The drive down to the WFO at State College, Pennsylvania, was well worth my while (see my previous post). Operational forecaster and research meteorologist David Beachler was a pleasure to work with–personable, patient, and eager to help me understand the exhaustive forecast simulations he had produced on the 1965 Palm Sunday Tornadoes. Having pored over the data with David, gaining his insights on its strengths and weaknesses, I am now extremely excited about what I’ve got on my hands.

David’s modeling uses the WRF-ARW 40 km. The resolution is too coarse to offer the fine details that the SPC is capable of producing, but it gives an excellent overall feel of what forecasters and storm chasers might see in the models if the Palm Sunday synoptic setup were to unfold today instead of forty-five years ago in 1965.

no images were found

There’s no way I can begin to cover all the material, which in any case I need to sift through in order to put together a reasonably concise and meaningful scenario. But I can at least give you a sample of some of the stuff I’ve got to work with. Click on the following images to enlarge them.First, here is a hand analysis of the kind that is accessible to anyone through NOAA’s historical daily weather maps archives. Besides the surface map for April 11, 1965, you also get the previous day’s surface map, 500 mb chart, and other info. It’s what you would have encountered when you turned to the weather page in the newspaper that morning.

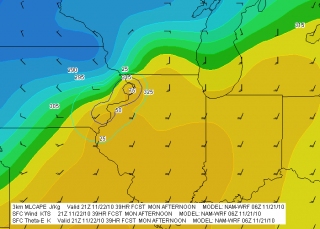

What you would never have seen–because parameters such as CAPE, CIN, helicity, and so on didn’t exist back then, and because even if they had existed, the forecast models which could have depicted them were still years down the road–is this map showing SBCAPE and low-level shear.

The map is for 2200Z, or 6 p.m. EST–roughly the time at which tornadoes began moving through northern Indiana.

It gets even better. Here is a model sounding for KGRR, also at 2200Z, using WRF-ARW Bufkit data. The skew-T and hodograph depict the conditions that were shaping up to produce the F4 Alpine Avenue tornado that formed

around 6:50 p.m., as well as other tornadoes in west and southwest Michigan that day. The helicity is impressive–and look at those winds! Forty knots at 850 millibars is no mere puff of air.What really excites me is that, using RAOB’s cross-section feature, I should be able to reconstruct a vertical profile of the atmosphere for the entire outbreak area. I’m not sure how deeply I want to go with that, but I have the capacity.

Bear in mind that I’m just showing a couple of representative glimpses derived from a 00Z, day-one model initiation. In fact, David provided me with a range of initiation times that allows me to get a good sense of how the maps might have progressed from several days prior to the actual tornado outbreak.

In practical terms, the maps and model sounding data I’ve got correlate to the NAM. They’re not the NAM, but for storm chasers who typically work with the GFS, ECMWF, GEM, NAM, and RUC, what you see here is probably closest to what you’d find using the North American Mesoscale Model.

That’s all for now. This has been a time-consuming post, and at 2:30 in the afternoon, I need to pull away from it so I can bathe and eat. I didn’t arrive home until 3:00 a.m., so it’s time for this road warrior to reset his time clock and get on with the rest of life.