Welcome to tornado season 2012. It’s a reception that anyone but a storm chaser would no doubt prefer to decline, but there’s no getting around it. This abnormally warm March has already produced one prolific and deadly outbreak as well as several lesser tornado events. The Gulf conveyor is open for business, shuttling rich moisture into large sections of the continental United States, and with one system after another moving across the heartland, we appear to be moving into another active spring.

So let’s talk about what it will take to survive. If you’re a storm chaser, a National Weather Service or media meteorologist, or someone involved in emergency management, you can skip this post as it’ll be preaching to the choir. But if you’re the average John or Jane Doe, listen in:

On days when severe weather is imminent, YOU are responsible for remaining alert as if the lives of you and your family members depend on it–because that could very well be the case.

After virtually every tornado disaster, some survivor invariably repeats the age-old mantra, “We had no warning.” Journalists love it. Someone–the National Weather Service, emergency management, or somebody somewhere entrusted with safeguarding the public–failed to warn an unsuspecting community of looming danger. Once again, those charged with protecting lives and property failed miserably.

It makes great press, but it’s rarely true today. There are exceptions–the outrageous warning dereliction on the part of Saint Louis International Airport officials on Good Friday of last year comes to mind. Most of the time, though, the real problem is one of two things, or both:

- * people didn’t receive a warning in the manner they believed it should have come to them; or

- * they failed to take seriously the warnings that were issued.

Let’s consider each of these concerns.

People’s expectations of how they will be warned don’t match the reality of how warnings are disseminated.

.

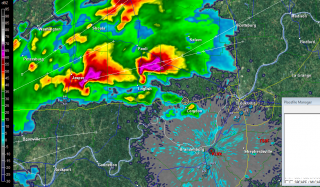

I’ll preface the following discussion by saying that I am no operational forecasting expert. My knowledge is that of a layman, albeit an informed one, a storm chaser of over fifteen years’ experience, including, for the past year, serving as a media chaser for WOOD TV8. With that caveat dispensed with, let me begin by saying that virtually no significant severe weather event escapes the notice of the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) or National Weather Service (NWS) meteorologists. I’m not referring to rogue episodes that confound even the experts. Unforecastable events such as last week’s three tornadoes in eastern Michigan may have a devastating local impact, but they’re not in the same league as classic tornado outbreaks, which are preceded by conditions that meteorologists are able to monitor long before they ever mature. Potential severe weather events are normally scrutinized days in advance, and broadcast media such as The Weather Channel begin talking about them well ahead of time.

Big weather is invariably well-forecasted weather; the question is whether people pay attention to the forecasts. As a severe event moves toward day one, warning meteorologists do their utmost to heighten public awareness. With the advance of social media, weather watches and warnings go out through a wider variety of means than ever–TV, local radio, NOAA weather radio, civil defense sirens, Twitter, Facebook, media websites, and more. All that can be done is being done to disseminate timely, life-saving information to as many people as possible. Moreover, in a day when funds continue to be cut from its budget, the NWS continually strives to improve its warnings. The people there take their role as weather guardians very seriously.

The rest is up to the public. That’s you. It’s a matter of personal responsibility.

On days when severe weather is forecast–particularly when your area lies in or near a moderate or a high risk, and above all when a PDS (Particularly Dangerous Situation) has been issued–it is critically important that you maintain situational awareness.

If a credible source repeatedly warned you that your house was being targeted for a robbery one or two days hence, would you go about your life as usual when the day arrived? Of course not. You would be in a state of heightened alert and ready to take immediate action. That should be your stance on severe weather days. A tornado can take more from you in seconds than a whole busload of thieves can in an entire afternoon.

Don’t count on the tornado siren to sound. It may not if the power grid has been knocked out. Or you may not hear it if you’re too far away from it, or if it’s 3:00 a.m and you are sound asleep. Even if you hear the siren, you may not respond to it appropriately if you live in an area that gets warned frequently, to the point where residents have grown jaded from warning burnout. In any case, a civil defense siren is only one means of receiving warnings, and–take note–you should not depend on it as your primary source. Watch your local TV station, or check out their website, their Facebook updates, or their Twitter feeds. Or tune in to local radio. You have more warning options available to you today than ever before. Make use of them.

