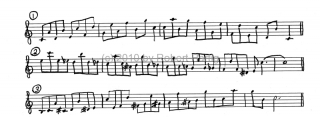

Yesterday I published an etude that I wrote based on the chord changes to the Jamey Aebersold tune “Round About.” The tune is included in the second CD of the 2-CD set Dominant Seventh Workout (number 84 ins the Aebersold jazz improvisation CD series).

Since my instrument is the alto saxophone, it was natural for me to write the etude using the Eb transposition. But of course, the whole world doesn’t play Eb instruments. So I promised those of you who play tenor sax, trumpet, flute, and other Bb and concert pitch instruments that I would provide transposed charts for you.

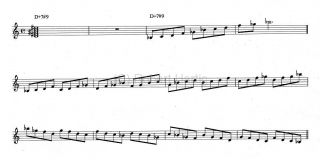

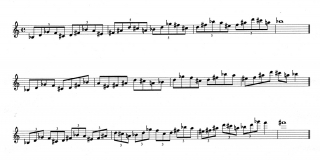

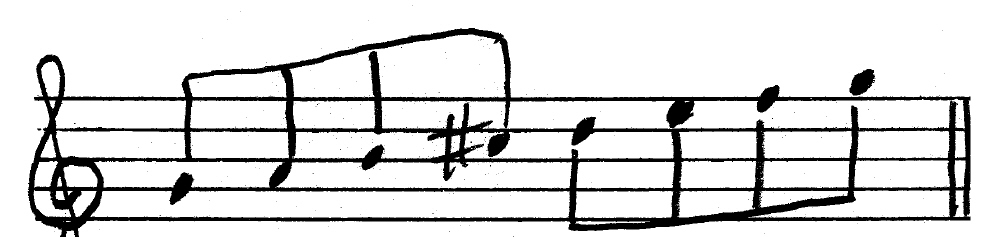

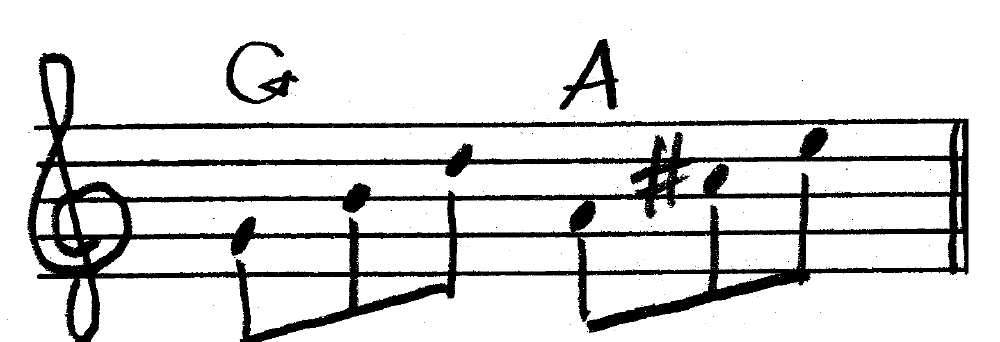

Here they are. The top chart is for C instruments and the bottom one is for Bb instruments. Click on the images to enlarge them. If possible, use the Aebersold accompaniment for “Round About” or have a pianist comp for you as you play the etude so you can hear how the lines work with the harmony.

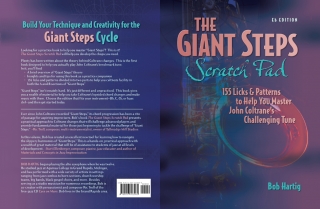

If you enjoy these exercises, look here for more, along with insightful articles, transcribed solos, and tips on jazz improv.

CORRECTION: Now that this article has been posted for a while, naturally I’ve noticed a transcription error in the C and Bb charts. (The original Eb chart is fine.) Since you can easily make the correction mentally, I’m going to simply tell you what it is. In measures 3-4 and 19-20, the chord symbol should not contain a sharp sign. The correct chord in both locations is as follows: for the C chart, A7+4; for the Bb chart, B7+4.