You’ve heard it repeated often over the years during tornado warnings: If a tornado approaches you while you’re driving, abandon your vehicle and seek shelter in a ditch. For several decades that instruction has been disseminated as if it were gospel truth. But is it a proven life-saver or, like, some other popular tornado safety myths (hide under an overpass, open the windows of your house, head for the southwest corner of the basement) bad advice that could get you hurt or killed?

In my opinion, it depends. While the National Weather Service has historically recommended the ditch, recently at least some weather stations have been modifying that advice, and a lot of experienced storm chasers disagree with it vehemently. Among the excellent reasons why they would prefer to take their chances in a vehicle rather than in a ditch, they cite the following:

◊ Flooding. A ditch is a poor escape option if it’s rapidly filling with water. There’s no point in surviving a tornado only to drown in a flash flood.

◊ Debris. All kinds of material can get pitched into a ditch with lethal force during a tornado. This is no idle concern; ditches regularly fill with tornado debris.

◊ Electrocution. There you are hiding in your nice, flooding ditch, and down comes a power line smack into the water. Fzzztttt! You’re a crispy critter.

◊ Snakes. Depending on where in the country you live, you could find yourself keeping company with rattlesnakes, copperheads, and water moccasins.

All of the above are reasons commonly given by chasers why they will never abandon their vehicles in favor of a ditch. I’ll add one of my own: Unless a ditch is sufficiently deep, chances are good that the wind will just scoop you right out of it and blow you away. Take a look at this photo of a rear-flank downdraft (a type of strong, straight-line wind from a severe thunderstorm) and note how the dust fills the shallow ditch on the right. The RFD jet was crossing the road about 100 feet in front of our car when I snapped the photo, and it was easy to see that the wind wasn’t merely blowing over the ditch–it was blowing into it. There’s no reason why tornado winds won’t do exactly the same thing, only a lot more intensely. (Note as well the rainwater in the ditch and the power lines hanging overhead.)

Still not convinced? Check out this up-close video of a small but intense tornado traveling along a roadside ditch in Minnesota and consider how you would have fared had you been taking shelter there.

And then there’s the obvious.

Why on earth would you want to abandon your best means of escaping the tornado altogether, not to mention the added protection your vehicle affords, in order to expose your soft, pink body fully to the elements?

Contrary to what you may believe, you can outmaneuver a tornado. Storm chasers do it all the time. Tornadoes move at roughly the same speed as their parent storm. True, some can rip along at 60 mph or more, particularly in the early spring. But most tornadoes move at a much slower rate, generally between 25-45 mph. Given a decent road grid, unless you’re in an an urban area where traffic is congested, or unless your view of the tornado is impeded by terrain or precipitation, your most commonsense survival tactic is to get out of harm’s way. If you can see a tornado, you should be able to escape it unless it is nearly on top of you.

How to outmaneuver a tornado: advice for the average Jane or Joe.

Those of you who are storm chasers can skip this section. You’re already quite familiar with approach and escape tactics, or at least, you should be. (Of course, you’re more than welcome to share your own wisdom in the comments section, and I hope you will.) The following is written for the saner 99.9 percent of the population who don’t go gallivanting across the vast American heartland in the hopes of encountering massive wind funnels filled with debris, but who would like to know what to do when they see one approaching while they’re out driving in their cars.

Let’s say you find yourself in just such a situation. Your most obvious first step is to determine whether the tornado is moving toward you. Chances are it will simply miss you. If you’re north of its path, you may want to park under a shelter, because if you’re not already getting clobbered by hail, you probably will be shortly. If you’re south of the tornado, you might want to head a little more south yet just to be on the safe side. Then pull of the road and enjoy the spectacle, because it’s not one you’ll see every day.

If the tornado is in fact heading your way–if it appears to be growing larger without apparently moving–then you need to take action. Assuming that it’s approaching from the west or southwest, as will be the case in most (though by no means all) situations, your best bet is to head south.

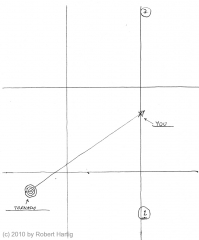

In the map to your right (click to enlarge), the tornado is moving northeast directly toward you. Note the location of the number 1. That’s the general direction you want to head in for reasons you can easily see. If south isn’t an immediate option, then drive east and bail south at your first opportunity. Depending on how near you are to the tornado as it passes north of you, you may get slammed with vicious straight-line winds wrapping in from the storm’s rear flank, but that’s better than getting munched by the tornado itself.

The overall point is to sidestep the tornado by moving at a right angle to its path. (Situation: You’re standing in the middle of a railroad track and a train is coming. What’s the smart thing to do? Answer: Right–step off the tracks!)

Heading north toward location 2 is also an option, but it’s one you’re better off avoiding if you can. While you’ll escape the tornado, you will very likely find yourself in the storm’s hail core. As a general rule, heading south will take you away from the big hail and blinding rain. Of course, if you think the tornado is likely to pass south of your location and you’re concerned about crossing its path, then use common sense and either stay where you are or else move north. Better to risk losing your windshield than your life.

Let’s say, though, that you’re in a worst-case scenario. There’s no fleeing. Many chasers, probably most, would still prefer to ride out a tornado in their vehicle rather than in a ditch. Granted, neither option is a good one. There’s no question that the more violent tornadoes can do horrible things to an automobile; pictures abound of cars and trucks crumpled into balls of metal, or wrapped around trees, or filled with lethal debris. But at least your vehicle provides a layer of protection that you wouldn’t have in a ditch.

So is a ditch ever a good option?

This is a good place to mention that the ideas shared in this article are my opinion. They are not the result of scientific research. Then again, neither is the decades-old advice to abandon your vehicle for a ditch. It started as someone’s reasonable-sounding idea that gained authority through repetition rather than actual proof. Still, it does make sense to get as low as possible during a tornado, and I personally think there are occasions when a ditch could offer viable protection.

It’s a matter of situational awareness. Is the ditch deep, deep enough that it could minimize your exposure to the wind? If it were me, that would be my first question. Assuming that the answer was yes, my next concern would be with my surroundings. I would feel much more hopeful about sheltering in a ditch in the open countryside, with little in the way of trees and other large debris to get chucked at me, than I would in an area full of structures all strung together with power lines. And what about vehicles? I would certainly want to get far enough away from my own car that it wouldn’t be likely to roll over on top of me.

Flash flooding? Snakes? Those issues are of greater concern in some parts of the country than others. The best I can say is, know the environmental hazards of your territory and make your choices accordingly.

Again, the best way to survive a tornado is to get out of its path. Since most tornadoes are only a few hundred feet wide, avoiding them in a vehicle is quite easy given decent visibility, good roads, and ample lead time. If you’re in your car and you spot a tornado approaching in the distance, don’t take the fatalistic view that you can’t outrun it. It’s probably not heading directly at you in the first place. Determine where it is heading and do what you need to in order to position yourself elsewhere.

However, if it appears to be growing larger without moving to either the right or left, then you need to either skedaddle or else find adequate shelter. Ditches rarely qualify. In most circumstances, you should consider a ditch as only a last-ditch option.