There are times when the sight of a high risk sickens rather than excites me, and Saturday was one of those days. It’s one thing when severe storms occur in the Great Plains where the population is sparse, but when a swarm of tornadoes roars across an area punctuated with cities and towns, all I can think is, “Oh no. All those people!” Such was the case with last week’s horrendous three-day tornado outbreak across the South and East.

The outbreak commenced Thursday in Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas, with a preliminary figure of 27 tornadoes reported.* The action ramped up Friday in Louisiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Illinois, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, with an initial tally of 120 tornadoes. Day three was the worst of all, with yet another 120 reported tornadoes slashing across the populous, densely forested Southeast and East from South Carolina to as far north as Pennsylvania. Hardest hit was North Carolina, where large and powerful tornadoes ripped through Raleigh and other communities. Twenty-two lives were lost, 11 of them when a three-quarter-mile-wide, EF3 monster carved a 19-mile path across Bertie County. Another six died in Virginia. And in its previous two days, the outbreak claimed seven lives in Arkansas, seven in Alabama, two in Oklahoma, and one in Mississippi.

In all, Saturday’s tornadoes were North Carolina’s most lethal since 1984, when 42 died. And regionally, Friday and Saturday were the worst tornado outbreak in the Southeast since the Super Tuesday Outbreak of February 5–6, 2008, when 87 tornadoes killed 57 people in four Dixie Alley states.

But my point in writing this article isn’t to provide yet another news story on the disaster. Rather, it’s to share my feelings as I watched it unfold. With some truly amazing video coming in from chasers in Oklahoma, the first day was fascinating. Day two, watching tornadic supercells crawl across Mississippi and Alabama on the radar was unnerving; I hoped nothing bad would happen down there in the South, but I knew better. On day three, when I saw the high risk go up in North Carolina, my heart sank.

When it comes to armchair chasing, I’m moderate in my habits. If I can’t actually be out chasing, I often opt for a more constructive use of my time than watching the radar and gnawing my knuckles. This time, though, I couldn’t help watching. At first the line of storms looked mean but not terribly alarming. As the storms headed east, though, they began to organize and strengthen, and circulations began to show on radar. Strong circulations, a whole line of them, stretching from northern South Carolina up into Maryland and Virginia. And the tornado reports began filtering in. These storms didn’t merely appear to be impacting towns–they were.

I watched one monster chew through Raleigh, thinking, “No way!” Then came the videos on YouTube, one of them by chasers at unnervinglyclose range, and I knew. No one was dodging the bullet this time. Neighborhoods were being pulverized and people were dying.

With fiscal conservatives recently wanting to slash the budget of the National Weather Service, all one has to do is witness a scenario like last weekend’s in order to realize the supreme lunacy of such a move. Tornado season is just getting started. More is on the way. Bad as last week was, we could yet see worse. How smart is it to pull the rug out from under our national weather warning system at precisely the time of year when its optimal service is most needed?

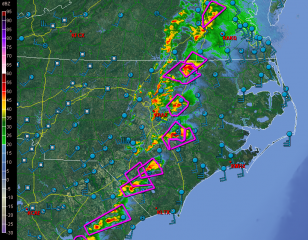

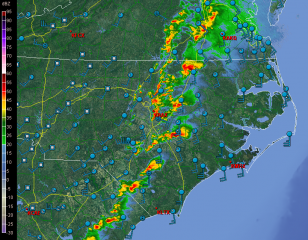

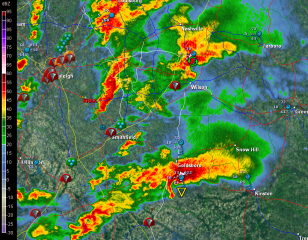

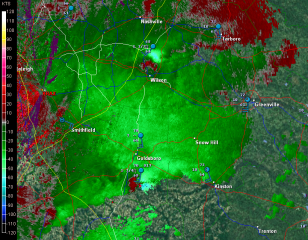

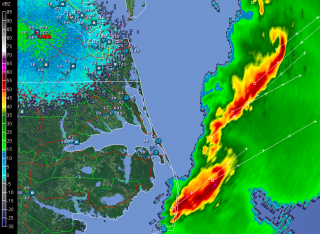

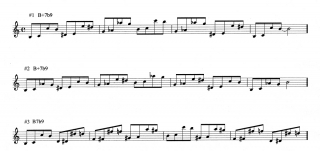

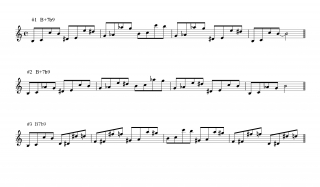

But I digress. Here are a few GR2AE radar grabs of the North Carolina supercells. Storm motions were to the northeast. The rest tells its own story if you know what you’re looking at.

First, here’s are a couple macroscopic views.

Next, I’ve zoomed in on the Raleigh radar to cross-check reflectivity and storm-relative velocity on a couple supercells.

The final image was taken after the storms had moved out to sea. It shows a couple of northern line-end vortices that I found interesting and thought you might too.

____________________

* All numbers reflect preliminary reports at the time of this post’s publication. Final statistics will likely be different.