It is a weird feeling when a tornado strikes the neighborhood where you used to live, particularly when you weren’t expecting tornadoes at all that day. That’s how it was two-and-a-half weeks ago on Sunday, July 6. No one saw it coming–not anyone who lived in the stricken area, not the National Weather Service, not any Michigan-based storm chasers I know of, and certainly not me. All I thought was, “Dang, that’s some crazy lightning coming out of that cell to my northwest!” even as an after-dark tornado chugged its way from Byron Center across Cutlerville and Kentwood toward its last gasp near Breton Road south of 28th Street.

I’m writing about it only now because I’ve had my hands full with other things. It’s no longer news, but it certainly deserves some kind of writeup in this blog. After all, it was the most significant tornado to hit the Grand Rapids area in years, it caught the NWS by surprise, and it missed my old apartment by only a block. (Come to think of it, another tornado in 2006 also missed my present apartment by only a block, but I wasn’t around to see it. I was heading home from my previous day’s chase in Illinois. Lots of irony there, but I’ll leave it alone and stay on topic.)

The Storm

It was evening, and I was parked by the railroad tracks out near Elmdale, practicing my saxophone–which, if you know me, you understand is a regular habit of mine. The heat and humidity of the day had built to a slow boil beneath a capped atmosphere, but it appeared that the cap was breaking. Through the haze, I could see what looked like mushy towers off to my north. Right around sunset, I saw lightning streak through a cloud bank moving in from the west and thought, Nice. Bring it on. With mid-level winds forecast to be weak, I wasn’t expecting more than garden-variety storms, but given this year’s largely stormless storm season here in Michigan, any kind of flash and boom would be welcome.

With my practice session not feeling particularly inspired, I decided to call it and head home. The storm didn’t appear to be moving fast–not surprising, given the weak steering winds–but just north of my path . . . wow, that lightning was ramping up something fierce. I contemplated intercepting the cell, which clearly was quite active, but I had neither my laptop and radar with me nor my camera, nor, frankly, much desire. Sometimes it’s nice to just sit at home and let a storm rumble overhead.

By the time I arrived in Caledonia, the cell was flickering like a strobe light, and for half a minute, with more lightning advancing from the west, I thought I would sit in the church parking lot on the west end of town and let myself get eaten. Then I thought, Nah. Slow-moving storm with a lot of precipitable water–I just wasn’t into getting drenched during the mad dash from my car to my apartment. Besides, something in me really wanted to take a gander at the radar.

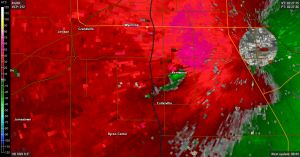

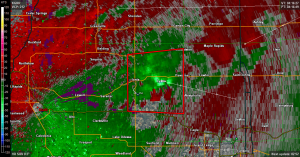

Once inside, I fired up GR3. Base reflectivity showed an amorphous clump of cells surrounded by lots of green: pretty much the disorganized, high-precipitation mess I expected. Then, out of pure force of habit, I switched to storm-relative velocity. Hmmm . . . what was that? Weak rotation just west of the airport radar seven miles north of me? That seemed odd. Curious, I back up a scan, which showed that the rotation had been stronger over Kentwood a few minutes earlier (see image.) Time for a look at the VAD wind profile. Well, now: mid-level winds were stronger than I had expected, around 40 knots, with southerly winds veering nearly 90 degrees through the lowest 4,000 feet. That would explain that. Going by reflectivity only, I’d never have suspected, but there it was, a definite mesocylonic signature. What did the previous scan show?

Yikes. Really? There over South Division Street, sitting on top of Cutlerville–that was one potent-looking couplet.* Kind of scary, really. Surface-based CAPE was something like 2,000, and forecast low-level helicity was more than adequate, over 200 m2/s2 in the lowest kilometer. Still, reflectivity looked like crap, the storm was wrapped in rain and not even severe-warned, and besides, this was Michigan. And that was two scans ago; the rotation had weakened considerably as it approached the airport. That would be the end of things.

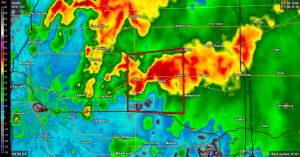

But it wasn’t. As the storms moved east, the low-level jet spiked considerably, and even the 500 mb wind got a brief burst of 50 kt. Over by Ionia, a cell began to organize, and this time there was no mistaking the telltale look of a supercell in the reflectivity product. KGRR issued a severe thunderstorm warning with mention of the possibility of a tornado.

A scan later, storm-relative velocity shows pronounced rotation. Base reflectivity (not shown) also showed a well-defined hook.

There were in fact four tornadoes according to the SPC’s final tally. The last three off to the east were brief EF0s, but the first one, which had initially caught my attention, did high-end EF1 damage in Cutlerville and injured six people.

