach of the Field Guide to North American Weather.

Appendices

This section is an informational gold mine. Strangely, it’s not even mentioned in the table of contents, so I’m going to give you the breakdown here:

Appendix one: Forecaster’s Guide to Cloud Types–Photos and descriptions of major cloud types, including brief discussions of each one’s significance from a forecasting standpoint.

Appendix two: Surface Station Plots–What all those numbers and symbols mean.

Appendix three: Surface Chart Analysis Procedures–Brief guidelines for doing surface analyses.

Appendix four: Upper Air Station Plots–Similar to the second appendix, except applied to upper air plots.

Appendix five: Upper Air Chart Analysis Procedures–This is about as close to an overview of specific pressure maps as this book provides, which it does from an analysis perspective. This appendix divides into three short sections on upper-, middle-, and lower-tropospheric charts. Between them, they provide insights on the significance, use, and analysis of upper-air maps from 100 millibars all the way down to 925 millibars.

Appendix six: An Isoplething Tutorial–Veteran forecasters invariably are strong advocates of hand analysis, and Tim is a prime example This appendix shows you how to get started at creating your own hand-analyzed weather maps.

Appendix seven: Conversions and Symbols.

Appendix eight: Instability Index Summaries–Brief discussions of the more commonly used forecasting indices such as CAPE, CINH, lifted indices, the energy-helicity index, and the SWEAT index. A couple of these tools–BRN shear and storm-relative helicity–aren’t in themselves related to instability; however they’re so widely used in severe weather forecasting that they require discussion, particularly since they’re factored into such true instability indices as the EHI, STP, and Bulk Richardson Number.

Appendix nine: Types of Thermodynamic Diagrams–Brief discussions and graphic examples of the skew-T/log-P, emagram, Stuve, pastagram, aerogram, and tephigram.

Appendix ten: Blank Diagrams–Reproducible blank skew-T and hodograph.

Appendix eleven: Observation Format Overview–For the incredibly geekish, a quick reference guide to the most commonly used weather-reporting formats: METAR, SYNOP, and TEMP (radiosonde code).

Additional appendix materials without assigned section numbers include the following: suggested reading, software, educational websites, government weather agency websites, and top-ten weather myths.

Three Recommendations

Let me preface my following few critiques by saying that this is a fantastic book. The author is both a veteran storm chaser and an educator, and that combination has inspired him to create a practical resource that is both accessible to lay-persons and helpful to operational forecasters. Storm chasers and anyone who wants to develop skill at weather forecasting would do well to put it in their library.

This said, I have three comments that Tim may wish to consider at some point:

• I liked the old handbook’s quick, specific introductions to the 200/250/300 mb, 500 mb, 700 mb, 850 mb, and surface charts. The overviews of those charts gave me–at a time when I was a complete novice and needed weather knowledge delivered to me in brick form–an instant, systematized reference to the constant-pressure maps that are such essential tools of the trade.

Granted, entire books have been written about weather maps, including Tim’s own Green Book, the Weather Map Handbook. The new Weather Analysis and Forecasting Handbook is obviously not intended to fill such a role. But perhaps in the appendix section, the fifth appendix could be fleshed out a bit by providing a top-down sampling of CONUS maps for a single date/time. That way those unfamiliar with upper atmospheric maps could see how, say, March 13, 2011, at 1200 UTC mapped out at 300 mbs, 500 mbs, 700 mbs, 850 mbs, 925 mbs, and on the surface.

• Granted the limitations of trying to translate something as color-dependent as radar velocity products into a gray-scale format, there may nevertheless be a benefit to making the attempt. I say this because the ability to recognize storm-relative velocity couplets is so critical in storm chasing. While the illustrations on page 145 (figs. 8-2a–f) do a good job of conveying the general idea, there’s nothing like real-life examples. Perhaps such examples could be included in the future, whether directly in the book or possibly as a link to a page featuring radar screen captures on Tim’s Weather Graphics website.

• A quick, easy-reference glossary of essential terms would be a welcome addition.

With these three suggestions on the table for Tim to consider in his next edition, I unhesitatingly recommend this book. It’s superb, a labor of love by one of the gurus of operational forecasting who clearly cares a great deal about helping others learn the ropes.

Some months back, I reviewed Tim’s other recent publication, Severe Storm Forecasting. It’s another excellent resource for storm chasers in particular, covering some of the same ground as this book and expanding considerably on the subject covered in chapter nine, “Convective Weather.” Good as that book is, though, Weather Analysis and Forecasting provides the more complete, well-rounded picture. Be forewarned: it’s not a book you will read and absorb in one sitting. It is chewy material that will require you to approach it analytically and patiently. This is a resource you will pull off the shelf again and again, whether to re-engage with material you’re still trying to grasp or to refresh yourself on concepts you’re already familiar with.

Purchasing Information

- Weather Forecasting and Analysis by Tim Vasquez, 260 pages.

- $29.95 plus shipping, available from Weather Graphics.

NOTE: This is a non-paid review. I’ve written it as a service to my readers and to Tim because, having read the book, I’m convinced of its value for storm chasers and severe weather buffs.