In his recent guest article on Stormhorn.com, my esteemed colleague Kurt Ellenberger explained why he dislikes–nay, loathes, abhors–soloing over rhythm changes.

By George, I enjoy calling Kurt that: “my esteemed colleague.” It sounds so dignified, so prawpuh, so…so pretentious. Hmmm…I relent, Kurt. That description is as cloying as some of the sacred jazz cows that I know you’d like to kebab. So I’ll retract the “esteemed colleague” bit and just call you my friend; a funny, thoughtful, and insightful guy; and, need I say, an absolute monster musician.

But I still disagree with you about rhythm changes.

To an extent, that is. I’ll begin my rebuttal to your post by agreeing with you. Given your musical experience and the high level at which you play, you get to hate rhythm changes to your heart’s content, along with any other musical formulae that you choose. You’ve attained, man. Once a person has mastered the rudiments of jazz to a world-class degree, there’s no need to keep rehashing them. The point of laying a foundation is to build something new upon it, not enshrine it.

This being said, foundations are important, and rhythm changes are an exercise in foundational material. Moreover, whether they’re banal is a matter of perspective.

In his post, Kurt provides an analysis of rhythm changes that emphasizes their mostly static harmonic nature, with the exception of a temporary digression to the circle of fifths at the bridge section, which Kurt labels as trite. Overall, he is unimpressed by RCs.

But “trite” is simply a viewpoint, and viewpoints are personal. Some perspectives change as an individual accumulates experiences, while others deepen as time helps to clarify and reinforce them. This, I think, is the heart of the matter. As Kurt puts it, following his analysis, “In general, I prefer music that has a higher degree of harmonic activity and direction, or, absent that (as in music of a more minimalist nature, much of which I enjoy tremendously), there must be some other complexity in play to retain my interest. These preferences have become more pronounced over the years. As a result, I’ve lost interest in a lot of tunes that are similar in construction.”

Note the words “prefer” and “preferences.” They are personal terms. Everyone is entitled to his or her preferences, but one’s reasons for them are not necessarily a definitive yardstick for determining the value of a thing, particularly when other criteria can also be applied.

If I ever attain to Kurt’s level of harmonic and overall musical sophistication, then perhaps I’ll feel as he does about rhythm changes and the 32-bar song form overall. Probably not, though. Rhythm changes just never bothered me at the onset the way they did Kurt. But then–and this should come as no surprise–I see them in a different light.

For one thing, I’m a saxophonist, and as such, my concerns as they apply to my instrument are purely melodic. By this I don’t mean that I’m uninterested in harmony–I’m keenly interested in it, of course–but rather, that I’ve only got one note at a time at my disposal, not entire clusters. This alone creates a different outlook than Kurt has as a pianist.

For another thing, I’ve taken a different and slower developmental path than Kurt’s. For still another, I’ve worked on rhythm changes by choice, not because of an educational or cultural mandate. Finally, I’m me, with my own set of preferences and dislikes. And on both artistic and practical levels, I find playing rhythm changes to be enjoyable, valuable, and, yes, challenging.

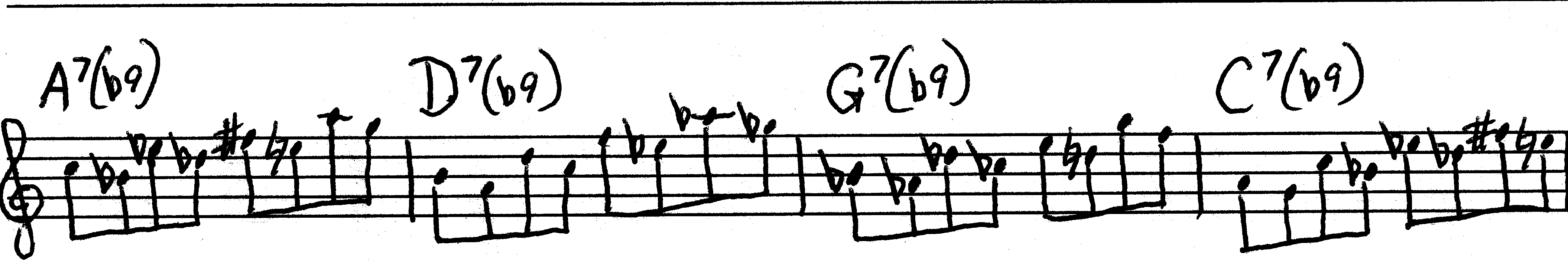

On the practical level, rhythm changes are a great way to take rudimentary elements of improvisation such as turnarounds, cycles, and ii-V7s out of isolation and set them in an applied context. I’ve already addressed this matter in my original post on rhythm change, so I won’t rehash it here. The points I made then remain valid. From a developmental standpoint, RCs are–like that other even more foundational form, the blues–good for you. You don’t have to build your world around them, but learning how to play them well gives you some substantial building blocks which you can adapt in other ways that may interest you more. As a musical exercise, I view rhythm changes in somewhat the same category as scale work and etudes.

