Amid my collection of storm chasing videos is an old VHS titled A Spotter’s Guide to Michigan Convective Weather. Produced in 2000 by Blake Naftel in collaboration with the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, the award-winning video is a vintage reflection of Blake’s dual passions for storm chasing and videography—a combination shared by countless chasers, but which in Blake’s case, having developed in a unique way at an opportune time, has forged a path that brings him today to the verge of a remarkable undertaking. But let me set the stage. . . .

Amid my collection of storm chasing videos is an old VHS titled A Spotter’s Guide to Michigan Convective Weather. Produced in 2000 by Blake Naftel in collaboration with the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, the award-winning video is a vintage reflection of Blake’s dual passions for storm chasing and videography—a combination shared by countless chasers, but which in Blake’s case, having developed in a unique way at an opportune time, has forged a path that brings him today to the verge of a remarkable undertaking. But let me set the stage. . . .

Long past are the days when storm chasing was the little-known, eclectic pursuit of a handful of pioneering weather photographers and researchers crisscrossing the Great Plains. Today, hundreds of chasers routinely pound the roads of Tornado Alley, and more are entering the fray all the time, influenced by what they’ve seen on TV but lacking any awareness of where it came from.

Yet storm chasing has roots—deep roots, a legacy of personalities, events, and endeavors that deserves to be cherished but is in danger of being lost. The time to preserve that rich heritage is now, when most of those who have created it are still with us. Now is the time to honor the colorful history of storm chasing and connect it to today’s talented generation of younger chasers and weather scientists and the future which is theirs to shape.

That is the vision that drives Blake Naftel to produce Storm Chasing: The Anthology. It is unquestionably the most ambitious cultural and historical project ever to focus on storm chasing. Given the grassroots character of chasing, it is fitting that an effort of such a landmark nature should arise not out of some big commercial production house, but from one of our own. Someone who has storm chasing in his blood and cares about it deeply enough to portray it with honesty; better yet, to let those who have contributed to it do the portraying on their own terms.

There will be no scripting, no manufactured storyline. There will just be stories, told by those who have lived them, beginning with the very origins of storm chasing. There will be storms, of course—unadorned, historical storms as well as contemporary ones; storms you may have chased yourself as well as ones from decades past that you’ve only heard of and wished you could have experienced. There will be insights into the rise and development of tornado research. And there will be much more.

That is, provided Blake can pull off a venture of such magnitude. Those of us who know him think he can. He’s immensely talented as both a chaser and a cameraman with years of experience in TV journalism, he has a penchant for the truth, and he’s motivated by sheer love for his subject. The project is huge in scope and fraught with challenges. But Blake is embracing those challenges, and the result promises to be unlike anything else that has ever been attempted.

And with that, I’ll let Blake tell the rest of the story.

—————

Question: Let’s start with a bit of personal history, the stuff that has forged your path toward this project. What first got you started both as a storm chaser and as a professional cameraman?

Blake: My interest in severe weather, meteorology, and storm chasing developed early, just before I turned five. I recall being exposed to The Wizard of Oz—specifically the tornado sequence—and more importantly, to the NOVA-WGBH documentary “Tornado,” which was first broadcast in November 1985. I was determined to record the program, but my family lacked a VHS VCR at that time. Fortunately, my uncle in Detroit had one, and just after Thanksgiving 1985, I had a copy of the broadcast. The following year, my parents purchased a VCR, and the tape was played extensively—to the point of memorization. The tape found its way to friends’ homes, where instead of children’s cartoons, the sixty-minute program on tornadoes, storm chasing, and the Barneveld, Wisconsin, tragedy was required viewing.

Blake: My interest in severe weather, meteorology, and storm chasing developed early, just before I turned five. I recall being exposed to The Wizard of Oz—specifically the tornado sequence—and more importantly, to the NOVA-WGBH documentary “Tornado,” which was first broadcast in November 1985. I was determined to record the program, but my family lacked a VHS VCR at that time. Fortunately, my uncle in Detroit had one, and just after Thanksgiving 1985, I had a copy of the broadcast. The following year, my parents purchased a VCR, and the tape was played extensively—to the point of memorization. The tape found its way to friends’ homes, where instead of children’s cartoons, the sixty-minute program on tornadoes, storm chasing, and the Barneveld, Wisconsin, tragedy was required viewing.