Damage in My Old Neighborhood

After doing its worst damage on the west side of Division Street, the tornado moved northeast through my old neighborhood, Leisure Acres. The second photo at the top shows the view that greeted me as I turned off of Eastern Avenue onto Andover Street. Halfway down Andover, my old apartment was untouched, but just a block east (and no doubt to the south, though I didn’t look) was a trash heap: trees snapped and uprooted, big branches torn off, here and there part of a roof missing–all the signs of a weak tornado. But of course, weak is a relative word; a wind that can do that kind of damage is anything but weak, as those in its path would be quick to point out. Nevertheless, there’s a significant difference between a 100 mph wind that does mostly minor structural damage and a 180 mph wind that levels homes completely.

Half of the photos in this post were taken in the Leisure Acres neighborhood along my old street, Andover; the rest were taken on the west side of Division south of Fifty-Fourth Street. The damage on Andover was primarily tree damage, though that was obviously significant, and as you can see, homes didn’t escape unscathed. The worst appeared to have been the house shown to the right with part of its roof and side ripped out out by the wind.

I was told that much worse damage occurred to the west along Clay Avenue, and while I didn’t try to enter that area, a brief jaunt down Division Street revealed places where the damage was more intense. The most significant was what appeared to have been a large warehouse building that got completely destroyed–just a pile of blocks and steel beams, as you can see in the photos.

In the aftermath of severe weather events, communities tend to pull together and ordinary heroes emerge from outlying areas, bringing with them such skills as they possess and the desire to make life a little easier for those dealing with the destruction of their property. This man with the chainsaw was wandering along the street from house to house, inquiring whether anyone needed help sawing up downed trees. Giving what he had to offer. I asked his name and wrote it down, and now I’ve lost it. In the very slim chance that he should happen to read this article: Bravo, sir! Generously played.

“We Had No Warning”: The NWS’s Dilemma

Of course the NWS got hammered. “We had no warning,” storm victims said–and while most of the time that’s untrue, in this case they really had no warning. But before anyone makes the usual foolish comments about the NWS’s ineptitude and how they never get anything right–which is simply not the case–it would pay to understand a few things about tornadoes in Michigan.

Let’s start with this fact: The typical tornado-breeding systems of the kind that produce significant (EF2 and higher) tornadoes get forecast quite effectively here in West Michigan, as elsewhere in the country. Meteorologists are on top of such setups; they watch these systems develop days in advance and are most certainly monitoring each one closely as it arrives, with varying degrees of concern depending on its characteristics.

That leaves the atypical tornado-breeders: systems whose features wouldn’t automatically trigger alarm, whose storms may occasionally produce brief, weak tornadoes that spin up with little or no advance notice. Storms like these–often squall lines and sometimes, as in the case of July 6, unremarkable-looking rainy blobs–produce no persistent, telltale circulation in a storm’s mid-levels that a radar can detect twenty minutes before a tornado forms. Such storms are difficult to impossible to warn. In the case of a squall line, small circulations can hop around from scan to scan on the radar, now here and now there, and most of them never produce. The rare tornado that does occur can materialize between radar scans, which until very recently have taken four-and-a-half minutes to complete in severe weather mode. A lot can happen in that time, and on July 6, it did.

Without going into details that most of my readers are no doubt familiar with, the lads at KGRR deal with proportionately more of these atypical scenarios than forecasters west of the Mississippi. The difference between a Great Plains supercell and the kind of stuff we normally get in Michigan is substantial, and for forecasters here, that means fewer opportunities to look like heroes and plenty more situations in which they’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t. When they issue a warning and nothing happens–which is frequently the case with squall lines–the public accuses them of crying wolf; when they don’t issue a warning and a tornado pops up out of nowhere, the public thinks they’re idiots.

They are far from idiots. They are experts who deal with factors in the warning process that most people know nothing of. Their job is not an easy one, and anyone who believes he or she could do better is woefully ignorant of the complexities of severe weather and warnings. Think otherwise? Fine. Go ahead and spend a few weeks at the peak of severe storm season, trying to nail that volatile blob of Jell-O called the atmosphere to the wall. It’ll be an eye-opening experience as, equipped with state-of-the-art technology, you discover the difference between forecasting and fortune-telling.

Ironically, the Cutlerville tornado occurred shortly before KGRR was slated to implement the new SAILS update to their radar software. It’s amazing to see how drastically this software reduces scan times in severe mode–I now get level 3 downloads in as little as a minute and always substantially less than the nearly five minutes of pre-SAILS days. Had SAILS been operative on July 6, the tornado might well have been detected in enough time to issue a warning. Or not. Microscale conditions can change so rapidly that some tornadoes will still slip through the cracks. But the odds of detection have just improved significantly.

——————

* The image shows the meso over Kentwood. I have tried unsuccessfully to render the more vigorous Cutlerville scan on both level 2 and level 3 data from NCDC archives on GR2AE and GR3. After several hours of fiddling with the data files and consulting with chasers who are more technically gifted than I, I’ve concluded that I need to get some hands-on help figuring out how to use NCDC’s archived data. Sorry–I’ve done my best.