If you want to develop fluency at voice-leading and switching keys, cycle exercises are mandatory and the cycle of fifths is supreme. Taking dominant patterns and licks around the cycle of fifths is a longstanding habit of mine. As with a lot of musical disciplines, at first I delayed, I kicked, I resisted tackling this one for a long time because, well, it was work. Finally I decided to buck up and eat my spinach, and today the circle of fifths is a key component of my practice regimen, particularly for V7 chords.

After all, the dominant seventh, more than any other chord, defines the key center; it’s the chord that screams “resolve me!” So it pays for sax players and other jazz improvisers to consistently drill their ears and their fingers with exercises that can build their facility with dominant seventh chords.

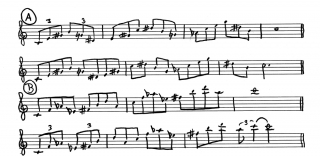

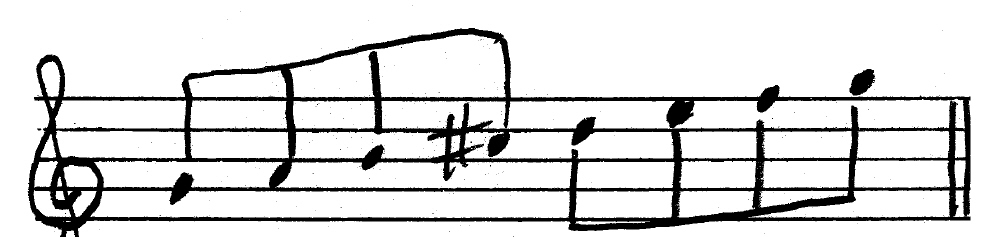

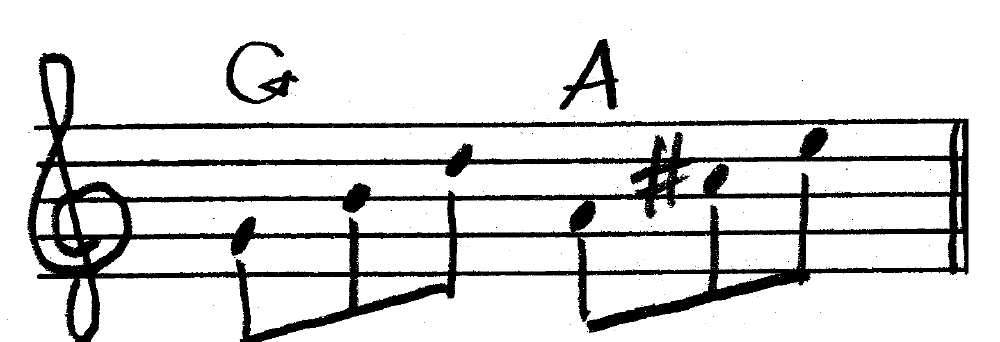

Here’s one such exercise that I’ve been having fun with lately. Click on it to enlarge it. There’s nothing mysterious about this little motif; I could pull it off easily in a number of keys right where I stand without making a practice issue of it. I’ve practiced enough related material that my fingers already know the way. But spotlighting the figure makes it likelier that I’ll use it in my solos; it ensures that my technique will follow me into any key; and, as with all cycle of fifth exercises, it helps me hear how the pattern lays out in root movements by fifth.

For each dominant chord, the exercise ascends chromatically from the ninth to the third, and then from the root to the seventh. I’ve set it in triplets, but you’ll want to experiment with different rhythms. I might add, this little motif sounds great in blues solos.

No need for me to say more–except, of course, to pester you to check out more exercises on my jazz page. Have fun practicing!