Until early yesterday morning, I was pretty certain that I wasn’t going to be chasing yesterday’s squall line associated with the record-breaking low pressure system that’s moving across the Great Lakes. With storms ripping along at 60 knots, what kind of chasing is a person going to do?

Then came the 7:00 a.m. phone call from my chase partner, Bill Oosterbaan, informing me that the Storm Prediction Center had issued a high risk for the area just across the border in Indiana and Ohio. With the rapidly advancing cold front still west of Chicago, we’d have ample time to position ourselves more optimally. This would be an early-day storm chase. It would also almost surely be our last chase for the next four or five months. What did we have to lose?

I hooked up with Bill at the gas station at 100th St. and US-131, and off we went. The storms had moved into Chicago by then, and as we dropped south, it became apparent that we would also need to break east and then stairstep down into Ohio, buying time in order to let the line develop with daytime heating. Satellite showed some clearing in Ohio,

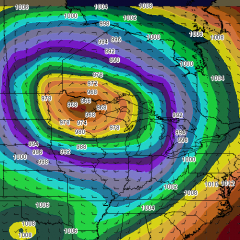

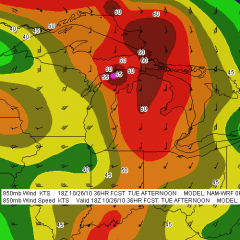

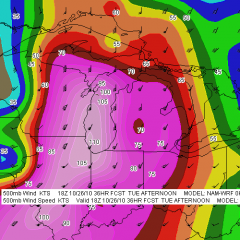

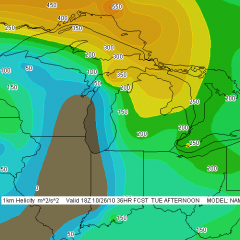

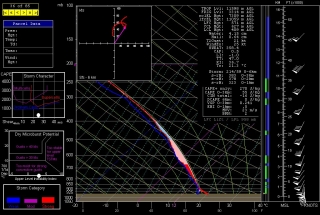

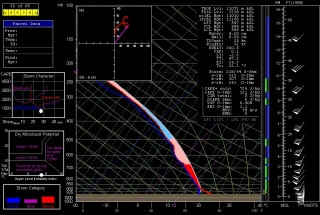

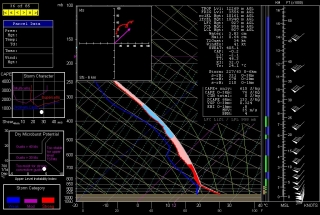

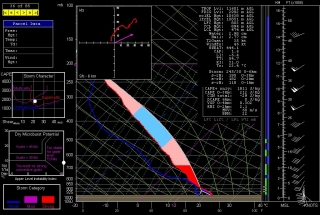

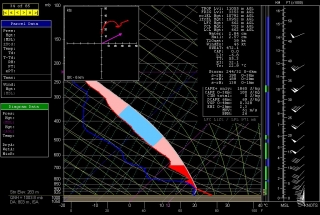

suggesting a better chance for instability to build. Catching I-94 in Kalamazoo, we headed east toward I-75, with the Findlay area as our target.Off to the northwest in Minnesota, the low was deepening toward an unprecedented sub-955 millibar level, sucking in winds from hundreds of miles around like the vortex in an enormous bathtub drain. Transverse rolls of stratocumulus streamed overhead toward the north, indicating substantial wind shear. (Click on image to enlarge.)

By the time we crossed the border into Ohio, tornado reports were already coming in from the west as the squall line intensified. Soon much of the line was tornado warned. However, while the warnings were no doubt a godsend for a few communities that sustained tornado damage yesterday, they weren’t much help to Bill and me. Chasing a squall line is different from chasing discrete supercells.

We had in fact hoped that a few discrete cells would fire ahead of the line. But the forecast CAPE never materialized to make that happen, and we were left with just the line. In that widely forced environment, tornadoes were likely to occur as quick, rain-wrapped spinups rather than as the products of long-lived mesocyclones. Even with GR3, the likelihood of our intercepting a tornado would require a high degree of luck. It was harder to identify areas of circulation with certainty; I found myself using base velocity as much as storm relative velocity on the radar, and comparing suspect areas not with easy-to-see hook echoes in the reflectivity mode, but with kinks in the line. It was pretty much a game of meteorological “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.”

North of Kenton, we headed west and got our first view of the squall line. For all the hooplah that had preceded the thing, it didn’t appear very impressive. Just your average storm front–much windier than most, but also a bit anemic-looking compared to some of the shelf clouds I’ve seen. Still, it was a lovely sight, watching those glowering clouds grope their way across the late-October farmlands.

.

Neither of us was quite ready to end the chase, so with the storm rapidly closing in, we scrambled back into the car and stairstepped to the southeast in the hope of intercepting a likely-looking reflectivity knot that had gone tornado-warned. It was fun playing tag with the storm, driving through swirls of leaves spun up by the outflow. But there really wasn’t much incentive for us to continue the game indefinitely. Eventually we turned back west and drove into the mouth of the beast.

For a few minutes, we got socked with torrential rain and some impressive blasts of wind (and, I should add, absolutely no lightning or thunder whatever). Then it was over. Time to head home.

In Kenton, we grabbed dinner at a small restaurant. Then we headed toward Cridersville, 28 miles straight to the west next to I-75, where there had been a report of “major structural damage” from a tornado. The report was accurate. A small but effective tornado had torn through the community, uprooting and snapping off large trees, taking off roofs, and demolishing at least one garage that I could see. Of course we couldn’t get into the heart of the damage path, but a few passing glimpses suggested that some of the damage may have been fairly severe.

As I said at the beginning, this chase will likely have been my last of the year. I never know for sure until the snows fly, but it seems like a pretty safe bet that I won’t be heading out again after storms until March or April. It’s hard to call this chase a bust since our expectations weren’t all that high to begin with. Plus, tornadoes or no tornadoes, it was an opportunity to engage with a historical weather system. Like other significant weather events such as the Armistice Day Storm and the 1974 Super Outbreak, this one will be given a name in the annals of meteorology. Me, I’m calling it the Great Lakes Superbomb of 2010. In a number of ways, it hasn’t proved to be as impactful as was forecast, but it’s not over yet. And regardless, I’m glad I got the chance to get out and enjoy a final taste of synoptic mayhem.

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.