Many years ago, when I first became aware of chord superimposition, I hit upon a unique concept. Inspired by my new awareness of tritone substitution, I thought, What would happen if I took two major triads a diminished fifth apart–C and F#, for example–and crunched all the notes together to form a scale? Wouldn’t that be cool!

Of course it had already been done, just not by me. My musical innovations tend to be in the same league as my discovering fire, gravity, the wheel, Chicken McNuggets, things like that. In this case, I had stumbled upon the tritone scale, so named for obvious reasons.

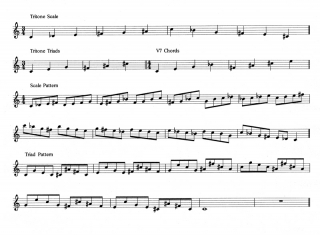

Think of a diminished scale with two notes missing, kind of like a smile with a couple teeth knocked out, and you have the tritone scale. The standard C half/whole-step diminished scale consists of the notes C, Db, D#, E, F#, G, A, Bb, C. If you remove the notes D# and A, the result–as shown in the first example (click to enlarge)– is a C tritone scale: C, Db, E, F#, G, Bb, C.

The tritone scale falls in the class of scales called hexatonic (six-tone), which also includes the augmented, whole tone, and blues scales. Since the tritone scale is derived from two major triads, you’ll of course find those triads contained in it. You’ll also find two dominant seventh chords native to the tritone scale. (See second and third examples.)

The leap of a minor third between the second and third tones, and between the fifth and sixth tones, renders the tritone scale asymmetrical. That asymmetry lends color to the scale and makes it a good source of angularity. By its nature, the tritone scale will make you think a bit differently than you would if you were using a complete diminished scale–with which, I should add, the tritone scale is interchangeable.

The last two examples in the image are actually exercises on the tritone scale. The first is a straightforward scale exercise. The second alternates the two triads that are native to the scale, taking you through their different inversions. As always, play each exercise through the full range of your instrument.

How to use the tritone scale in improvisation

All that theory is fine, but what about actual application? Naturally you want to know how the tritone scale is used.

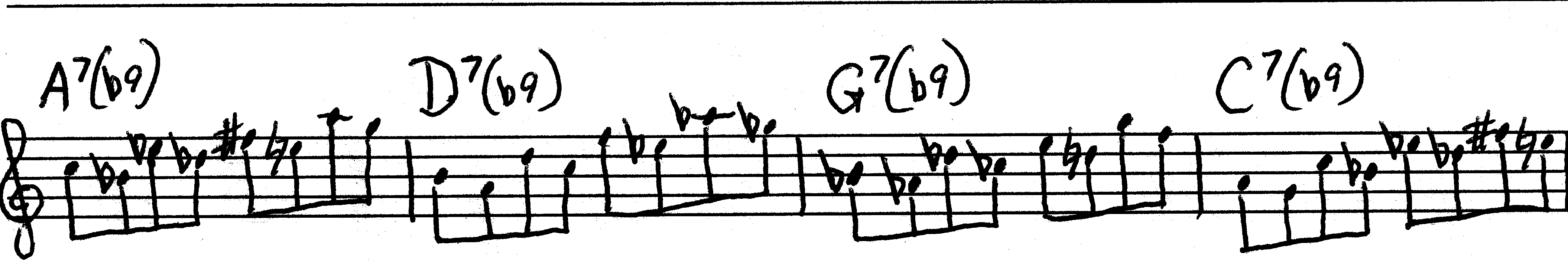

Use it anywhere you would use a whole/half-step diminished scale. The most obvious use is with a V7b9 chord. Since, as I’ve said, the tritone scale is interchangeable with the diminished scale, you can use it with any of four different dominant chords. For instance, you can use the C tritone scale with C7b9, Eb7b9, F#7b9, and A7b9. Note that two of these chords, the Eb7b9 and A7b9, are built upon the “missing notes,” which means you can skate around the chord roots without ever landing on them.

Tritone scales built on the roots of dominant chords pack the advantage of having the tritone substitution built right into them. The second exercise (last example) demonstrates this beautifully and is one you definitely should get under your fingers.

The tritone scale also adds interest to minor scales. Use the seventh of the scale as the chord root. Another way of thinking of it is, use the note that’s a major second above the chord root as the tonic of your scale. For example, if the chord is a Bbmin7, use a C tritone scale.

If you want a good example of the tritone scale in action, the first part of Michael Brecker’s solo on “Quartet Number 3” in the Three Quartets album by Chic Corea is a tritone tour de force.

And with that, I’ll sign off. Practice hard, experiment, and have fun!