The summary follow-up to my previous post is, I busted with L. B. LaForce during last Wednesday’s high-risk day in Illinois. Tornadoes occurred that day, but overall the scenario was a disappointing one for us. If anything, it was a lesson to trust my initial gut instinct, which told me to stick close to Indiana, where a moisture plume and 500 mb jet were moving in. Nice, discrete supercells eventually fired up south of Indianapolis while L. B. and I putzed around fruitlessly with the crapvection northeast of Saint Louis. And that’s all I’ll say about that–not that I couldn’t say more, but I want to talk about yesterday’s far more potent event in southern Michigan.

You don’t need a tornado in order to make a neighborhood look like one went through it. That axiom was amply demonstrated yesterday in Calhoun County, where straight-line winds wrought havoc the likes of which I don’t recall having ever seen here in Michigan. We’ve had a couple doozey derechoes over the past few decades, but I don’t think they created such intense damage on as widespread a scale as what I witnessed yesterday. Northeast of Helmer Brook Road and Columbia Avenue in Battle Creek, across from the airport, the neighborhood looked like it had been fed through a massive shredder. We’re talking hundreds of large trees uprooted or simply snapped, roofs ripped off of buildings, walls caved in, road signs blown down, trees festooned with pink insulation and pieces of sheet metal, yards littered with debris, power lines down everywhere…it was just unbelievable. Not in the EF-3 or EF -4 league, maybe, but nothing to make light of.

Yesterday was the first decent setup to visit Michigan so far this year. Of course I went chasing, not expecting to see tornadoes–although that possibility did exist–but hoping to catch whatever kind of action evolved out of the storms as they forged eastward. It being my first time doing live-streaming video and phone-ins for WOOD TV 8 made things all the more interesting. As it turns out, I was in the right place at the right time.

When I first intercepted the storms by the Martin exit on US 131, I wasn’t sure they would amount to much. Huh, no worries there. As I drove east and south to reposition myself after my initial encounter, the storms intensified and a tornado warning went up for Kalamazoo County just to my south.

Dropping down into Richland, I got slammed with heavy, driving rain. The leading edge of the storm had caught up with me. I wanted to get ahead of it and then proceed south toward the direction of the rotation that had been reported in Kalamazoo. Fortunately, M-89 was right at hand, and I belted east on it toward Battle Creek.

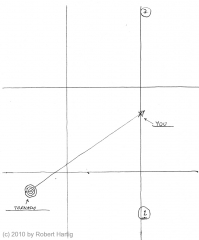

On the west side of Battle Creek, I turned south on M-37, known locally as Helmer Brook Road. GR3 radar indicated that I was just grazing the northern edge of a couplet of intense winds. It didn’t look to me like rotation; more likely divergence, a downburst. As I continued south down Helmer Brook toward the airport, the west winds intensified suddenly and dramatically, lashing a Niagara of rain and mist in front of me and rendering visibility near-zero. I wasn’t frightened, but I probably should have been. Glancing at my laptop, I noticed that a TVS and meso marker had popped up on the radar–smack on top of my GPS marker.

Great, just great. So that couplet I thought was a downburst had rotation in it of some kind. Well, there was nothing I could do but proceed slowly and cautiously and hope that the wind didn’t suddenly shift. It didn’t, and as I drew closer to the airport, it started to ease up, visibility improved and the storm moved off to the east.

That was when I began to see damage. In the cemetery across from the airport, trees were down. Big trees, and lots of them. Blown down. Snapped off. I grabbed my camcorder and started videotaping. But the full effects of the wind didn’t become apparent until I turned east onto Columbia Avenue near the Meijer store.

My first thought was that a tornado had indeed gone through the area. But with most of the trees pointing consistently in a northeasterly direction, the most logical culprit was powerful straight-line winds. Parking near a newly roofless oil change business, I proceeded to shoot video and snap photos. I’ll let the following images tell the rest of the story.