Lately my practice sessions have involved both the diminished whole tone scale and the pentatonic scale. There’s a reason for this: the two are related, and both scales go well with the V+7#9 chord. My previous post explored how this plays out with a basic major pentatonic scale. I worked with mode 4 of that scale, starting on the b9 of the V+7#9 chord. In root position, the scale would actually begin on the +4 of the chord.

Today during my practice session I focused on another pentatonic scale rooted on the +5 of the V+7#9. It’s a wonderful sound that really brings out both the major third and #9 of the chord as well as the evocative color of the raised fifth. This scale is not your standard-issue pentatonic; its flatted sixth gives it a mysterious augmented quality.

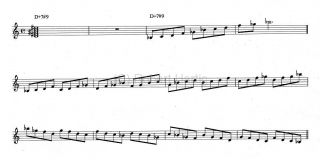

Click on the image to your right to enlarge it. The first thing you’ll see is a D+7#9 chord outlined in whole notes. To its right is an ascending Bb pentatonic scale with a flatted sixth. You’ll see how the scale is entirely consonant with the chord. Moreover, further analysis will reveal that the Bb pent b6 is actually an abbreviated form of the D diminished whole tone scale.

Still more interesting is the fact that the Bb pentatonic scale with a flatted sixth actually is the D+7#9! It’s what you get when you scrunch all the chord tones together linearly (or as near linearly as possible). While I’d love to make myself sound like a master theoretician who has known this fact for most of his musical life, the truth is, I just made the discovery a little while ago. Now I know why this scale sounds so great when played with the altered dominant chord. It is the chord.

Of course the scale has other applications besides the V+7#9, the most obvious being major and dominant chords that share the same root as the scale. I’ll let you work out the various other harmonic possibilities for yourself as they’re not the focus of this post.

Back to the image: The second and third lines introduce you to a basic exercise that will help you start getting your fingers around the pentatonic b6 scale. It would be most helpful if you had some kind of accompaniment sounding the chord when you work on this pattern. You want to internalize the sound of the chord-scale relationship, not just the technique.

It goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: Take this exercise through the full range of your instrument and learn it in all twelve keys.

And that’s that. For lots more chops-building exercises, solo transcriptions, and information-packed articles, visit my jazz page.