Last year’s abnormally balmy March opened for storm chasers with a lion-like roar on the 2nd with a deadly outbreak of tornadoes along the Ohio River southward. But from then on, with the exception of April 13 and 14, the season dwindled into a pathetic, lamb-like bleat.

Last year’s abnormally balmy March opened for storm chasers with a lion-like roar on the 2nd with a deadly outbreak of tornadoes along the Ohio River southward. But from then on, with the exception of April 13 and 14, the season dwindled into a pathetic, lamb-like bleat.

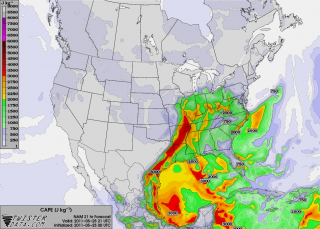

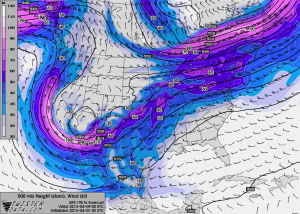

This March has been the polar opposite, and I do mean polar. Many chasers have been champing at the bit due to a wintry pattern that has simply refused to let go. But that may finally be about to change, and April may be the month when this year’s chase season starts to howl. For the last several days, I’ve been eyeballing a large trough on the GFS that wants to invade the Great Plains around April 8, shuttling in Gulf moisture and also suggesting the possibility of warm-front action farther east on the 9th.

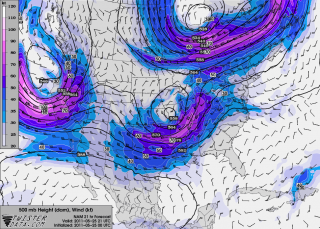

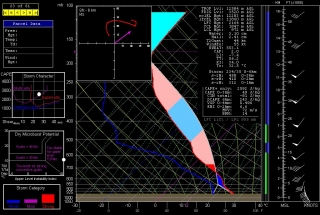

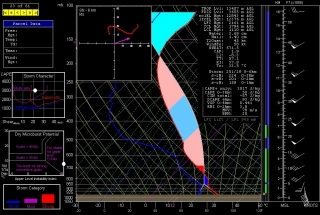

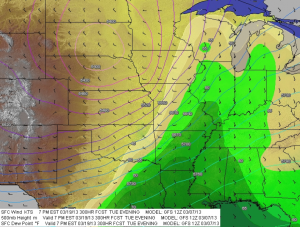

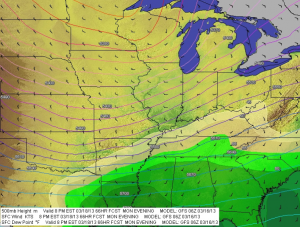

The ECMWF broadly agrees. The first map (click to enlarge), initialized today at 00Z, compares the 168 hour forecasts for GFS and Euro heights for Sunday evening, April 7 (00Z April 8). The second map, from TwisterData, depicts the GFS 24 hours later at 7 p.m. CST.

The ECMWF broadly agrees. The first map (click to enlarge), initialized today at 00Z, compares the 168 hour forecasts for GFS and Euro heights for Sunday evening, April 7 (00Z April 8). The second map, from TwisterData, depicts the GFS 24 hours later at 7 p.m. CST.

Maybe not a poster child for negative tilting (though the 6Z run changes that), but it could signal the breaking of the Champagne bottle against the hull of chase season 2013. The details will fill themselves in as the forecast hour narrows down. Right now, this is a hopeful sign for storm chasers. Winter may still have a gasp or two left, but we’ve made it through, and change is on the way.

Prior to that, the models point to a shortwave moving through the upper Midwest next weekend. Will it have sufficient moisture and instability to work with near the warm front? Good question; we’ll find out, assuming subsequent model runs don’t wash it out. So far it has shown up consistently. For those of us who live northeast of Tornado Alley, it’s worth keeping an eye on.

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel.

My life in three steps: (1) Born at West Point, New York—so I knew I wanted to be a military guy. (2) Started playing the accordion at age eight—because my parents told me to. (3) Got interested in weather during high school—because it fascinated me. Putting the three all together, I went to Penn State for my meteorology degree while playing the “Rain, Rain Polka” at parties for extra income, and I graduated with an ROTC commission in the Air Force. After twenty-two years in the USAF Weather Service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel. color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.

color monitor, a dot-matrix printer, a second floppy disk drive, and more memory. And then, after some deliberation—about two seconds—I went all the way. I broke open my piggy bank and got my first harddrive. Six hundred dollars for a whopping 20 Mb—what a deal! I had now attained nirvana.