Sometimes a picture really is worth a whole lot of words. In this case, two tell the story more eloquently than I can.

Sometimes a picture really is worth a whole lot of words. In this case, two tell the story more eloquently than I can.

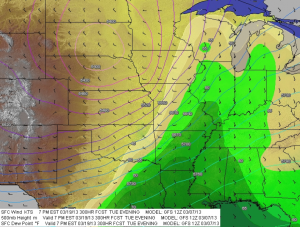

In the image to your left, the 12Z run of the GFS depicts 500 mb height contours, surface moisture, and surface winds at 300 hours out, or twelve days before the forecast date.

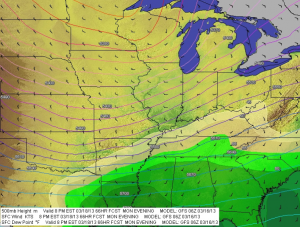

The second image, taken just a little while ago, shows the same information for the same system, only now we’re down to just 66 hours from forecast time. Note that the forecast date has moved up a day to Monday; by Tuesday, the whole system has moved off to the east and out to sea. Bye-bye moisture and instability.

What happened? The GFS happened, that’s what.

What happened? The GFS happened, that’s what.

I realize that for many of my storm chasing readers, maybe most of you, I’m preaching to the choir, but some may wish to take note of the following:

Long-range forecast models are notoriously undependable and prone to change.

If you’ve never heard the colloquialism wish-casting, now’s the time to add it to your storm chasing lexicon. The further out you go beyond three days from an event, the more that attempting to forecast a chaseable setup amounts to just a hope and a prayer. Bad data and changing data amplify progressively in the numerical models, to the point where what you see at 240 hours out is subject to anything from mild to wild fluctuation and revision as the forecast hour draws closer and new data gets processed. By the time the NAM and SREF lean in, and finally the RAP and HRRR, what you see may resemble nothing like the deep, negatively tilted trough and gorgeous moisture plume that first captured your attention. The shape, the timing, wind speed and direction at different heights, quality of moisture, instability–everything can change, and it will, possibly quite drastically.

Remember the gossip chain? Anna tells Peter, “Selena just bought a used Nissan from the same car dealer where Jaden bought his truck. It’s on 44th Street about a mile from the dump.” Peter passes the news on to Sam thus: “Selena just bought a car from the same dealer where Jaden got his truck next to the 44th Street dump.” Sam tells Chelsea, and Chelsea tells Adam, and so it goes, with the information getting nuanced a little more each time until it becomes outright twisted. Finally, word gets back to Selena: “Hey, Selena, what’s this I hear about you buying the dump over on 44th Street from some drug dealer?”

It can be kind of that way with long-range forecasts.

So why even bother watching the long-range models, particularly the famously untrustworthy GFS? There are two reasons. One is, the models can provide a heads-up to the possibility of a chaseworthy setup. At 192 hours out, don’t think of the models as forecasts–think of them as potential forecasts, something to keep an eye on. A given scenario could fall completely apart and often does. But it could also develop run-to-run consistency that agrees with the short-range models as they enter the picture, and ultimately lead to a decent chase.

For those of us who have to drive a long distance to Tornado Alley, such advance awareness is particularly valuable. If you live in Chickasha, Oklahoma, or Wichita, Kansas, you can roll out of bed in the morning, look at the satellite, surface obs, NAM, and RAP, and decide whether you’re going to chase in the afternoon. But if you live in Grand Rapids, Michigan, or Punxatawney, Pennsylvania, things aren’t that easy. When you’ve got to travel 800 to 1,000 miles or more to get to the action, burning time and fuel and perhaps vacation days, lead-time becomes important, and the more, the better.

The second reason for watching the long-range models is sheer obsessiveness. Call it desperation if you wish. It has been a long winter and storm chasers are itching to hit the road. Some of us just can’t help ourselves–we want to see some flicker of life, some sign of hope, some indication of the Gulf conveyor opening for business beneath a warming sun and dangerous dynamics. What’s the harm in that? Most of us know enough not to hang our hats on a 120-hour forecast, let alone one that’s two weeks out. But it doesn’t hurt to dream. After all, sometimes dreams come true.

I never knew weather could be so interesting! Good point about our natural curiosity about the future, I’d never thought of the long-range forecast like that before. Thanks for the interesting perspective!

It’s good to hear from you, Karen! Weather is indeed fascinating–or at least, I find it so. Yes, the farther out a forecast goes, the likelier it is to change. That’s just how it is. The forecasts are largely based on what are called “numerical models,” or just models, each of which has its strengths and weaknesses. One component of forecasting is comparing the various models to see which currently has the best handle on an evolving weather system. NOAA even publishes a daily discussion. And at the end of it all, your picnic plans for a week from now may still get rained on.

Good write up as always. I tend to cut the GFS a little more slack than most. Using the 2 examples above I think thats a pretty good verification. Yea at first you might look at those and think whaaaaaaat theyre nothing alike but when you take a step back and look at the big picture the model, at 300 hours out had a general idea where would be some sort of trough in that general area. Now if the 66hr plot was a huge 588 ridge, I would call that a fail.

IMO long range forecasting is more about the general pattern as opposed to the details of each setup. People who have more realistic expectations of what to expect often do better after observing trends in the models. You sometimes pick up on things that raise flags to lend or take away credibility on a particular run.

I have to agree with you there, Adam. You’ve cut to the core of why any of us consult the long-range models so far out: they can give us a valuable heads-up to broad patterns that may hold together–sometimes, and sometimes not–even as other features slosh around. The map most people watch is the 500 mb heights map. If a trough crops up and manages to keep cropping up, then you know you’ve probably got something. Trying to figure out the details is pointless until the forecast hour draws closer, but you get a sense that there could at least be details.

It all depends on what you look for. As I think of it, the two examples I used demonstrate both the usefulness and the uselessness, the consistency and the inconsistency, of the GFS, all hinging on one’s focus. For me, the bottom line is, it’s always worth watching to see how things will pan out. Living in Michigan, I’ll take as much lead time as I can get. A healthy dash of hope doesn’t hurt matters either.