Okay, sax players and jazz soloists, I haven’t forgotten you! I’ve been quite focused on the weather recently, but I’ve also been practicing my horn pretty industriously, and, in the words of the old pop classic, you were always on my mind.

It’s high time I wrote a musical post. This one ought to give you a little something to thrash with. The bit in the headline about “implied polyrhythms” sounds impressive, but I’m not sure it’s entirely accurate. I just don’t know what other term to use–I don’t think “hemiola” is quite right. So we’ll go with “polyrhythm” for the sake of having some kind of handle of nomenclature with which to pick up our suitcase of application.

The concept itself is simple: by taking a pattern that normally lays well in triplets and recasting it in eighth notes, or vice-versa, you automatically rearrange the way that certain notes are accented. The result is usually some pretty cool syncopation that will grab your listeners by the lapels, throttle them into submission, and make them hand over their wallets. Well, okay, nothing that dramatic, but it should certainly get their attention.

Since your eyes and ears will explain to

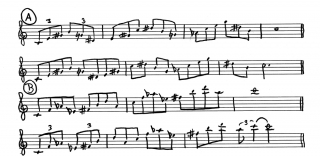

you what I mean better than my words can, to your right you’ll find a couple of examples. Click on the image to enlarge it, then print it out and take it with you to the woodshed.The first line of example A features triplet arpeggios on the augmented scale. The following line uses exactly the same note order, but converts it to eighth notes.

Example B shows you how the concept works in reverse, taking a simple sequence of fourths in duple meter and converting it to triple meter.

The result is hipness, pure and unmitigated.

Experiment with this concept. And don’t limit yourself to just triplets and eighth notes. You can reframe any odd grouping of notes into eighth notes or sixteenth notes, and the converse also applies. The practice of translating one meter into another is no mystery, and if you’ve been playing the sax for some time, you’re probably already an old hand at doing so. It’s a nice way to spice up your improvised solos with rhythmic energy.

That’s all for tonight. There’s a bottle of Double Crooked Tree Imperial IPA sitting in the fridge, and its siren song is too powerful for me to ignore any longer. For more articles on jazz improv, including exercises and transcribed solos, visit my jazz page.