What? Another Stormhorn post so soon?

Yes, I’m on a roll. This post is a continuation from the last post, which offered a couple practical exercises on angular playing using pentatonic scales. As I promised in that post, this next one explores the relationship between pentatonics and altered dominant harmony. But as with the previous post, my objective here is not to go all theoretical on you but to offer a few practical exercises for developing facility with pentatonics in the V7 alt context.

Still, for these exercises to make sense, a bit of theory is necessary. By altered dominant, I’m referring to the V+7(#9) chord, otherwise known as the V7 alt. Jamey Aebersold long ago introduced the simpler spelling V7+9, and since that’s the one I’m used to and it’s convenient, that’s the spelling I’ll use. The chord is called “altered” because very little about it–just the root, third, and flat seventh–is unaltered. The fourth and fifth are both raised a half step, and both sharp and flat ninths are included.

The scale of choice for the V7+9 chord is the diminished whole tone scale (dim WT). It is actually a mode of the melodic minor scale built on its seventh degree. For example, a B dim WT is built off the C melodic minor scale, thus: B, C, D, Eb, F, G, A, and octave.

Within the dim WT scale lies a single major pentatonic scale built on the scale’s tritone (augmented fourth).* So, again using the B dim WT as our model, the resident pentatonic is F: F, G, A, C, D. These notes constitute all the scale’s altered tone plus the flat seventh, thus: +4, +5, b7, b9, #9.

For me, the question is, how do I relate the sound of a major pentatonic scale to an altered dominant whose root is a tritone away? It’s not a sound that sticks readily to my ear.

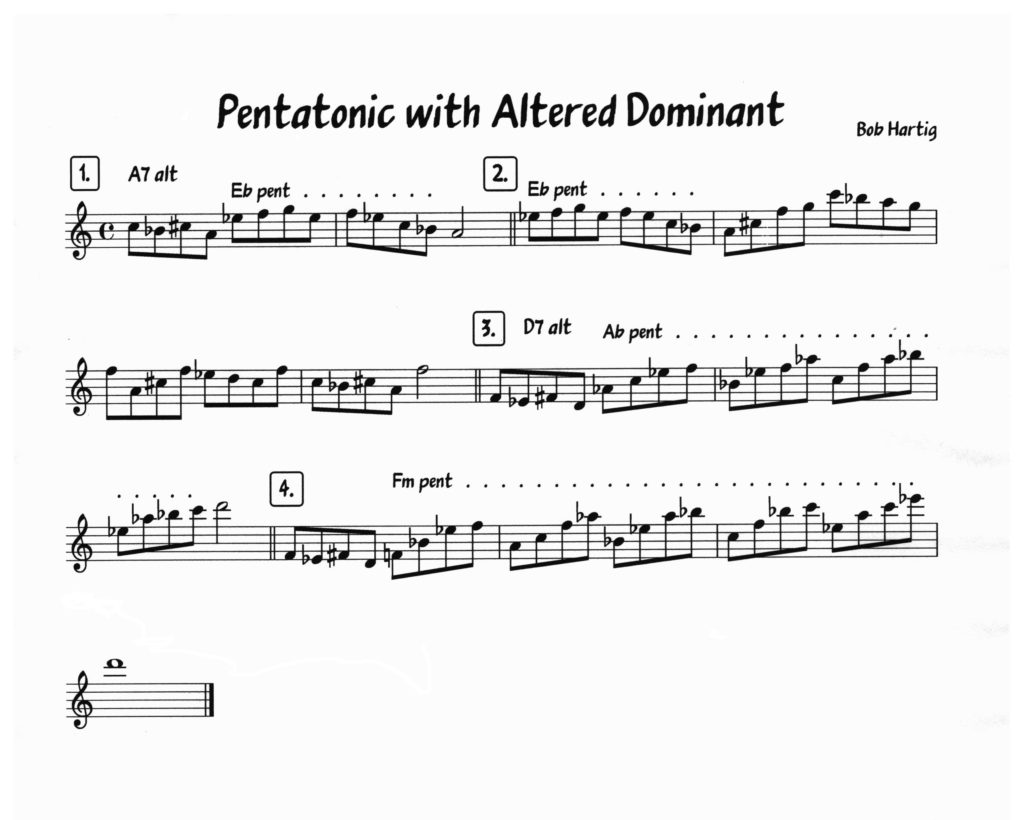

The four exercises shown here–licks, really–are designed to help you drill your fingers and ears on the dominant chord and corelate them to the pentatonic scale. To my thinking, at least at this stage in my development, I want to resolve the pentatonic scale to one of the basic chord tones, and I want to have those chord tones–the root, third, augmented fifth, and flat seventh, always in mind.

To that end, the first exercise introduces a motif I also use in the rest of the exercises. It focuses on the lower part of an A7+9 chord, starting with the sharp and flat ninths and then establishing the third and the root. Following that little four-note figure is a well-known pentatonic lick based on the tritone, Eb. Finally, the exercise resolves to the root of the chord.

Exercise two starts with the pentatonic lick, then arpeggiates the A7+9 and explores the dim WT more fully, and concludes with the four-note motif, described above, resolving to the sharp five of the chord.

The third and fourth exercises, now focusing on the D7+9, begin with the motif, then move into more angular versions of the pentatonic scale. Note that in the fourth exercise, I’ve opted to focus on the F minor pentatonic. It is the relative minor of the Ab major, so none of the notes involved have changed; it’s just a different way of thinking about the pentatonic scale.

I recommend that you spend some time with each exercise in just the key it’s written in, playing it slowly and trying the absorb the sound of the pentatonic scale in relation to the sound of its parent dim WT scale and the V+7 chord. Then work at memorizing each lick in all twelve keys.

That’s it. They rest is up to you. I wish you fun and fruitful practicing.

ERRATUM: In exercise four, the first note in the second bar should be an Ab, not an A natural. With this post finally put to bed, I don’t have the patience to spend the time required (more than you’d believe) to add a lousy little flat. So kindly make the adjustment mentally.

___________________

* You could argue that there are other pentatonics that also fit the altered dominant chord. True, but they’re all modified in one way or another. The only natural major pentatonic that derives from the diminished whole tone scale is the one I’ve described.