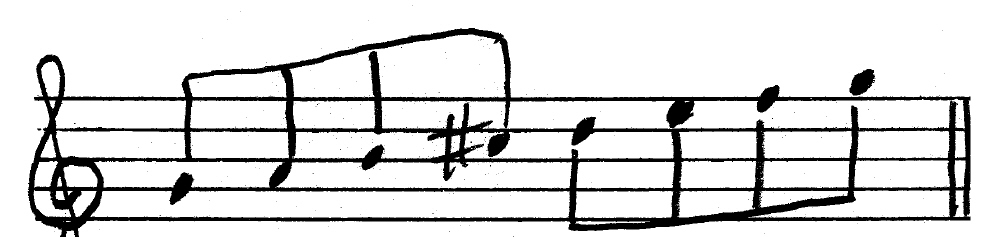

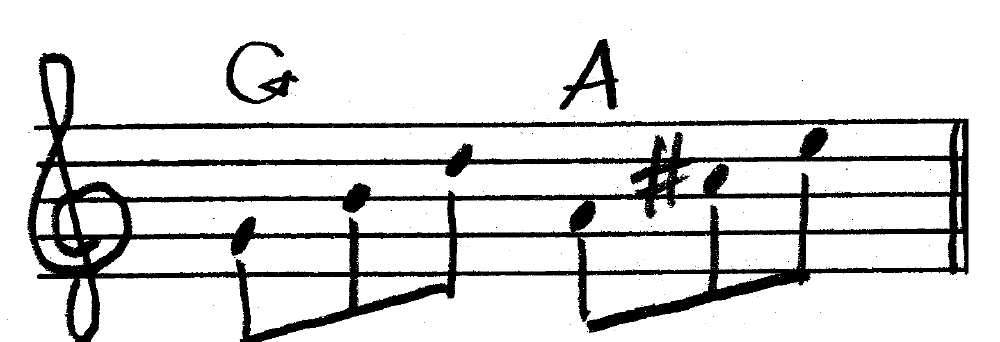

Excuse me while I deviate from this blog’s generally non-commercial tone into a bit of blatant self-promotion. As you know if you’ve followed the musical part of Stormhorn.com for any length of time, I’ve self-published a practice resource for jazz musicians titled The Giant Steps Scratch Pad. Without going into details that I’ve already covered on the Scratch Pad page, the original editions provide 155 licks and patterns in the standard key for concert pitch, Bb, Eb, and bass cleff instruments.

This new edition takes that effort to the ultimate level for those who want to master John Coltrane’s jazz rites-of-passage tune, “Giant Steps,” in every key. Available now as an instant PDF download,The Giant Steps Scratch Pad Complete gives you a grand total of 1,860 exercises written in treble clef.

Speaking modestly but plainly, this is a terrific resource for jazz musicians. It gives you enough theory to help you understand Coltrane changes in the context of “Giant Steps”; however, its focus is on getting you actually playing through the changes comfortably and creatively. To the best of my knowledge, no other book like it exists that provides a practical and comprehensive means of mastering “Giant Steps.”

Written in treble clef, The Giant Steps Scratch Pad Complete is 252 pages in length and costs $21.95. As I’ve already mentioned, it is currently available as a PDF download only. That seems to be what people prefer, and I’m reluctant to invest more time and effort preparing a print edition unless I know there’s a reasonable demand for one. I’d have to charge more to make it worth my while, and you’d have to pay for shipping on top of the purchase price.

However, given the size of this new, complete edition, there may be an interest in a print version, so let me know. Enough requests can make the difference. And I will say that the cover which I had professionally designed for the standard-key editions looks very sharp, better than most of what I’ve seen in music stores.

To place your order, or to learn more about The Giant Steps Scratch Pad and check out printable page samples, click here.

Also, if you like what you find, please tell your fellow musicians. Self-publishing means self-marketing, and the best way to accomplish that is through word-of-mouth. Nothing means more to other musicians–and to me, personally–than the recommendation of a colleague.

Thanks for your interest and for spreading the word!

–Bob