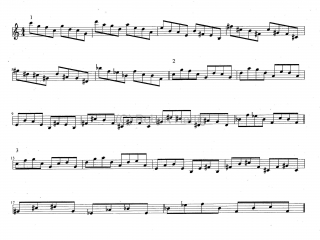

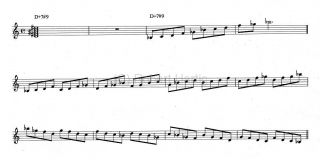

A while back, I wrote a post on the tritone scale. For my second video tutorial, I thought I’d supplement that article with a brief audio-visual clip. Supplement is the operative word. Besides describing the theory of the tritone scale in somewhat greater detail and probably a bit more lucidly than the video, the writeup provides written examples for you to work with. But the video helps you hear the sound of the tritone scale, and in so doing, allows you to come at the scale from every angle.

People’s learning styles differ, so maybe this tutorial will be more your cup of tea. Regardless, if you haven’t read my written article, make sure to do so after you’ve watched the clip.

On a side note, the video was shot out at the Maher Audubon Sanctuary in rural southeastern Kent County, Michigan. I’m discovering a fondness for producing these tutorials in outdoor settings when I can. With winter closing in, my future productions will soon be relegated to the indoors; right now, though, nature is singing “Autumn Leaves,” and it has pleased me to capture a bit of her performance.

If you enjoy this tutorial, check out my Jazz Theory, Technique & Solo Transcriptions page. And with that said, enjoy the video.