Picking up on my interest in severe weather, my mom began telling me stories of the tornado she witnessed only a few years prior in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on May 13, 1980. Descriptions of the “twin tails” rotating around one another from her viewpoint at the Civic building in downtown Kalamazoo captivated me. The iconic Kalamazoo Gazette front-page newspaper photograph furthered my fascination, and soon I was checking out every book on tornadoes that I could locate at the Kalamazoo Public Library.

Later in the spring of 1986, my mom visited my godmother in Kansas City, Missouri, where, at the time, the National Severe Storms Forecast Center was located. She returned with numerous informative brochures and spotter’s guide material, which I instantly became hooked on. Additionally that year, Mom designed a flip book with illustrations of the progression of the events from May 13, 1980—sunshine, clouds, greenish-grey skies, lightning, the tornado’s approach, its wrath—concluding with calm, blue, sunny skies. It depicted the day just as it had transpired. I still have this little book, entitled Tornado! (“For Blake, from Mom.”)

Zooming ahead about a decade, I began developing a great interest in cameras—specifically in motion picture cinematography, videography, and 35 mm photography. This was early in the Internet age, and multiple interests of mine were spanning territories that included affordable access to used camera equipment, fee-based and free weather data, and newsgroup networking with seasoned storm chasers and meteorologists across the United States and Canada (WX-TALK, WX-CHASE).

Upon receiving my driver’s license, I began to actually chase storms in 1996‒97. My chasing at the time was all local, learn-as-you-go, with my knowledge of storm structure and my chase style informed by various storm chase highlight videos which I swapped with Bill Reid, Jim Leonard, Tim Marshall, Warren Faidley, Scott Woelm, Bruce D. Lee, Roger Edwards, and Rich Thompson, among others.

At this point, I also began experimenting with HTML design, early online video, and the development of a regional group of storm spotters and chasers who would gather video of severe weather events in Michigan for the purpose of SKYWARN spotter training. Eventually, after making contact with the National Weather Service in Grand Rapids, I created a statewide training video for storm spotters, developed though my early attempt at social networking and video sourcing. The now long-defunct website known as MSIT (Michigan Storm Intercept Team) was one of several web pages I created back then.

During the same period, I began an online business buying and selling used motion picture and video camera gear. By doing so, I acquired several different types of cameras, learned about them by trial and error, and frequently focused their lenses on the weather, nature, and people around me. This approach mixed in with a “vintage” look I was going for at the time, and it eventually became a style I utilize to this day.

Then in 1998, the event occurred that would lead me to a future career in photojournalism and TV. On June 11, I was storm chasing across north-central Indiana in Elkhart and Kosciusko counties. It was a very basic chase with paper maps, weather radio, black-and-white television tuned to local media for radar updates, and a general target area based on the parameters. It did not seem like a prime tornado day, although when I recall the dynamics of the system today, it now is very obvious. Long story short: I ended up successfully intercepting and documenting several brief tornadoes which struck south and northeast of Nappanee, Indiana, on SR 19. The chase had at least one nerve-wracking moment when my vehicle’s transmission temporarily gave out in the path of the oncoming tornado, which was less than a mile-and-a-half away. Fortunately the transmission kicked back into gear, allowing me a northern escape.

Once in a safe position, with SVHS camcorder tripoded, I filmed the wall cloud and its attendant weak tornadoes as they continued dipping down to the northeast. The following morning, I saw the amateur video of another tornado near Bristol, Indiana—which occurred prior to what I witnessed—showcased on the morning news on WSBT 22 and WNDU 16. Prompted by my growing interest in broadcast meteorology, TV news, and videography, I called WNDU and spoke to Mike Hoffman, the chief meteorologist, about my own video. He took great interest and asked if they could buy the video for their 11 p.m. newscast on June 12.