As a young improviser, I first began to make the leap from technique to musicality by memorizing a Charlie Parker solo based on rhythm changes. Today, I’m still finding RCs invaluable for helping me to build my chops in different keys. I’m convinced of their value. A raftload of Charlie Parker contrafacts can’t be wrong.

However, those same Charlie Parker tunes are now very old, and jazz has traveled in a lot of directions from its 1940s bebop watershed. Bird himself, in the final years of his life, felt that he had taken bebop as far as he could and was seeking a new direction. Which brings me to the artistic aspect of rhythm changes.

Rhythm changes, banal? I suppose they can be, but I don’t think they have to be. Listen to Michael Brecker ripping through “Oleo” and tell me that’s banal. The difference lies in Michael’s approach. He’s not merely regurgitating old licks; he has developed his own voice and is applying it masterfully to the changes. Michael certainly doesn’t seem disenchanted.

While I can’t say for sure, I suspect that the late tenor master had absorbed so much music of all different kinds that he didn’t much care whether he was playing a sparklingly contemporary, harmonically complex tune or an old chestnut. Like Kurt, I’m sure that Michael had his preferences, but that didn’t keep him from weaving magic with rhythm changes and, to all appearances, enjoying himself in the process.

Kurt mentions getting locked into a formulaic approach to RCs. I know what he means–I face that same challenge. But since I don’t have an innate bias against rhythm changes, I view the rote licks and patterns as just a framework which, as I master it, can ultimately enable me to move beyond it. Kurt knows, far better than I, that rhythm changes, like any tune, can be altered in creative ways that are only limited by one’s imagination.

And, I might add, by one’s level of interest. If a player isn’t motivated to explore the possibilities, then rhythm changes, like any well-worn standard in the American songbook, will indeed become banal through over-repetition of the same-old-same-old. I fully concur with Kurt that there has to be some level of complexity present, some kind of intellectual and/or technical challenge, to hold my attention.

However, I maintain that the potential for such complexity exists in any tune. I mean, how innately fascinating is a Dorian mode? But we understand that there’s a whole lot more to modal music than a single scale played ad nauseum over a single minor chord. It’s not a matter of what you’re given, but of what you do with it and, I should add, whom you do it with.

I could say more on the matter, but there’s no point in doing so since it really does boil down to a matter of personal preference. Instead, I have a couple observations to make with which I think Kurt will fully concur.

First, while I’m obviously a proponent of rhythm changes, I would emphasize that they’re just a stopover on a much larger musical journey. I think it’s wise for a developing jazz musician to go through them, it’s helpful to camp out on them for a season, and it’s fun to return to them and enjoy the view, but for goodness sake, don’t buy a house there. The neighborhood is already 80 years old and the heyday of its development in the bebop era is long past. Use what’s been done as a basis for finding your way toward newer, more personal musical directions.

Second, jazz traditions may be venerable but they’re not sacred, and this certainly applies to rhythm changes or to any musical form. It’s okay not to like them and it’s okay to say so.

Jazz culture has been a breeding ground for some affectations and norms that I don’t much care for. Some of them may have served a purpose at one time, but, as Kurt has done a great job of pointing out in a post titled “Jazz in Crisis” on his own blog, Also Sprach Frackathustra, they’re now outdated in a larger world that has moved far beyond the jazz era.

So let’s be real. If jazz is about freedom, as we say it is, then saying that one doesn’t care for rhythm changes shouldn’t require some sort of hush-hush, confessional tone for fear that Big Brother is listening. I’ve never been aware of such a cultural pressure, but I don’t doubt that Kurt has experienced it, and that bothers me. Good grief, we’re talking about a set of chord changes, not the Ark of the Covenant.

Many of us jazz practitioners need to distinguish between the true non-negotiables of the music we play versus the affectations and cultural mores that surround it. If we don’t search our own souls, believe me, the rest of the world doesn’t care enough to do the job for us. Many of us could start by dropping our smug, musicianly superiority and becoming just plain, down-to-earth, nice people who treat both our fellow musicians and non-musicians graciously.

With that, I think I’ve worked the rant out of my system. Kurt, I guess I’ll continue to enjoy playing rhythm changes, at least until, like you, I experience them as more limiting than beneficial. Until then, I promise, cross my heart, that if you and I do a gig together, I won’t call for rhythm changes.

However, if I catch you playing solo somewhere, I may request “Anthropology” just to see you wince.

ADDENDUM: Be sure to check out the final installment of this series, in which Kurt offers his own closing thoughts.