Now, while my video from Friday’s chase is uploading to YouTube, is a good time for me to write my account of how things transpired down in southern Indiana.

The phrase “historic event” rarely describes something good when applied to severe weather. March 2 may qualify as a historic event. The current NOAA tally of tornado reports stands at 117; the final number, while likely smaller once storm surveys have been completed and multiple reports of identical storms have been consolidated, may still set Friday’s outbreak apart as the most prolific ever for the month of March. Whether or not that proves true, Friday was unquestionably a horrible tornado day that affected a lot of communities from southern Indiana and Ohio southward.

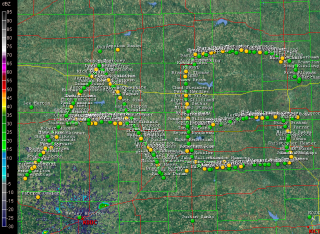

The Storm Prediction Center did an excellent job of keeping track of the developing system, highlighting a broad swath of the eastern CONUS for a light risk in the Day Three Convective Outlooks and upgrading the area on Day Two to a moderate risk. On Day One, the first high risk of 2012 was issued for a four-state region that took in southern Indiana and southwest Ohio, most of Kentucky, and north-central Tennessee–a bullseye in the middle of a larger moderate risk that cut slightly farther north and east and swept across much of Mississippi and Alabama as well as northwestern Georgia.

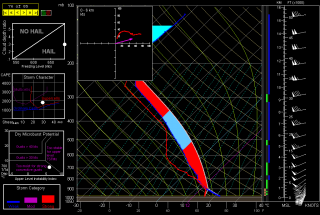

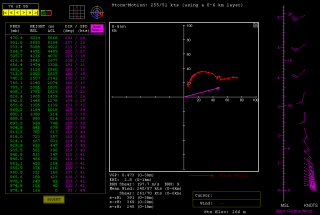

The SPC and NWS offices weren’t the only ones keeping vigilance. Storm chasers across the country were watching the unfolding scenario, among them being my good friend Bill Oosterbaan and me. Here are the February 29 00Z NAM model sounding and hodograph for March 2, forecast hour 21Z, at Louisville, Kentucky. (Click on the images to enlarge them.) With MLCAPE over 1,800 J/kg, 0-6 km bulk shear of 70 knots, and 1 km storm-relative helicity at 245 m2/s2, the right stuff seemed to be coming together. By the time the storms actually started firing, those figures were probably conservative, particularly the low-level helicity, which I recall being more in the order of 400 m2/s2 and up. Simply put, the region was going to offer a volatile combination of moderate instability overlaid by a >50-knot low-level jet, with a 100-plus-knot mid-level jet core ripping in.

I had my eyes set on southeastern Indiana. The problem with that area is, it’s lousy chase terrain along the Ohio River, and it doesn’t improve southward. If there was an ace-in-the-hole, it was Bill’s knowledge of the territory, gleaned from his many business trips to Louisville.

We hit the road at 7:15 that morning, stopping for half an hour in Elkhart so Bill could meet with a client and then continuing southward toward Louisville. Bill was of a mind to head into Kentucky, where the EHIs and CAPE were higher; I was inclined to stay farther north, closer to the jet max, the warm front, and, presumably, stronger helicity. But either choice seemed likely to furnish storms, and since Bill was driving, has good instincts, and knows and likes western Kentucky, I was okay with targeting the heart of the high risk rather than its northern edge.

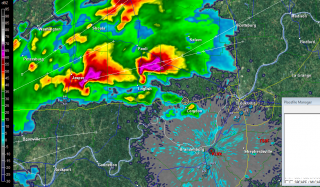

But that plan changed as we drew near to Louisville. By then, storms were already firing, and one cell to our southwest began to take on a classic supercellular appearance. Bill was still for heading into Kentucky at that point, but after awhile, a second cell matured out ahead of the first one. We now had two beautiful, classic supercells to our southwest, both displaying strong rotation. It was a case of the old adage, “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”–except in this case, there were two birds, back to back. And I-64 would give us a clear shot at both of them.

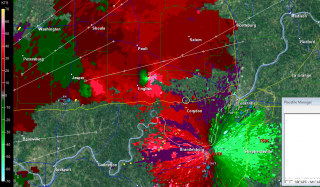

So west we went, and into chase mode. At the Corydon exit, we caught SR 135 north, headed for an intercept with the first supercell. The two radar captures show the base reflectivity and SRV shortly after we began heading up the state road.

A few miles south of Palmyra, we got our first glimpse of a wall cloud maybe four miles distant. That’s all there was at that point, and the hilly, forested terrain afforded less-than-optimal viewing. Within a minute or two, we emerged into an open area just in time to see a funnel descend from the cloud. Tornado!

The sirens were sounding in Palmyra, providing an eldritch auditory backdrop to the ropy funnel writhing in the distance as we drove through town. The tornado went through various permutations before expanding into a condensation cone revolving like a great auger above the treeline. It was travelling fast–a good 60 miles an hour, at a guess. As we sped toward it, the condensation hosed its way fully to the ground and the tornado began to broaden. It crossed the road about a half-mile ahead of us, continuing to intensify into what appeared to be a violent-class tornado with auxiliary vortices wrapping around it helically.

Shortly after, Bill and I came upon the damage path. We pulled into a side road lined with snapped trees, amid which a house stood, somehow untouched except for a number of peeled shingles. The tornado loomed over the forest beyond, an immense, smoky white column wrapping around itself, rampaging northeastward toward its fateful encounters with Henryville and Marysville.

The time was just a few minutes before 3:00 eastern time. While I prepared and sent a report to Spotter Network, Bill turned around and headed back south. We had another storm to think about, and it was closing in rapidly. It wouldn’t do to get caught in its way.

Back in Palmyra, we headed west and soon came in sight of another wall cloud. This storm also reportedly went tornadic, but it never produced during the short time that we tracked with it. We lost it north of Palmyra; given the topography, the roads, and the storm speed, there was no question of chasing it.

From that point, we headed south across the river into Kentucky to try our hand at other storms, but we saw no more tornadoes, nor, for that matter, much in the way of any serious weather. Not that there weren’t plenty more tornado-warned storms; we just couldn’t intercept them, and after giving it our best shot, we turned around and headed for home.

Lest I forget: my worst moment of the chase came when I couldn’t locate my video of the tornado in my camera’s playback files. It seemed unfathomable that I could have horribly botched my chance to finally capture decent tornado footage with my first-ever hi-def camera. After being miserably sidelined during last year’s record-breaking tornado season, the thought that I had somehow failed to record this day’s incredible intercept just sickened me. Fortunately, there were no sharp objects readily available; and better yet, the following morning I discovered that I had simply failed to scroll up properly in the playback mode. All my video was there, and it was spectacular. Here it is:

My excitement over the video was offset by reports of just how much devastation this tornado caused eighteen miles northeast of where it crossed the road in front of Bill and me. Henryville, obliterated. Marysville, gone. Eleven lives lost in the course of that monster’s fifty-two-mile jaunt. And similar scenarios duplicated in other communities across the South and East. The death toll for the March 2 outbreak presently stands at around forty.

In the face of a mild winter and an early spring, Friday was the inauguration for what may be yet another very active severe weather season east of the Mississippi. We can only hope that there will be no repeats of last year’s wholesale horrors. May God be with those have lost loved ones and property in Friday’s tornadoes.

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel.

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel. color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.

color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.