After another round of severe weather across the same region that day, I ended up meeting the station’s chief photographer in White Pigeon, Michigan. I gave him my original tape, and later that evening, my video of the Nappanee tornadic event appeared on WNDU’s newscast.

From that point, I began freelancing for local media and soon became involved with the production side of local television. This eventually grew into my various incarnations as a photojournalist, reporter, weather producer, and technician in the years that followed.

Q: What were those early years like for you? With whom did you chase? How have your experiences and personal interests influenced your videographic approach, which goes beyond chronicling the storms to also documenting the human and historical sides of storm chasing?

B: My early years of storm chasing were very local, restricted to traveling through the western portions of lower Michigan, with occasional trips to northern and central Indiana. Typically, those early trips were either with high school friends or solo, utilizing my 1989 Ford Taurus wagon or a dilapidated 1978 Chevy van my friend Aaron Graham would occasionally drive. Fuel cost was still low, just 79 cents in 1997, so traveling at length to witness severe thunderstorms was not of great significance. Even back then, I was using multiple documentation formats, frequently hauling motion picture film, video, and still photography equipment together into the field just to chronicle everyday Michigan severe thunderstorms. For the more vivid events, I preferred to shoot silent Super 8 color movie film, whereas VHS/SVHS video was a near-constant format that seemed to be always rolling.

I was intrigued by tornadoes on film—namely, the early NOAA-produced films—versus video. The quality, grain, and occasional scratches and dust flecks produced by the projector created a look I was determined to capture. And I did, experimenting with different cameras, formats, and photographic styles. I didn’t confine myself to severe weather or storm chasing only; family events, pets, and the natural surroundings across my hometown area in Texas Township, Michigan, also provided a dynamic environment full of interesting subjects and colors. My subject range continued to expand as I became involved with broadcast photojournalism and developing my own shooting style. Again, it was all by trial and error.

My first chasing exposure to the Plains states was in 1999 and more expansively in 2000. Prior to this point, I had only lived vicariously through the videos of other chasers with whom I had networked through the Internet. Bill Reid, from the Los Angeles region, was one individual who had direct influence not only on my chase documentation style but also on my musical tastes at the time. Over the years, we swapped storm chase highlight videotapes and conversed online, and this eventually led to a distant friendship, which in turn opened the doors to my working for Tempest Tours, with Bill serving as tour director.

In 2001 I was invited to drive and help forecast for Storm Chasing Adventure Tours, run by Todd Thorn. By then I was twenty years old and attending college, and the appeal of having all my lodging and fuel costs paid for seemed too good to pass up. That experience involved a huge tour: three vans full of individuals from across the world as well as three media vehicles from The Weather Network, the Denver Post, and WKOW-TV in Madison, Wisconsin. It was an eye-opener for someone who had primarily chased solo or within small groups, and only locally, never throughout the Plains states. I don’t regret the experience whatsoever, but I chose not to drive for a second tour scheduled directly after the first. Tours can be exhausting, especially those with so many participants!

That year was also the first operational year of Tempest Tours, a company formed by documentary filmmaker Martin Lisius, who was good friends with Bill Reid. I had been in contact with Martin in previous years, ordering his Chasing the Wind, Chasers of Tornado Alley, and StormWatch productions. Out of the blue, Bill contacted me, inquiring about my interest in being a paid driver/guide for Tempest Tours the following year. I was both humbled and floored! I accepted the offer, and in May 2002, I began a five-year stint with Tempest. During that time, I developed many new friendships that would never have been possible without the flexibility that working for a storm chase tour company provided.

Concurrently, I was also working on my geography/GIS degree at Western Michigan University, and I found myself drawn intensely to the mecca of academic severe weather research and meteorology in Norman. The tours, based out of Oklahoma City, provided a wonderful gateway to interacting with other meteorologists and storm chasers who shared similar interests.

Due to the requirements of the broadcast news industry I was now working in, 2008 was my last year working in the storm chase tour circuit. The peak chase month of May is a “sweeps” period in newscasting, and vacation is rarely allowed. So the tours had to take a back seat. But the entire experience was fantastic, one that created friendships which continue to this day and left me with amazing images of visual water vapor, along with an enjoyment, courtesy of Bill Reid, of the musical artists Stan Ridgway and Klaus Nomi. It had been a remarkable, full, and deeply formative passage in my life—and I had it all documented extensively on videotape.

