Every once in a while I like to feature a post by a guest blogger from the worlds of either storm chasing or jazz. Today let me introduce to you my buddy Neal Battaglia. Neal is a tenor man who maintains a wonderful blog on jazz saxophone called SaxStation.com. The site covers acres of territory of interest to saxophonists. If you’re not already familiar with it, then you owe it to yourself to check it out.

After contemplating the nature of my own site, with its odd blend of wild winds and woodwinds, Neal is here to share his thoughts in a post titled…

Saxophone and Storms

By Neal Battaglia, SaxStation.com

Initially, storms and saxophones seemed an odd combination to me.

On this site, I would read Bob’s posts on saxophone, but not always the ones about storms.

However, when I thought about it for a minute, a number of musicians enjoy nature and are inspired by it. And storms are some of the most extreme examples of nature.

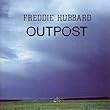

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.

One of my favorite trumpet players, Freddie Hubbard, had a record called “Outpost.” The cover shows a lone farmhouse out in a wide-open plain with a storm beginning to brew overhead. When you listen to the tracks, you really hear the movement of the storm–the lead-in to it, the calm in the middle, and the conditions afterward.

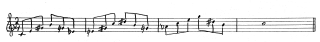

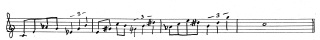

My all time favorite saxophone player, Stanley Turrentine, recorded an album called “Salt Song.” On it is a tune that I like a lot called “Storm.”

These two masters both took musical ideas from many places, reminding me that music is a reflection of our experiences. Your life comes out to be shared with the audience when you improvise on saxophone and write music.

In October of 2009, I took three planes across the country to Nashville and eventually arrived in the backwoods for a “music and nature” class. It was an awesome experience.

The guy in charge of that class recorded an album called “‘Thunder.”

Nature in general and storms specifically seem to act as a muse for musicians. They are something that we all experience (although possibly less if you’re an extreme city slicker). And music transcends language barriers. So you can feel storms by listening.