With this year’s severe weather season ramping up–as I write, Missouri and Arkansas are primed for supercells and tornadoes later today–I want to share the following with my fellow storm chasers. Many of you are people I know and care about, and some of you are quite close to me. I know some of the risks you take because I take them myself; we all do, to varying degrees. To my thinking, tornadoes are usually at the lower end of the risk spectrum. At the top is what happens on the road. That’s something over which we have considerable control, and with it, a responsibility for our own safety and the safety of others.

In a heartbeat, an exciting chase can turn into a second or two of horrified disbelief followed instantly by noise, violence, injury, and perhaps death. I know because I’ve lived it, and I hope no one else I know ever has to. That’s why I’m sharing the following account, written last December. Perhaps it’ll inspire you to exercise greater care and awareness on the road. Please take it to heart. I’d like it to be a long time before the next set of initials gets outlined on the radar by Spotter Network icons—and when that day does arrive, I don’t want those initials to be yours.

——————————-

Saturday, December 7, 2013.

A short while ago, I was lying on my side on the living room couch, giving Lisa’s cat a full-body rubdown and listening to her purr. Siam is one of the sweetest, best-behaved little creatures you could hope for, affectionate and enormously tactile. Being held and petted are things she takes for granted as her natural due, and she gets plenty of such treatment. So there was nothing remarkable that I should be stroking her soft, cream-and-chocolate fur.

And yet, there was everything remarkable about it. When you’ve nearly had your life suddenly snuffed out just before the holidays, the most commonplace act can strike you as extraordinary.

The fact that I am still here to pet this vibrant, blissfully thrumming little motor . . . that I am here to see Lisa smile, and to hear her laugh, and to look into her sparkling eyes as I hold her in my arms . . . that I am here to tell my dear eighty-eight-year-old mother and my sister, Diane, that I love them, and to share more beers with my friends, and to turn the ignition switch in my “new” used Toyota Camry which, as of yesterday evening, has replaced the one I lost three weeks ago . . . these things are remarkable. Never fool yourself into thinking that the simple and the everyday are anything less than a gift and a miracle.

Things could have turned out very differently. By now, my body could have been lowered into the cold earth, leaving my loved ones to face this Christmas with broken hearts instead of warmth and gladness. Instead, I am still here and blessed with, surrounded by, reminders that the simple act of petting the cat, or lifting this mug of hot chocolate that Lisa whipped up for me a little while ago, or watching downy snowflakes dance in the air beyond my balcony slider, or even feeling the diminishing but still-present pain of a cracked sternum, is an extraordinary thing.

The Setup

On November 17, I was chasing storms in eastern Illinois and western Indiana with my friends Tom Oosterbaan, Rob Forry, and Shawn Kellogg. The occasion was an unusual late-season setup featuring a vigorous, negatively tilted trough digging into the Midwest. On its eastern side, a surface low was pulling in moisture-laden southerly winds from the Gulf of Mexico as it tracked northeast through the Great Lakes.

For a good week, I had been following the forecast models with both skepticism and growing excitement as they progressed from the meager CAPE one expects this time of year to unseasonably high instability, mid-60s dewpoints, and some truly rabid wind shear. On November 16, the Storm Prediction Center issued a moderate risk for its day 2 convective outlook, then upgraded it to a high risk on the morning of the 17th. The ingredients were falling into place for the kind of high-shear/low-CAPE tornado outbreak that is typical of the Great Lakes. It would culminate in the deadliest, most violent November outbreak on record.

The setup bore some disturbing similarities to the notorious April 11, 1965, Palm Sunday Outbreak. And it wasn’t happening in Oklahoma or Texas. For a change, it was all coming together in my backyard, so to speak. Chasers from all over the map had converged on Illinois and Indiana–hardly the heart of Tornado Alley, but the most chaseable terrain in the world when it does produce.

Although Rob was willing to drive his Jeep, I volunteered my 2002 Camry. I had acquired it last February, and it was in great shape and was a comfortable ride. At last I had a roadworthy vehicle, and having benefited so often from other chasers driving their vehicles, I was pleased to be able to provide the transportation for a change.

