When was the last time I shared a practical exercise for jazz improvisation on Stormhorn.com? It has been ages, hasn’t it.

So let me rectify that as best I can by giving you something substantial to chew on, or better yet, to take to the woodshed with you and work into your fingers and your playing.

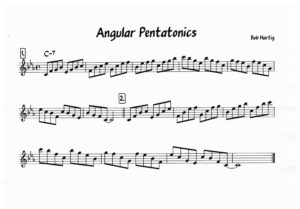

Lately I’ve been revisiting pentatonic scales, with an eye on two things: (1) their usefulness in angular playing, and (2) their relationship to altered dominants. I’ll look at item two in a future post. Right now, let’s turn our attention to pentatonics as a source for angularity–that is, breaking out of the linear, scalar mode of playing by using broader intervals, particularly fourths, to create novelty and interest.

You can think of a pentatonic scale as a major scale (or a mixolydian or lydian mode) with a couple teeth knocked out. The fourth and seventh scale degrees are missing, creating a five-note scale with a couple built-in gaps. Those two gaps, as you begin to work with intervals in the scale, create broader leaps, and angularity arises naturally.

The two exercises in this post will help you build technical finesse with broader intervals in the pentatonic scale. Work out the first exercise till you’ve got it mastered in all twelve keys throughout the entire range of your instrument. Then move on to the second exercise and do the same, revisiting the first as you need to in order to help it “stick.”

Both exercises are built off of the relative minor of the Eb major pentatonic scale. I’ve assigned them to the C-7 chord; however, you can also use them with the EbM7 and Eb7 chords, as well as a few other chords which I’ll leave it to you to work out in your head and your playing. My concern here isn’t to deal in depth with theory and application but simply to give you something you can wrap your fingers around. You can trust I’m doing my best to gain command of them too. We’re traveling this path together. Practice diligently–and, as always, have fun!