You’re looking at the Henryville, Indiana, high school, photographed from across the street on September 30, 2014. By all appearances, there’s nothing remarkable about it. But if you’re aware of its recent history, then you know differently. Two and a half years ago, on the evening of March 2, 2012, there wasn’t much left of this building or, for that matter, a good part of Henryville. Roaring out of the southern Indiana hills and across I-65 to the west shortly after three o’clock that afternoon, a large tornado inflicted EF-4 damage in this small community, leveling much of the school and residences east of it.

You’re looking at the Henryville, Indiana, high school, photographed from across the street on September 30, 2014. By all appearances, there’s nothing remarkable about it. But if you’re aware of its recent history, then you know differently. Two and a half years ago, on the evening of March 2, 2012, there wasn’t much left of this building or, for that matter, a good part of Henryville. Roaring out of the southern Indiana hills and across I-65 to the west shortly after three o’clock that afternoon, a large tornado inflicted EF-4 damage in this small community, leveling much of the school and residences east of it.

Like many a tornado-ravaged town, Henryville pulled together, took care of its own, and rebuilt. Today, the resilient spirit of its citizens shows not in any marks of the devastation that transpired there that afternoon but by the lack thereof. Where piles of  debris once lay, new houses and commercial buildings have sprouted. The school is in full sway, with new buildings in place of the ones flattened by the storm. The only evidence I could see that Henryville is a tornado town–and the clue is noticeable, chiseled into the landscape–is a swath of shattered trees where the wind blasted the hillside east of the school. That memento left by the town’s dark visitor is not soon expunged.

debris once lay, new houses and commercial buildings have sprouted. The school is in full sway, with new buildings in place of the ones flattened by the storm. The only evidence I could see that Henryville is a tornado town–and the clue is noticeable, chiseled into the landscape–is a swath of shattered trees where the wind blasted the hillside east of the school. That memento left by the town’s dark visitor is not soon expunged.

On Tuesday the 30th, I made a side trip through Henryville on my way down to Clarksville, just north of the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. I and my friend and long-time chase partner, Bill Oosterbaan, had been asked to do an interview with Karga 7, a production house for The Weather Channel, for a show spotlighting the Henryville tornado. A couple months ago, Nichole, a producer with Karga 7, contacted me to inquire about using my footage of the tornado, which Bill and I had caught at its formative and maturing stages north of Palmyra, Indiana. I directed her to my video broker, Kendra Reed of KDR Media, and Kendra negotiated agreements for Bill and me, and now here I was, heading down I-65 toward Clarksville’s Clarion Hotel, where the interview was to be held.

I felt both pleased and nervous at the prospect of being featured on national media. I’m a low-key kind of guy, and while, as a professional wordsmith, I can communicate colorfully and descriptively when I need to, I’m not by nature a showcase personality. So I wasn’t sure what kind of interview material I’d make. Writing allows me to edit my words till they reflect my thoughts to my own satisfaction, but an interview doesn’t afford that luxury. I hoped to shed a realistic and positive light on storm chasing and chasers, neither of which I think the public understands very well; and I wanted to give a strong message for people to take personal responsibility for their own safety and that of their loved ones by paying close attention to severe weather forecasts and warnings and not depend on sirens.*

Nichole, her two camera persons, and the guy who greeted us at the door seemed like great people. They were professional, courteous, and enjoyable to work with. The actual interview lasted at least an hour and a half, and I think Bill and I did a good job answering the questions, playing off of and supplementing each other’s responses. In a couple instances, our answers differed. For instance, Nichole asked, “Did you know when you first saw it that this was a killer tornado?” I said no. We had caught the funnel at its inception and stayed with it through early maturity, and I felt comfortable saying it was a violent and potentially lethal tornado; however, “killer tornado” isn’t about storm strength but verified human impact, something quite different. All tornadoes have the potential to kill, but most don’t, and that includes the relatively few violent ones. Not until later would I learn of this storm’s heartbreaking toll on New Pekin, Henryville, and Marysville.

Bill said yes, but he had processed the question differently from me. He does business frequently in nearby Louisville and knows the area. He was aware of towns to the northeast that the tornado might impact, and he knew it could cross an interstate highway. Bill evidently felt comfortable with calling the tornado a killer at the onset, based on its violence. It boils down to a matter of how each of us interpreted the question. I think he and I would agree that neither of us knew what the storm was going to do, but we did know what it could do if it hit a community, and we very much hoped that wouldn’t happen.

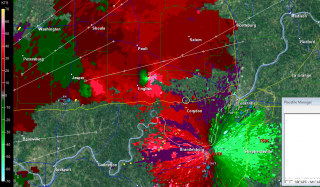

Between Bill and me, I think we did a good job of communicating two messages: (1) the tension storm chasers experience between their passion for storms as the magnificent forces of nature they are versus the concern we feel for those who lie in harm’s way; and (2) the excellence and limitations of severe weather warnings, and the need for people to be proactive in safeguarding themselves against violent weather. I hope those messages will come across clearly in our part of the TWC episode. We did our best, and from here, our content rests in the hands of the film editors. I look forward to seeing how it all turns out. Interview aside, the footage Bill and I got of the tornado was spectacular and affords a unique perspective of the tornado. I chalk that up to good forecasting, serendipity, and Bill’s knowledge of the area.

On March 2, 2012, Bill and I had been chasing together for sixteen years, beginning well before technology improved the odds of seeing tornadoes. We had logged thousands of miles, busted many a time, gradually improved our forecasting skills, seen some amazing storms, and had a blast overall. The thing that kept us going was, and remains, sheer love for the storms, not money or media attention. But it’s nice to think that a little of both has finally come our way. Many thanks to Kendra Reed for her invaluable role in negotiating with Karga 7. Kendra, you are the absolute best!

The show will air this coming spring, probably sometime in April.

__________

* Civil defense sirens are the least dependable of warnings. When tornado victims say they “had no warning,” what they often mean is that the sirens weren’t sounded. I’ll reiterate here what I said in the interview: don’t count on sirens. They may or may not sound, depending on the judgment of your local civil defense; and if they do sound, you might not hear them for various reasons. Sirens are of limited effectiveness, and to rely on them as your primary warning is to live in the last century and jeopardize your safety. Today’s warning system harnesses everything from local television to mobile phones to social media and more, and while it’s still possible for the occasional rogue tornado to slip in under the radar, the big storm systems such as the one on March 2, 2012, are invariably well-forecast and well-warned.