We left Grand Rapids around 8:00 a.m. and met briefly for breakfast with Bill Oosterbaan and Kim Howell down at Kim’s house in Niles. Kim had prepared a generous spread for us (Kim, you’re the swellest!), but we were in a rush and had to just wolf it down, then Rain-X our windshields and hit the road. We did, however, make time to do one last thing before we took off. Joining hands, all six of us prayed, asking the Lord’s protection for us and for those in the areas that would be impacted by the storms. I believe that prayer was providential. None of us in my vehicle had an inkling of what lay in store for us a few hours later.

The Chase

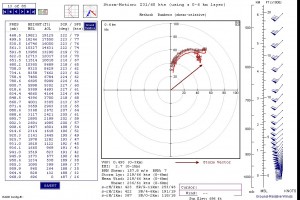

Our target was northwest Indiana around Rensselaer, where the 500 mb jet max looked to nose in over substantial low-level instability. With storm motions forecast at 60 knots (see NAMM hodograph–click to enlarge), the storms would be rocketships, and it seemed that our best bet would be to set up east of them, watch the radar, and then jockey into position and hope for the best.

I wish we had stuck with that plan. But the big, discrete supercell which proved to be the day’s main player showed strong, persistent circulation, dropping a string of strong to violent tornadoes–including the deadly Washington, Illinois, EF-4– on its journey northeast from Peoria toward Chicago. Bill and Kim decided to go for that one and wound up intercepting a rain-wrapped tornado.

On our part, the storm looked mighty tempting, but we chose to let it go, not wanting to chase it in urban territory. That left us with the other storms which were approaching from the southwest, and we made the mistake of heading out to meet them rather than letting them come to us. It was a defensible decision: the storms were beginning to congeal into a line, and we wanted to catch them while they were still reasonably discrete. As it turned out, we’d have done fine had we simply exercised patience. But instead, we headed west into Illinois, then dropped south and ultimately wound up backpedaling east back across the border to intercept an HP supercell that was showing rotation on the radar.

Rob was driving and I was sitting in the front passenger seat with my laptop on my lap, monitoring the radar and navigating. I’ve mentioned that Illinois and Indiana easily comprise some of the best chase territory anywhere. Their flat, wide-open stretches of agricultural land let you see for miles, and their regular grids of paved country roads make for easy driving. Even the wet gravel roads are generally far easier going than the slippery gumbo out west. You just can’t ask for a better road network or better topography.

Southwest of the town of Oxford, Indiana, our storm appeared to crap out on us on the radar. The echo weakened, and while the storm just to the southwest was tornado-warned, the base reflectivity suggested a comma-head on a small bow echo, not a supercell. That was the last radar scan we got before we lost Internet connection. And storms can reorganize rapidly, and–well, ours did. Shortly after, an inflow jet shot across the road in front of us from the south and then rapidly enveloped us. What the . . . ? Rob rolled down the window, and we could hear a roar to the north. What was causing it? An updraft region had to be over there. But it was wrapped in precipitation, and telltale storm features were utterly lacking. Yet logic told me that somewhere within that bland-looking sky, a mesocyclone was buried, possibly even a tornado. At the very least, some kind of high-wind event had to be taking place nearby.

Not only so, but a dark shadow was moving along to our south, heading tangentially in front of us. Tornado? Just a darker cloud in that unremarkable sky? Impossible to tell. I shot some video, hoping that the camera would reveal features that my naked eye couldn’t discern, but there was no such luck. All it gave me was my sole record of our chase that day.

A look at the reflectivity on Rob’s cell phone app a couple minutes later revealed that our storm, which had appeared weak and disorganized in the previous scan, had in fact morphed into an embedded supercell. We had been on the southern end of the hook.

As we headed into Oxford, we began to see signs of significant wind damage–nothing tornadic, just straight-line, but still a handful for the residents of that town to have to clean up.

We were losing our storm, and once we were on the other side of Oxford, Rob picked up the pace. By then, though, I think our chase was effectively over. The storms were beyond us and moving too fast for us to catch up.

