Two posts ago, I talked about the use of the sixth as a sort of sweetening agent in improvised solos. If you haven’t yet done so, I recommend that you read that article before proceeding with the following exercises. It’s always good to understand a little about the whys and wherefores of what you’re doing, particularly when it comes to connecting saxophone technique with jazz improvisation.

One thing I didn’t mention in the previous post, and an important point at that, is the angularity that sixths bring to a musical line. Broad interval that they are, sixths are by definition intensely angular, and as such provide a colorful and interesting way to break up a linear flow.

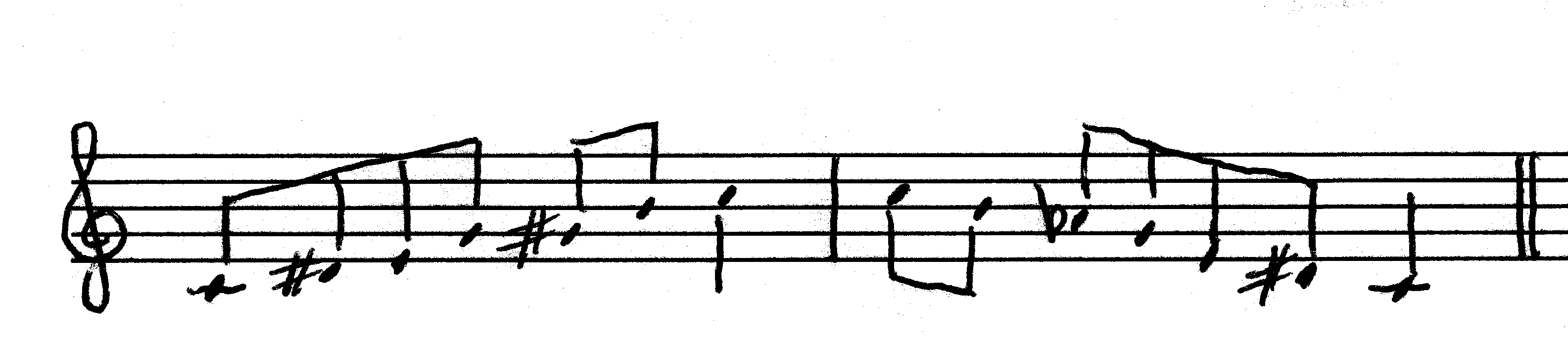

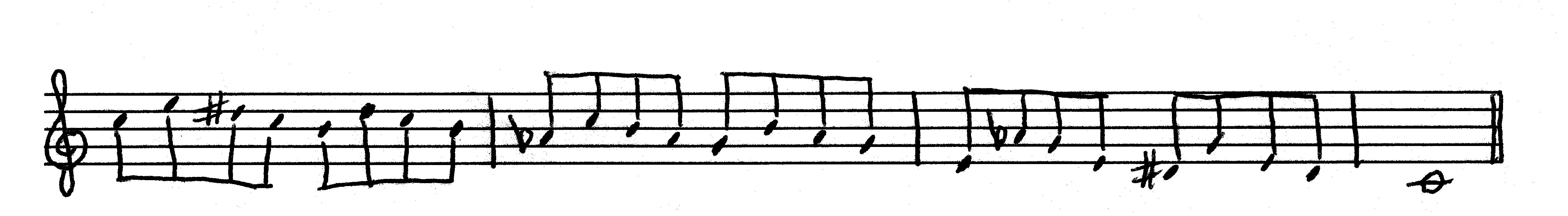

The three exercises on this page are all based on the C major scale. (Click on the image to enlarge it.) The first exercise features basic sixth diads, moving up and then back down an octave.

The second exercise begins on the third of the C major scale (the note E) and moves up a sixth to the tonic C, thereby strongly implying the C major chord and establishing the key center. The exercise moves downward from there, incorporating the added color of passing tones and chromatic lower neighbors.

Exercise three, ascending an octave, approaches each lower note of the diads with a chromatic lower neighbor. While the result is a series of three-note groups, I’ve written the exercise in eighth notes rather than triplets to create a syncopated effect.

Consider each written exercise to be just the abbreviated form of what you actually need to practice. You should take all three exercises up and down through the entire range of your saxophone. You’re smart enough to figure out the missing pieces for yourself, and you should do so.

I suggest that you start by picking one pattern and memorizing it in all twelve keys, beginning with the first exercise. Then proceed to the next pattern and do likewise.

Yes, I know–I’m a drill sergeant and you hate me. But I promise you, all that hard work will pay big dividends with time. One of these days, you’ll thank me. Really. “Thank you, Bob,” you’ll say. Until then, my ego is tough enough to handle the lack of love.