A NOAA WEATHER RADIO SHOULD BE AS STANDARD IN YOUR HOME OR OFFICE AS SMOKE ALARMS.

IF YOU DON’T HAVE ONE, GET ONE.

It’s 2:00 a.m., and you and your family are sound asleep. Throughout the day, TV meteorologists had been forecasting impending severe weather after dark, and later in the evening, a steady stream of severe thunderstorm and tornado warnings began to interrupt the programming. With your town lying on the eastern side of a tornado watch, you were concerned enough that you thought you’d remain awake for a while after everyone else went to bed, just in case.

But by midnight, the warnings were still off to your west by several counties. It was late, and you needed to be at work at 8:00 a.m. “Besides,” you told yourself, “nothing ever happens around here.” As you headed to bed, you noticed lightning flickering in the distance through the window, but it was still a long way off.

Now, two hours later, you and your family are all sleeping soundly as a violent, half-mile-wide tornado grinds across your neighborhood toward your house. You won’t be going to work in the morning after all.

Don’t let it happen. Outfit yourself with a weather radio. It’s one of your best weather-warning assets any time of day, and at night it’s your only line of defense. It can make a life-or-death difference for you and your loved ones.

Many people don’t take warnings seriously.

.

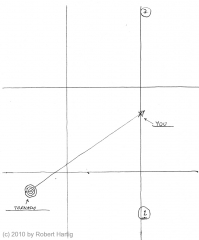

When the siren sounds, take cover. When the broadcast meteorologist or the weather radio tells you to seek shelter, do so. Unless you’re knowledgeable about how storms behave and have an informed grasp of exactly what the weather is doing relative to your location, head immediately for safety. Don’t go outside and gawk at the sky. Far too many tornado victims become statistics because they want to take a look before they take action. But tornadoes can materialize in seconds, and ones that are in progress can descend on you as swiftly as a hawk on a rabbit. While some may move at a turtle’s pace, others, particularly those in the early spring, may be racing along at 60 or 70 miles an hour or even faster. By the time your untrained eyes have informed you that you need to seek shelter, it may be too late. So don’t waste time–go to the basement or whatever safe place you’ve earmarked for severe weather. You do have such a place in mind, right? If not, take some time to plan where you’ll go.

Do not ignore warnings. Maybe you live in a place where you’ve gotten a lot of warnings that never materialized. The siren sounded time and again, but nothing happened. The warnings on TV and radio were all Doppler-based, containing language like, “A storm capable of producing a tornado is moving toward …” No matter. Take every warning seriously. Otherwise, the warning you ignore will be the one you’ll wish you had paid attention to.

Warning meteorologists are caught in a double-bind when it comes to radar-based warnings. When mets issue warnings based on radar-indicated circulation, they get accused of crying wolf when nothing happens. But if they fail to issue warnings because they lack ground proof, that’s when a tornado will drop out of the sky and wipe out a neighborhood, and the residents will complain that they had no warning.

Damned if they do and damned if they don’t: that’s the no-win scenario that warning meteorologists have to deal with. Since they are more concerned with protecting you and your family than they are with upholding their image, and since they are very good at interpreting radar data in the light of environmental conditions, they will rather play it safe than sorry. But the NWS and SPC, which continue to explore technological and sociological ways to improve the warning system, can only do so much; and your local broadcast meteorologists can only do so much. The rest is up to you.

Your safety is in your own hands.

.

It’s up to you to take warnings seriously and respond to them promptly. On days when severe weather has been forecast, it’s up to you to maintain a level of alertness that will enable you to take life-saving action even if you never hear a siren, see a warning on TV, or receive a tweet on your smartphone.

This year, more people are going to die in tornadoes. Some of the deaths may be unavoidable. When a large, violent tornado moves through a heavily populated area, as happened last year in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Joplin, Missouri, fatalities will sometimes occur even when people do everything right. But most deaths will be ones that could have been avoided had people taken proper precautionary actions.

Pay attention to the weather that is shaping up for your area days in advance. Equip yourself with a dependable means of receiving weather updates, including a weather radio for your home that can sound an alert 24/7. Take every warning seriously, respond to it immediately, and remain in your place of safety for as long as necessary.

THE RESPONSIBILITY IS YOURS. STAY SAFE THIS TORNADO SEASON.