This post builds upon a jazz improvisation post I wrote a month ago titled Fourth Patterns: Three Exercises to Build Your Technique. That post gave you some quartal patterns to practice that took you around the cycle of fifths. While I pointed at the harmonic possibilities, I left you to sort them out for yourself. In this post, I’m providing a specific application by applying fourth groupings to altered dominant chords (V+7#9).

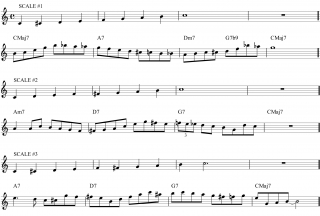

Click on the image to your left to enlarge it. The first thing you’ll encounter is a brief exercise that takes you through a fourth pattern moving by whole steps, first down, then back up. It’s a simple exercise. Once you’ve got it down, practice it starting on the note F instead of Eb; you’ll be using the same notes you’ve already practiced, but you’ll reverse the direction of the patterns.

From there, play the same exercise starting on the note E. You’ll now have a different set of notes. Finally, start on the note F#. Once you’ve worked that into your fingers, you’ll have covered all the possibilities.

Moving On to Application

The material you’ve just practiced is designed to help you develop technique specific to the application that follows. Now we’ll move on to that application, as indicated by the chords.

For each chord, you’ll find two groupings of the fourth pattern spaced a major second apart. Together, the two patterns contain the following chord tones: #9, b9, b7, +5, +4*. The patterns are arranged in eighth notes that resolve to a consonant chord tone, thus:

- • In the first two bars, the b9 resolves to a whole note on the chord root.

• In the second two bars, the #9 resolves to a whole note on the major third of the chord.

I’ve written down the applications for six keys. I’m sure you can figure out the remaining six on your own, and you should. Don’t be lazy! You need to become familiar with all twelve chords. Moreover, I encourage you to experiment with variations on these patterns. This exercise will open up your technique for altered dominants–and other harmonic applications–but you should view it as a springboard for further exploration.

As is so often the case, the material I’m sharing comes to you fresh from my own practice sessions. It’s a chronicle of my personal learning curve, and I hope it assists you in yours.

If you found this article helpful, you’ll find many more like it on my Jazz Theory, Technique & Solo Transcriptions sub-page.

Practice hard, practice with focus–and, as always, have fun!

——————————–

* If you add two more tones–the chord root and the major third–you’ll get a complete diminished whole tone scale. In this application exercise, the whole notes use those two missing tones as resolutions.