You read right: The Giant Steps Scratch Pad has finally hit the streets!

I hadn’t wanted to give further updates until now because it seemed that I kept running into snags and delays. That kind of news gets embarrassing to write about after a while, and no doubt it’s tiresome to read. But all the hurdles have finally been crossed, and I am extremely pleased to announce that my book of 155 licks and patterns on Giant Steps changes is at long-last published and available for purchase.

Let me quickly follow with this caveat: The Eb edition is the one that is presently available. However, with that trail finally blazed, Bb, C, and bass clef editions are all in the works and will be following shortly. I finished editing the Bb edition earlier today, and I hope to complete the job tomorrow, so look for it in a day or two, or at least sometime this week. After that will come the C and bass clef editions. (UPDATE: ALL FOUR EDITIONS OF THE GIANT STEPS SCRATCH PAD ARE NOW AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE. SEE BOTTOM OF PAGE TO ORDER. CLICK AND ENLARGE IMAGE TO YOUR LEFT TO VIEW A PAGE SAMPLE FROM THE Bb EDITION)

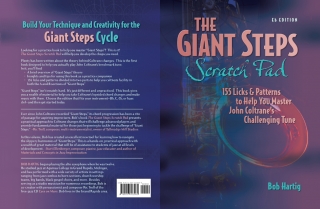

If you’ve ever wanted to build the technique to blaze your way through the changes to John Coltrane’s jazz landmark, “Giant Steps,” this is the book to help you do it. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind. Here’s the cover copy for it:

Build Your Technique and Creativity for the Giant Steps Cycle

Looking for a practice book to help you master “Giant Steps”? The Giant Steps Scratch Pad will help you develop the chops you need.

Plenty has been written about the theory behind Coltrane changes. This is the first book designed to help you actually improvise on John Coltrane’s benchmark tune. In it, you’ll find

- * A brief overview of “Giant Steps” theory

- * Insights and tips for using this book as a practice companion

- * 155 licks and patterns divided into two parts to help you cultivate facility in both the A and B sections of “Giant Steps”

“Giant Steps” isn’t innately hard. It’s just different and unpracticed. This book gives you a wealth of material to help you take Coltrane’s lopsided chord changes and make music with them. Choose the edition that fits your instrument—Bb, C, Eb, or bass clef—and then get started today.

“Ever since John Coltrane recorded ‘Giant Steps,’ its chord progression has been a rite of passage for aspiring improvisers. Bob’s book The Giant Steps Scratch Pad presents a practical approach to Coltrane changes that will challenge advanced players and provide fundamental material for those just beginning to tackle the challenge of Giant Steps.’” —Ric Troll, composer, multi-instrumentalist, owner of Tallmadge Mill Studios

“In this volume, Bob has created an excellent new tool for learning how to navigate the harmonies of ‘Giant Steps.’ This is a hands-on, practical approach with a wealth of great material that will be of assistance to students of jazz at all levels of development.” —Kurt Ellenberger, composer, pianist, jazz educator and author of Materials and Concepts in Jazz Improvisation

I’ll of course be putting up an advertisement for the book on this site. But no need to wait for that. If you’re an alto sax or baritone sax player, you can purchase the Eb edition right now!

Trumpeters, tenor saxophonists, soprano saxophonists, and clarinet players (did I miss anyone?), the party is coming your way next, so keep your eyes open for the next announcement.

It seems strange to me that something like this book hasn’t been done before, but as far as I know, The Giant Steps Scratch Pad truly is unique. It has been a lot more work than I ever anticipated, but I’m really proud of the results. Major thanks to my friend Brian Fowler of DesignTeam for creating such a totally killer cover for the print edition. But there’s more to this book than good looks alone. I trust that those of you who purchase it will find that its contents live up to its appearance. If you’re ready to tackle Coltrane changes, this book will give you plenty to keep you occupied for a long time to come.

NOW AVAILABLE IN C, Bb, Eb, AND BASS CLEF EDITIONS, AND BOTH IN PRINT AND AS A PDF DOWNLOAD.

Instant PDF download, $9.50

C edition

Bb edition

Eb edition

Bass clef edition

Print editions–retail quality with full-color cover, $10.95 plus shipping: order here.