Lately I’ve been spending considerable practice time on pentatonic scales. So named because it has only five notes, the pentatonic is as basic a scale as you can get. Its fundamental use for jazz improvisers is to provide a down-homey sound that’s great for playing the blues and a lot of gospel and contemporary praise music. Lacking a major scale’s handle-with-care tension tones of the fourth and raised seventh, the pentatonic furnishes a steady supply of consonant notes that work with pretty much any diatonic chord. It’s hard to go wrong using a pentatonic scale!

But once you start exploring its more complex applications, the pentatonic scale becomes more demanding. It is used freely as a source for angularity and a tool for outside playing, and you have to work out its possibilities in the woodshed if you want to use them skillfully in performance.

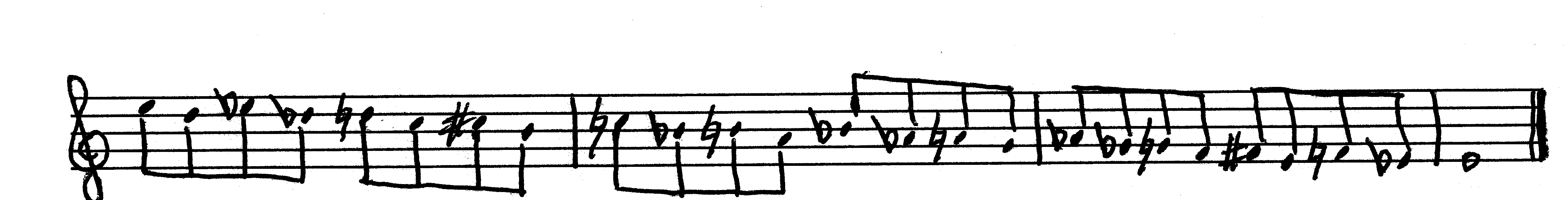

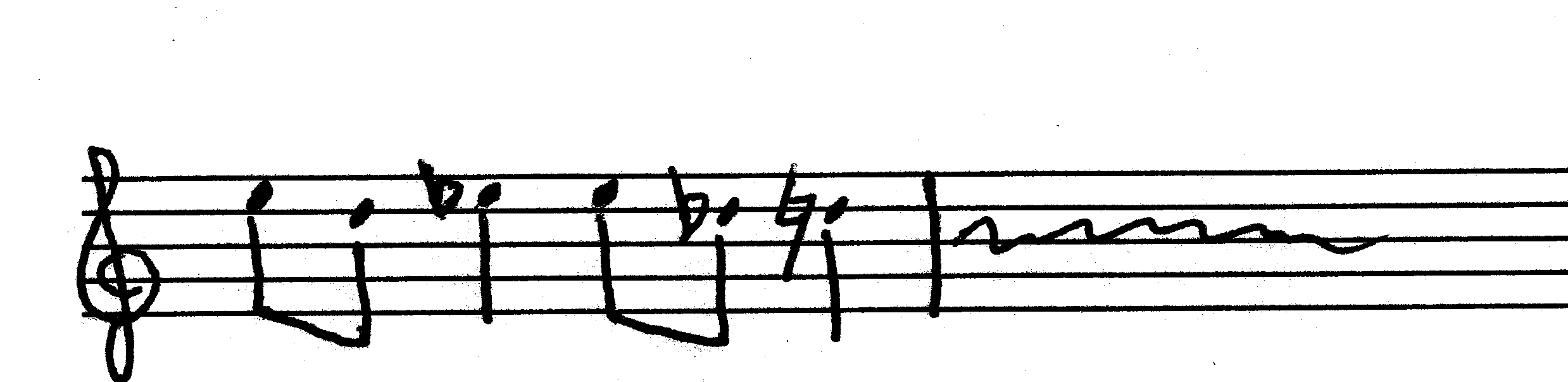

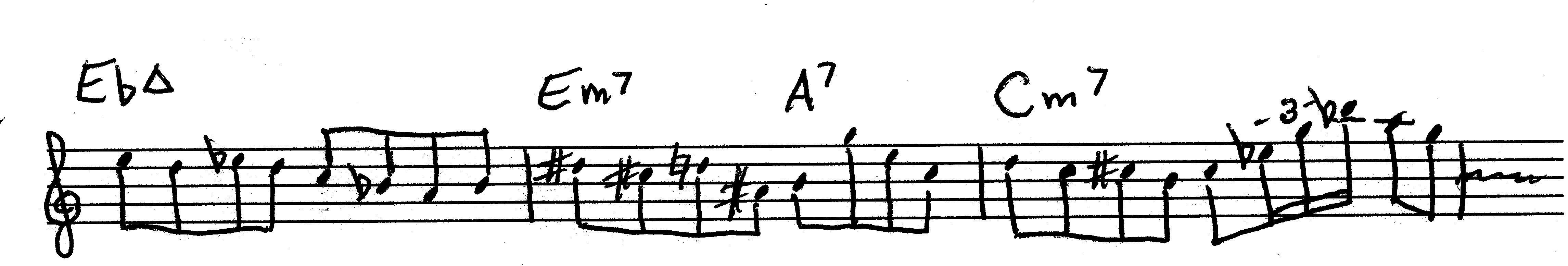

The two exercises shown here take the fourth mode of the pentatonic scale and move it by major third. This approach spotlights tone centers that divide the octave into three equal parts. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

The two exercises shown here take the fourth mode of the pentatonic scale and move it by major third. This approach spotlights tone centers that divide the octave into three equal parts. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

The exercises don’t lay easily under the fingers at first, but stick with them and you’ll soon be ripping through them with Breckerish velocity. Remember, the key is to memorize these patterns as quickly as possible so you don’t need to look at the written notes. Since each exercise takes you through three tonal centers, you’ll need to transpose the material by half-step three times in order to cover all twelve keys.

Get cracking–and have fun!

If you found this post helpful, visit my jazz page for more exercises, articles, and solo transcriptions.