The Crash

Not quite two miles east of Oxford, the road we were on, eastbound SR 352, intersects northbound US 52. We were traveling at a good clip–too fast for conditions, as I know Rob will agree.

Ahead of us lay a hillock where a railroad track crossed the road. It was a blind rise that blocked our view of the other side. Rob slowed down for the tracks, but we were still probably doing 40 mph when we crested them and got our first glimpse of what lay beyond. To our horror, a stop sign and a divided highway were situated downslope no more than 200 feet away and probably closer. And to make matters worse, a vehicle was pulling out of a service road on the right into our lane. Rob swerved and braked instantly, but the pavement was wet, we were heading downhill, my nearly new all-weather tires failed to grab, and we skidded into and across the southbound lane on a collision course with a northbound van.

I remember watching the grill of the other vehicle looming toward me. The next instant, there was a bang, and our vehicle careened across the rest of the lane and came to a stop on the far side of the highway. I don’t remember the airbags deploying, but they did, and no doubt they saved Rob and me from serious injury.

For a second, the four of us sat there, stunned. Then we piled out of the vehicle. As I stood up, I could tell that something was wrong with my chest. While I don’t recall its happening, presumably the airbag had driven my laptop into my ribcage. At the moment, I was experiencing only discomfort, but I knew that I had been injured, and it was only a matter of time before the pain would set in. In that expectation, I was not disappointed.

The point of impact for the two vehicles had been headlight-to-headlight at right angles, my Camry’s right headlight connecting with the van’s left headlight.

I won’t go into all the details from here. I will just say that we and the people in the van were very, very blessed. God preserved us, sparing us any real harm, and Shawn pointed out that the prayer we had prayed before we left had been no mistake. What went wrong was obvious, but there was also much that went right, more than we had any reason to expect. It was amazing that we had made it unscathed across the southbound lane in the first place. And the angle of collision couldn’t have been more merciful. Just a second faster or slower for either vehicle would have resulted in a T-bone and almost certainly in serious injuries or fatalities. It was a busy highway; had a semi been coming . . . I don’t even want to think of it.

Huge thanks to fellow chaser Eric Treece, who gave Shawn, Rob, and me a ride back up to I-94, where Rob’s wife picked us up; to Bill Oosterbaan, who came to help and to retrieve his brother, Tom; and to Holly Forry for dropping what she was doing in order to make the long trip out and then drive her husband, Shawn, and me all back to my apartment.

Above all, thank you, Father, for sparing us. Thank you for protecting the innocents in that other vehicle, and thank you for protecting us. Thank you that this Thanksgiving, we have all had much to be thankful for, and that this Christmas, we all will celebrate the birth of your Son, Jesus, once again with our families, as we have done for so many years and hopefully will do for many more.

Accident Corner

About the intersection where our accident occurred: If you go there, you will see that the setup is an accident waiting to happen, and many accidents have in fact occurred there. At least, that is what we were told by both the sheriff and one of the ambulance drivers. I don’t recall seeing a “Stop Ahead” sign, and the other guys maintain there was no warning. Logic tells me that surely there had to have been one, but all I remember seeing was a yellow RR crossing sign as we approached the tracks. That was it.

The tracks were at the top of a rise, and only upon crossing them do you see the stop sign, the side road, and the highway down below. The proximity of the intersection to the tracks comes as a shock (unless, of course, you live in the area), and you’ve got little room to respond. In other words, it’s a horrible setup that is perfectly engineered to catch motorists off-guard. It’s lethal in wet weather and has got to be a terror in the winter. According to one of the guys, the sheriff had mentioned that his department had been after the county to improve the intersection because of the danger it posed, but so far the county had done nothing about it.

So I can’t be too hard on us. But I can’t be too easy, either. We were going too fast for conditions, and I wish I had told Rob to slow down; it was my car and my responsibility to say something. I’m so glad everyone came out of it okay. Banged up and hurting, definitely, but no one in our vehicle or the other one sustained serious injuries or went away in an ambulance. I thank God, most sincerely, that all of us experienced the very best possible outcome of a very bad scenario.

A Word to the Wise (and the Not-So-Wise)

Now, here is what I want to say to all of my fellow chasers: It could have been worse, and it could have been you.

