A while back I shared some ideas on how jazz improvisers can make optimal use of the added flat sixth tone of the major bebop scale. I pointed out that, besides its obvious use as a passing tone that evens out the scale and allows players to move seamlessly from root to octave (or third to third, or fifth to fifth, etc.), the flat sixth also functions readily in a number of harmonic contexts common in jazz.

Yet, useful as the flat sixth (or sharp five) of the major bebop scale can be, it is nevertheless only one of five non-diatonic tones that occur in a major key. In addition, the tonic, supertonic, subdominant, and submediant scale degrees can all be similarly raised a half-step and used in a variety of harmonic applications.

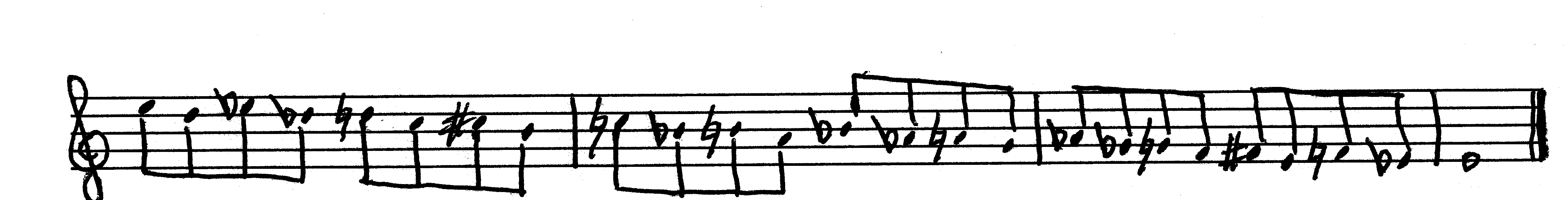

The image to your right is a table that shows some common uses for each non-diatonic tone in the major scale. (Click on the thumbnail to enlarge it.) The table is by no means exhaustive; it’s just meant to give you a handy reference to harmonic situations you’re likely to encounter as an improviser.

The image to your right is a table that shows some common uses for each non-diatonic tone in the major scale. (Click on the thumbnail to enlarge it.) The table is by no means exhaustive; it’s just meant to give you a handy reference to harmonic situations you’re likely to encounter as an improviser.

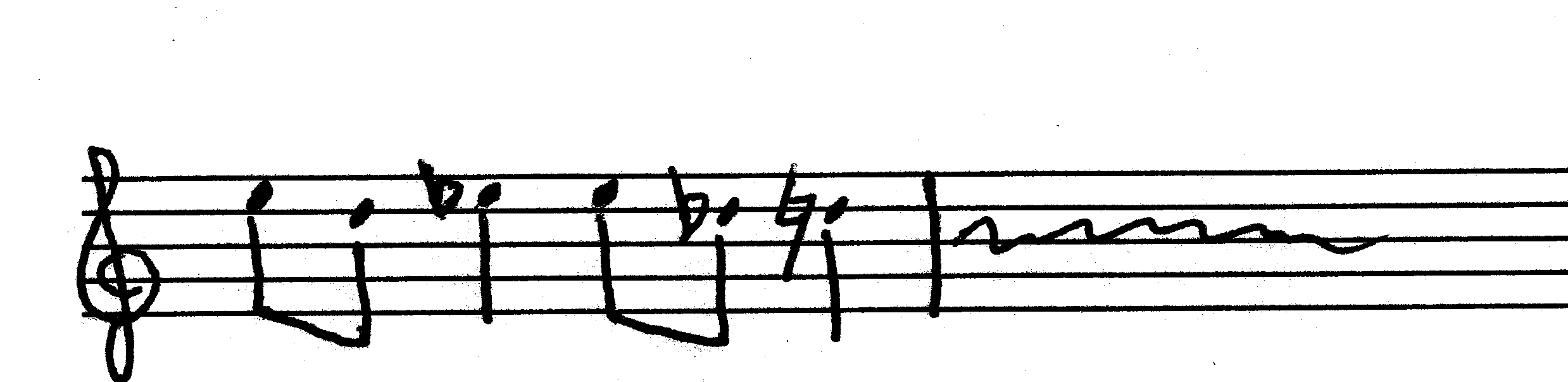

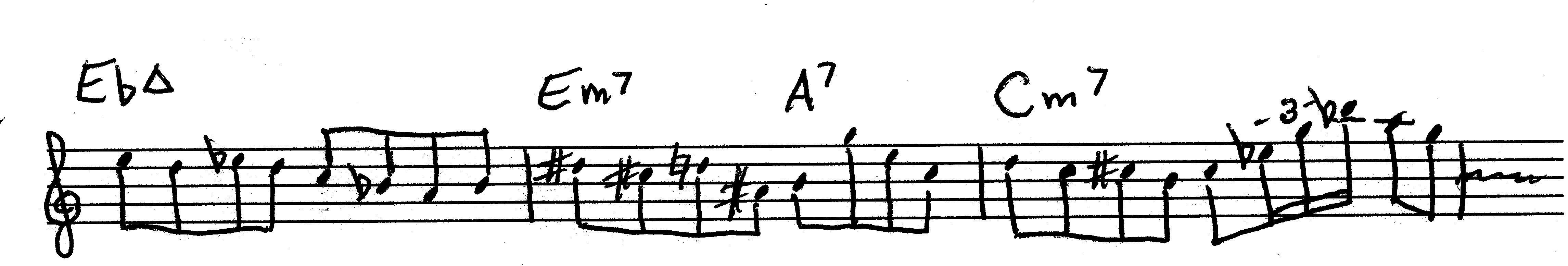

The table is based on the C major scale. In that key, the five non-diatonic tones are C#, D#, F#, G#, and A#. From top to bottom, the staves begin with a given tone, then show how that tone fits into various chords. The chords are numbered according to their functions and also named (eg. IVmin7, Fmin7). Depending on their application, I may use the enharmonic equivalents of some tones. For instance, instead of A#, I’ve chosen to show Bb, which makes better sense in actual usage.

In stave 1, the VI7b9 and #Idim7 are interchangeable, leading almost inevitably to the IIm7 chord. In the next stave down, the #IIdim7 wants to resolve to the mediant. By adding the scale’s leading tone as the chord root, you wind up with a B7b9, which is the V7 of III. Glancing over the rest of the table, you’ll notice numerous other uses in secondary dominant harmony.

I’m not going to go into detailed explications of every chord, as–assuming that you know your basic jazz theory–the uses of the different non-diatonic tones should be self-evident. Again, the table is not definitive. It’s intended simply to give you a handy reference that can heighten your awareness and help you make more deliberate use of all twelve tones in the chromatic scale. You’re bound to think of other applications not shown in the table.

For practice purposes, you could try working with a single tone. Incorporate it into a major scale to create an eight note scale. Then work out various chordal possibilities that utilize the tone, always keeping in mind the parent major key you’re working in as a frame of reference.

If you’ve found this article useful, make sure you check out the many other articles, exercises, and solo transcriptions on my jazz page. And, as always, practice hard and with focus–and have fun!