Tenor sax, soprano sax, trumpet, and clarinet players, I’ve kept my promise and haven’t forgotten you! I’m pleased to announce that The Giant Steps Scratch Pad, Bb Edition is now published and available for purchase on Lulu.com.

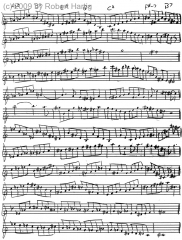

In case you haven’t followed any of my related posts, “The Giant Steps Scratch Pad” is a book of licks and patterns on the Giant Steps cycle. Made for the woodshed, it had its inception over ten years ago during a period in my life when I was immersing myself in Coltrane changes. Finding nothing in the way of practice material, I bought a spiral-bound book of staff paper and began writing down my own ideas, which multiplied over time into more material than I could wrap my arms around.

In recent months, it occurred to me that the material could benefit other jazz musicians. So I transcribed it using MuseScore, and after more hassles and delays than I care to describe, finally published the Eb edition for alto sax and baritone sax players just two weeks ago. Read the release notice for more information on what the book has to offer jazz instrumentalists of every stripe who want a practice companion to help them develop their technique for improvising on “Giant Steps.” In a nutshell, information abounds on the theory of Coltrane changes, but this is the first book I know of that actually gets you soloing on “Giant Steps.”

Flutists and other concert pitch instrumentalists, fear not: The C edition is next in line, and I’m already underway with editing. Bass players and trombonists, a bass clef edition will follow after the C edition has been published. So, campers, be patient. Nobody’s going to be excluded from the party.

“The Giant Steps Scratch Pad” is now priced at $10.95. I had initially settled on $13.95, but when I factored in the cost of shipping from Lulu, I decided to trim down by a few bucks. Head to the Scratch Pad landing page to access both the Eb and Bb editions, and other editions as they become available.

I’m hoping to have the C edition published within a week, so look for another announcement soon.