Watch your driving.

My main fear in storm chasing has never been the storms. It has been hydroplaning or otherwise losing control of the vehicle on wet pavement. It is the thing that happens to people who think it won’t happen to them.

I consider myself a cautious driver. Next to some of you, I come across as the little old guy wearing the brown suit and hat who putters along at 45 miles an hour down the Interstate. However, most of the time, I’ve been a passenger, not the one who has driven on chases, and over the years, I have witnessed driving habits that frankly have scared the crap out of me: Chasers rocketing along at 80 miles an hour down wet, curvy, hilly, unfamiliar backroads. Drivers multitasking with cell phones, laptops, and so forth. I can say something about these things to the guy behind the wheel, but that’s the extent of it. I can’t control another person’s behavior. The only thing I can control is whom I get into a vehicle with. And that decision is one I will be taking very seriously in the future, because the attitude that person has toward safety can have huge implications for me, those who love me, other passengers, and other motorists who share the same road. Sitting in the passenger seat three weeks ago, I took the main force of the collision, and never again do I want to go through the pain I’ve experienced these last few weeks as a result. And never again do I want to put Lisa through the shock and fear of that awful afternoon, let alone something far worse.

Some of you take huge risks both with the storms and with your driving. And yes, I know: You’re big boys and girls and it’s your decision. It’s a matter of personal choice. Rah, rah and a fist bump for rugged individualism. We’ve all heard it. It’s like a mantra among today’s chasers.

But when something serious happens to you, trust me, you’ll be singing another tune. Because you don’t really know the the implications of your choices until one of them blasts past your bulletproof attitude and inserts itself into your life with jarring and possibly irrevocable immediacy. There goes the storm you were chasing, receding to the east. But what has just happened to you–that may never go away.

Most of you are in your twenties and early thirties. Lots of life still ahead of you. Many chases still in store for you. Don’t blow it. Because if you wind up in a wheelchair for the rest of your life, the best of your chases will leave you with just a handful of memories and decades of wishing you’d been wiser in the way you went about doing things.

Am I saying you shouldn’t take risks? Of course not. Everything worth doing involves some kind of risk. You can’t truly live without risking. But there is a difference between taking judicious and necessary risks versus taking irresponsible, selfish, and totally avoidable risks. Risks that could get you killed. Risks that could get your chase partner killed and leave you haunted with guilt the rest of your life. Risks that could leave you or someone else paralyzed. Risks that could devastate those you’ve left behind–your spouse or significant other, your children, your parents, your siblings, your friends.

The people you say you love and care about.

Other people and their families.

It ain’t all about you.

When I arrived home at 11:30 that night, Lisa greeted me at the door. I’d never seen her act the way she did–one minute laughing, the next minute crying. Gently, she helped me remove my shirt, a painful operation. We stood in the bathroom in front of the mirror. I was pretty banged up. She kept touching me and kissing my shoulders. She laid her head on my shoulder, closed her eyes, and smiled, and I looked in the mirror and smiled back at her from the glass. My woman. “You’re here with me now,” she said. “That’s all that matters. You’re here with me now.”

I knew then just how much she really loves me, how much I mean to her. I can say, in all truthfulness, that it was worth the loss of my car to experience how much closer the accident has drawn us since that awful day. We almost lost each other. But we didn’t. And during the course of my healing, she has taken care of me beautifully. We have laughed (Ouch! It hurts to laugh!), and had deep, heartfelt conversations, and walked with each other through yet one more stretch of deep water. God has brought us through, and as I emerge on the other side, it is with the certainty that he has given me a truly wonderful, beautiful woman who loves me with all her heart. I have much to be grateful for.

To sum it up for you, my fellow chasers: Chase with passion. But also chase responsibly, with wisdom and an awareness of just how vulnerable you are. Because you are vulnerable. And I think that many of you don’t understand what that means. You say that you do, but do you really? Your life truly is a vapor, as passing as those towers of convection which seem so indomitable in the moment but vanish within hours. Today’s chase will be only a memory tomorrow. Chase in a way that does not become a lifetime of regret, whether for you or those who love you.