Tornado season is now long past, and the sting of missing great storms either through bad targeting or having to head home one and two days before two major events has eased. Maybe next year will be better. Besides, the show’s not over till the snows fly.

Meanwhile, I’m looking back to my most interesting chase of the year, documented by the video at the bottom of this post. Ironically, I logged around 6,000 miles to and from Oklahoma and Kansas with little to show for it, while my humble backyard of Michigan gave me an enjoyable and productive bit of action.

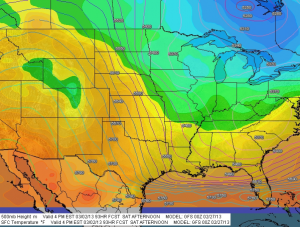

On May 28, a warm front lifted up through lower Michigan, ushering in decent moisture and instability along with a good boundary for them to work their mojo with. The thing that seemed to be missing was adequate shear for storm organization–but I ignored conditions farther east of me. I just didn’t take the setup seriously enough, and when Kyle Underwood, the WOOD TV8 meteorologist, inquired which of the TV8 chasers planned to head out, I said that I didn’t see much potential. If something came my way, I would grab it, but otherwise, I didn’t want to waste gas. That was understandable: money was tight, and I planned to chase in Kansas the next day. Still, geeze, what an idiot (me, not Kyle).

Let us pause momentarily while I give myself a retroactive dope slap. I have come to a conclusion: in Michigan, when a warm front shows up with good CAPE present and any kind of bulk shear to speak of, even anemic bulk shear, chase the front. Never mind what the models have to say about storm-relative helicity; helicity will take care of itself if a storm manages to organize in the vicinity of the frontal boundary. Just get out there and chase the stupid front. Particularly farther to the east. Storms in Michigan often have a way of intensifying and organizing near and east of I-69 and, north of Lansing, US-127.

That was the case on this day. My first clue was when I glanced at the radar later and noticed that Kurt Hulst was on a storm off to the southeast. Kurt knows what he’s doing, and the storm looked decent–in fact, it was tornado-warned. Okay, I thought, I missed that one. Probably it’ll be the only one. So I sat tight and watched the radar as other storms formed. They looked like a convective mess to my west, but they clearly were moving into a better environment as they progressed east. Finally, I’d had enough. I grabbed my laptop and cameras and headed out.

I locked onto the most intense-looking cell in my vicinity and tracked with it toward Portland. But another was following on its heels, and given the way that the storms were behaving, I thought I’d be better off dropping the one I was on and letting the new one come to me. Presumably, it would get its crap together on the way, and that is what happened.

As it approached Grand Ledge just west of Lansing, this storm developed a most amazing streamer of scud sucking into its updraft base from the east. It appeared to originate near ground level–hard to tell with trees constantly interrupting the view–and rocketed toward the storm, leaving no doubt that this storm had impressive inflow.

Driving into Grand Ledge, I found myself under the area of rotation, with crazy, low cloud motions. Turning around, I headed back north and parked by the airport, then watched and filmed as the storm headed east into Lansing. It looked very close to spinning up a tornado; in the video, you can see it trying hard, and eventually it succeeded.

But I had to drop the chase. My friend Steve Barclift and I planned to chase the next day in Kansas, and I had to meet him so we could hit the road for the long drive west. As it turned out, the storm I was on provided a better show than anything we saw along the dryline. My buddy Rob Forry managed to catch this storm at its tornadic phase and got some nice video.

My original hi-def shows the motion of the inflow streamer nicely as I enter Grand Ledge. Regrettable, this YouTube clip doesn’t render the details as well, but you’ll at least get a feel for the motion. The storm was an interesting one and fun to chase. It would be nice to get another one like it. It’s only August, so the door is far from closed.