Q: On to your project. Describe Storm Chasing: The Anthology. What is it? How did you think of it? How is it different from other storm chasing videos and documentaries such as Discovery Channel’s Storm Chasers series, and what do you hope it will accomplish? Why is it important—and why now?

B: Storm Chasing: The Anthology developed out of an earlier, untitled project from the 2003‒2004 era which I had shelved. The first concept was a 60-minute documentary on the human element of storm chasing. At that point, I had accumulated hundreds of hours of my own storm chasing endeavors—as well as the people I had been chasing with at the time. Impromptu interviews from the field were gathered, but it was all very “reality TV” to me, and that was a style I was losing interest in.

Jump ahead ten years. Much had changed in the world of storm chasing. Several reality TV shows had transpired, including Storm Chasers, Tornado Road, and smaller spin-offs. I still had all of my original material sitting around in boxes, but had lost interest in doing the earlier concept. Then came the tragedy of May 31, 2013, in El Reno, Oklahoma, which affected the entire storm chasing community and touched me in a very personal way. That event served as the initial trigger for me to revisit my old project and envision a different and expanded approach to it, and it has given me the drive to complete it.

The idea is to present a complete (or as complete as possible) visual history of storm chasing culture. This grows out of the humanity aspect of the original concept, but instead of using a narrator, it will be told through the words, stories, and images of every storm chaser and meteorologist who participates, revealing the full, fascinating decade-by-decade evolution of storm chasing.

To date, the many documentaries and programs about storm chasing have focused on specific events, people, or scientific endeavors, with the 1978 documentary In Search of Tornadoes being the first widely broadcast feature on the subject. In contrast, Storm Chasing: The Anthology is comprehensive. It will serve as a sweeping visual history lesson and an archive of storm chasing culture. Through this project, I plan to preserve the legacy of past generations of the activity, connect that heritage to what chasing is today, and make the results available as an educational resource for present and aspiring meteorologists and severe weather enthusiasts.

In time, I hope to have this project serve as a visual thesis towards the development of a digital, cloud-based, multimedia archive of severe weather. This would be university-based and available as a research and reference resource. That is far down the line, but it was another trigger to doing this project. As individual meteorologists and storm chasers pass on, their collections of imagery and work run the risk of vanishing; the archive would answer that concern. Obviously, you cannot preserve everything, nor is that my intention. One can, however, preserve vast amounts of a subject, and I feel that now is the time to make a push toward that end.

Q: Who is Storm Chasing: The Anthology for? Primarily storm chasers? Or do you hope to reach a broader audience? How will this anthology benefit viewers?

B: This production is being created for anyone with an interest in history, severe weather research, meteorology, and the activity of storm chasing. Granted, the core audience is those who are, or have been, directly involved in storm chasing. The benefit to viewers will be a broad education on all aspects of storm chasing as an activity.

Initially, a condensed premiere version will be released, followed by a six-part anthology. The latter obviously may take far more work than I had initially thought, and at the moment, this is a completely independent effort—so I ask everyone to please bear with me. In terms of a broader audience, upon completion, I wish to make the anthology available to libraries and academic institutions. In time, I would love to present this program on a broadcast/web streaming platform—specifically, PBS. The film festival circuit will also be a part of the exposure to other individuals who would not normally have a direct interest in this subject. As for making the anthology available for individual purchase, that’s in the plans, but I’ll first need to take care of the necessary copyright and licensing requirements.

Q: This is obviously a huge undertaking, spanning roughly sixty years of storm chasing history. Given your talents, experience, and relationships with storm chasers from veterans to talented younger chasers, you seem uniquely qualified to make it happen. What have you already done, what do you still need to do, and how long do you think it will take?

B: So much has been accomplished already! A tremendous amount of video, film, and other material has been gathered over the past decade. But much remains to be done. The core of the project involves my completing fifty-plus interviews of individual storm chasers and meteorologists across thirty-one states and Ontario, Canada. The Kickstarter campaign is intended to defray my travel expenses. With that campaign now in its final week, concluding on July 25, I am still seeking additional funds to offset the combined 7 to 10 percent fee that Amazon and Kickstarter will take from the funding pool.

My next task is acquiring a vehicle for travel. I share a vehicle presently and will likely be renting one for the trip. I’m currently approaching local car dealerships and national rental vehicle agencies about sponsoring a car. One of these options will be secured in the next month.

I am also still deciding what format to shoot the interviews on. Presently I have the offer of older, loaned (fee-free) gear from friends, and that will likely be the route I take.

Once the interviews are complete, editing will be the monumental task on my mind, along with production design. I am confident that a condensed premiere version would be ready by the summer of 2015. And I earnestly hope to have the six-part anthology completed by October or November 2015 and available either as BluRay/DVD or as a digital download. There is the whole aspect of meeting the deadlines promised to backers of this project—so 2015 will be a very busy year for post-production!

I’m always eager for assistance and will likely be inquiring with local or regional production firms and/or academic institutions in order to complete the project in a timely manner.

Another big reality is securing an income—or multiple-income sources—locally or regionally while working on the post production phase of this project. Working independently, I’m taking a great risk, and I find that both exciting and unnerving. I’m leaving my full-time job at WWMT on August 22 to set out for the month or so it will take me to complete the interviews, and I have nothing official lined up upon my return. While I have requested an unpaid extended leave from the station, it is only a possible consideration. Moreover, the focus required for the editing phase of this project is immense, so if I could secure local part-time or freelance employment within the Grand Rapids area, that would work quite well. Although I cannot say what the future holds, doors continue to open in new directions for me each step of the way with this project, and I have faith that everything will work out.

Upon my return, hours upon hours of video will be ingested and logged. Not only so, but countless hours of B-roll video material dating back to David Hoadley’s earliest storm chasing movies will also need to be digitally archived. All the multimedia material I’ll be dealing with comprises well over 1,000 hours! Frankly, thinking about how to bring all of that together boggles my mind at the moment. This is all a real-time process, and that is one reason why I am choosing to release this as a six-part anthology.

I may need to seek out a production team to assist in the design and distribution of this project somewhere down the line. So let me reemphasize that while Storm Chasing: The Anthology is currently an independent effort, I am open to assistance from the outside, including collaboration with other filmmakers and producers.

Q: Who are some of your supporters? Do you have a projected release date?

B: The supporters of this project are far too numerous to list here. I am extremely thankful to everyone who has pitched in to help make this project move from a vision to a reality. The projected release of the premiere version is in the early fall of 2015. I hope to feature it in the Oklahoma City/Norman, Oklahoma region, potentially coordinating with the AMS or NWA conferences between September and October. No premiere location is official yet; that too remains on my vast to-do list.

As for the six-part anthology disc/digital download version, as I mentioned earlier, I plan to make it available by November 2015, barring any snags along the way.

Q: What are your needs? How can people help?

B: Full project details and proposed budget can be located via: https://stormchasinghistory.net. The ongoing Kickstarter campaign runs until July 25 at 11:10 a.m. ET.* While the $7,000 funding goal was met in twelve days, additional backing will only make this project better! Please continue spreading the word about this project through social media. And if you love a mix of history, storm chasing, and storytelling, then consider adding your financial support to create this anthology series. Any amount, large or small, makes a difference and is greatly appreciated.

Q: Anything else you’d like to say, Blake?

B: Thank you to everyone who has supported the development of Storm Chasing: The Anthology! This production would not be a reality without the collaboration, belief, and interest of others! I am eagerly looking forward to getting on the road with this project, and I will be providing field updates of my travels, once they commence, via Facebook, Twitter, and the stormchasinghistory.net homepage.

——————————-

* Blake’s Kickstarter campaign concluded at the time stated and was highly successful. He raised $10,200, well beyond his goal. Considering that the project will involve far more than travel expenses, those who contributed can consider their generosity well-placed.

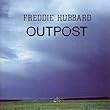

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.